The Early State of Israel and Jewish Culture

Early Israeli statehood balanced collectivist Zionist ideals with growing individualism and saw the emergence of a vibrant but conflicted national culture.

The postwar period in Jewish history saw an ongoing, creative, and fraught tension between dreams and reality, between a soaring Zionist narrative of idealism and the real challenges of building a new society. Tensions between veterans and immigrants, between religious and secular, and among different ethnic groups complicated the task of forging the new State of Israel.

On the one hand, this was a time of a powerful collectivist ethos shaped by Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion’s faith in the transformative power of the new Jewish state. Israeli leaders sought to harness the sacrifices of the War of Independence as they confronted the stark necessity of providing a shared identity to millions of newcomers, both survivors of the Holocaust and Jews from Arab lands.

On the other hand, this period witnessed a growing rebellion against this collectivist ethos, which expressed itself in many cultural arenas: in poetry and prose, in life writing and journalism, and in the arts. Writers examined the right to be different, to live a life apart from the collective. Essayists refused to accept pressures to reject two thousand years of Jewish diaspora history. Critics asked searching questions about how artists could create a distinctive Israeli culture that was both original and responsive to international trends.

All the while, Israelis from across the cultural spectrum had to examine the searing legacy of the Holocaust and how this inheritance affected the identity of the new state. In terms of sheer cultural creativity, these early years of statehood have few parallels in Jewish history. And while the rebirth of the Hebrew language had begun some decades before statehood, only now did it flower and develop as never before.

The Shaping of Israeli Political Identity

In 1944, at the height of the Holocaust, David Ben-Gurion, future prime minister of Israel, predicted that sovereignty—the experience of statehood—would create a new Jew, Hebrew-speaking and self-affirming, free of diaspora complexes, and able to defend him- or herself without sacrificing moral principles. This faith in mamlakhtiyut, literally “stateness,” defined Ben-Gurion’s political credo. To a great extent, post-1948 Israeli culture evolved as a dialogue with Ben-Gurion’s Zionist narrative and as a challenge thereto.

Few statesmen in Jewish history achieved as much as Ben-Gurion. His vision, his political will, his laserlike focus on the possible rather than the ideal played a decisive role in the founding of the State of Israel in 1948. Overcoming daunting challenges, and largely under Ben-Gurion’s leadership, Israel won its War of Independence, absorbed one million Jewish immigrants in ten years, and built a polity based, for the most part, on the rule of law.

Despite great difficulties, the young state doggedly created a shared sense of “Israeliness” based on the Hebrew language, a shared determination to defend the country, and the emergence of a vibrant popular culture in which music was especially important. At a time when many Jews had limited knowledge of Hebrew, music—more than literature or poetry—could appeal to both veteran Israelis and new immigrants. The popularity of army song troupes in the 1950s and 1960s and the widespread habit of public singing all encouraged a musical culture loosely known as Shirei Erets Yisrael (Songs of the Land of Israel). Besides universal themes of love and loss, these songs stressed patriotism, love of the land, memory of the war dead, and a deep-seated yearning for peace that belied any worship of militarism.

Ben-Gurion’s vision also had its limits, however. The state could not take the place of religion, dictate a uniform sense of history, or decree that collective needs take precedence over the individual and the private. Israel did not become the melting pot that Ben-Gurion had envisaged. Tensions festered between immigrants and veterans, between Jews from Europe and Jews from Africa and Asia, and between religious and secular Israelis.

Ironically, the spectacular victory of the 1967 Six Day War encouraged heady visions of total Jewish sovereignty in all of the “Land of Israel” and thus sparked the emergence of the very religious-messianic nationalism that Ben-Gurion had hoped to contain. While some leading Israeli writers supported a “Greater Land of Israel,” others, like the political activist Lova Eliav and the noted religious scientist Yeshayahu Leibowitz, warned that the fetishization of land and power would endanger the future of the state. Other warnings about the perils of victory and militarism came from the playwright Hanoch Levin, who, in works such as You, Me and the Next War and Ketchup, subjected the triumphalist pieties of post-1967 Israel to withering and controversial criticism.

Religion and Statehood

The fraught question of religion in the new state surfaced with the May 1948 “Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel,” which included the ambiguous phrase “Rock of Israel” to please staunch secularists leery of mentioning God. Such deep disagreements explained why the young state deferred the drafting of a written constitution. Another source of tension in the new state derived from deep-seated Zionist contempt for the diaspora. Ben-Gurion saw the establishment of the state as a decisive break with the diaspora and its history; for the first time since the Roman destruction of the Second Temple, Jews had regained their agency and could make their own history. In this spirit of negation of the diaspora, Ben-Gurion urged all army officers to Hebraize their names. Others went even further. In “An Epistle to Hebrew Youth,” written in 1943, the poet Yonatan Ratosh appealed to young “Hebrews” to “remove the Jewish cobwebs from their eyes” and become “Canaanites,” linked to the Arab peoples of the Middle East rather than to world Jewry. But other writers, like Chaim Hazaz, pointedly reminded Ben-Gurion that the diaspora legacy of tradition and respect for learning had forged the Jewish people. What good would the state be, Hazaz asked, if it caused Jews to forget who they were? “We have ceased to be a nation,” Hazaz complained to Ben-Gurion. “We have become a state.”

The Sabra Generation

In the early years of sovereignty the cult of the “Sabra” loomed especially large. This proud first generation of native-born Hebrew speakers, self-reliant, irreverent, brusque, hardworking, with names like Uzi and Dani, saw itself as the stark opposite of the diaspora Jew. Many were proud members of the Palmach, the elite fighting force of Jewish Palestine. The songs around the campfire, the slang, the tall stories (chizbatim), all created a sense of belonging to a special group with a new culture and language. But writers such as Amos Kenan also discerned less attractive sides to the Sabra ethos, such as excessive dependence on the group and a corresponding lack of individuality.

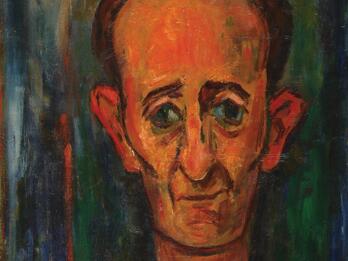

The terrible crucible of the War of Independence took a heavy toll on the first Sabra generation, poignantly described by such writers as Menahem Shemi. As the new state found its bearings, the memorialization of the fallen played an outsized role in an emerging Israeli culture. Mordechai Ardon’s For the Fallen, Batia Lichansky’s Holocaust and Rebirth, and Itzhak Danziger’s War Memorial were landmarks in Israeli painting and sculpture. Moshe Dayan wrote an iconic eulogy in memory of Roi Rotberg, a young member of Kibbutz Nahal Oz, who was killed by Arab infiltrators in April 1956. What made this eulogy so significant was Dayan’s brilliant evocation of empathy for the Palestinian plight in order to legitimize the Zionist cause and imbue Israelis with a determination to defend the state. Precisely because Arab hatred was so understandable, it was therefore implacable. Jews could not let their guard down, feel guilty about defending their homeland, or give in to tempting delusions about imminent peace. But some young Israeli soldiers who fought in the 1967 Six Day War, interviewed by Amos Oz, expressed the very doubts and guilt feelings that Dayan had warned against. They gave voice to their forebodings that a more terrible war was on the way. Some worried that victory had only embittered the Arabs while threatening to turn Jews into brutal occupiers.

In time, the challenge of sovereignty forced a reappraisal of many fundamental mainstays of early Israeli culture. The collective ethos of the cult of the Sabra, of the old Palmach and of mamlakhtiyut, confronted growing demands for privacy and individual space, even as mass immigration turned the veterans of the old Yishuv into a small minority. Ingrained rejection of the diaspora could not withstand the unrelenting intrusion of Jewish history and memory: the Eichmann trial—which had a transformative impact on previously negative and even contemptuous attitudes toward survivors—or the trauma of Israel’s isolation in the frightening weeks that preceded the 1967 war. In his 1971 book Israelis: Founders and Sons, Amos Elon shrewdly dissected the Jewish fear, and even neurosis, that lurked beneath Sabra bravado.

Immigration and Israeli Statehood

The “challenge of sovereignty” struggled to absorb masses of immigrants. Some Ashkenazic veterans, such as the journalist Aryeh Gelblum, felt disdain for “backward” Jewish immigrants from the Arab lands, especially Morocco, and questioned whether the bedrock Zionist commitment to open immigration really made sense. Newly arrived Jews from Iraq, Yemen, and North Africa quickly began to resent their treatment. Salman Shina’s From Babylonia to Zion conveyed the anger felt by a cultured Baghdadi Jew toward bureaucrats totally ignorant of the great achievements and traditions of Iraqi Jewry. Others lashed out at an official policy that sought to “civilize” non-European Jews instead of seeing them as equal partners in the building of a new culture. Yehuda Nini, in “Thoughts on the Third Destruction,” saw the humiliating treatment of Yemenite Jews as an ominous sign of Zionist decay, a loss of such fundamental values as appreciation for manual labor and basic egalitarianism.

But while these tensions between Ashkenazim and non-Ashkenazim led to deep scars and occasional outbreaks of violence, in the end they did not seriously threaten the integrity of the state, largely because of important countervailing trends. For all its faults, Israel was a functioning democracy, and aggrieved immigrants slowly learned how to work the system. There was also the common Arab enemy; many Jews from Arab lands felt pride in the Jewish state and its military successes. In turn, the elites and Ashkenazic Jews understood that the best guarantee of long-term survival was Jewish numbers.

Jewish writers from the Arab countries, mainly Iraq, also began to make their mark on Israeli literature as they explored the traumatic experience of displacement, the searing loss of language and status, the pain of discrimination, and at the same time, a determination to master Hebrew and to find a foothold in the Jewish state. Sami Michael’s “The Artist and the Falafel,” originally written in Arabic, drew a picture of poverty and displacement, of insensitive crowds who see in a poor young street artist as nothing but a source of entertainment and diversion. A turning point in modern Israeli fiction was the appearance in 1962 of Shlomo Kalo’s “The Pile,” a modernist portrayal of desperate Mizrahi immigrants seeking a demeaning and low-paid city job clearing a garbage heap. The same theme of social protest appears in Shimon Ballas’s “The Ma‘abarah” (The Immigrant Transit Camp), where immigrants from Arab lands express their bitterness at Ashkenazic condescension and vainly look for way to organize and fight back.