The Aftermath of the Holocaust in Israeli Culture

Israelis struggled to integrate Holocaust memory into national identity, as survivor literature challenged a preference for heroic resistance narratives.

Jewish Culture Faces the Holocaust

On both sides of the Atlantic, Jewish thinkers, culturally identified as well as assimilated, struggled to address the meaning of the Holocaust and whether it should be seen primarily as a crime against Jews or as a crime against humanity. René Cassin drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; Raphael Lemkin coined the term genocide. It was for the crime of genocide, rather than for the killing of Jews per se, that Hannah Arendt believed Israel should have tried Eichmann. By the same token, key Jewish organizations such as the American Jewish Committee funded social science research into the origins and causes of prejudice in an effort to show that antisemitism was not just a Jewish problem but a lurking cancer that threatened all healthy democratic societies. European-educated American rabbis harnessed the memory of the Holocaust to remind Jews of their obligation to support African Americans in their struggle for civil rights.

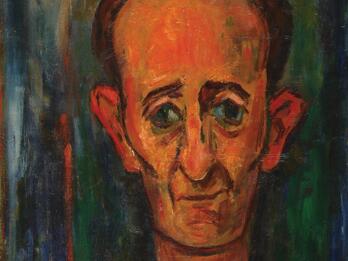

The first significant confrontation of Hebrew literature with the theme of the Holocaust was the 1951 publication of Uri Zvi Greenberg’s collection of poems Streets of the River, the only volume of Holocaust verse to achieve near-liturgical status. Greenberg, a vociferous opponent of the left-wing labor Zionist establishment, also defied its mandate to highlight Jewish heroism and resistance. Instead, he tore open the raw emotional wounds and guilt of Jews who had enjoyed the safety of the Yishuv while their families were murdered, even as he defied the political correctness of the socialist left by cursing the entire gentile world for its betrayal.

In a cycle of poems addressed “To God in Europe,” Greenberg depicts a drastically diminished God, a shepherd without a flock. In a godless, Jew-less world, it is left to the “lying poet” to rage, to mourn, to prophesy the coming redemption of Israel. “Where are there instances of catastrophe / like this that we have suffered at their hands?” asks the poet. “There are none,” he replies, “no other instances.” This annihilation is without analogy.

Aside from Greenberg, Hebrew literature in those early years paid relatively little attention to the Holocaust. There were many reasons for this. Holocaust survivors like the poets Abba Kovner and Dan Pagis were few and far between. The younger generation of Hebrew writers had not grown up in Europe, and their formative personal experiences had left them unprepared to write about the disaster. Yiddish writings did not excite much interest among Hebrew readers. For many Sabras, the Holocaust and its survivors were a foreign world, to be approached with caution and even involuntary feelings of disgust. And confrontation with Jewish survivors evoked more guilt-ridden ambivalence, explored in such works as Hanoch Bartov’s The Brigade.

By the late 1950s, new writers appeared on the Israeli literary scene who were themselves survivors. Uri Orlev, a child survivor of the Warsaw ghetto, went on to become one of Israel’s most celebrated children’s writers. His 1958 The Lead Soldiers, about children hiding in Warsaw, narrated from the perspective of a young child, reached a wide audience of Israeli readers, especially young people. Another survivor, Aharon Appelfeld, dealt with those events through a strategy of indirection and through haunting, almost timeless tales of exile and return. Against the backdrop of national rebirth, survivors lived their private lives and wrestled with their private demons, in private spaces untouched and unnoticed.

Literature and the Israeli War of Independence

Israel’s War of Independence—which began in 1947 and continued until 1949—inspired a literature that highlighted the triumphs and the pitfalls of the battle for Jewish sovereignty. The theme of the “living dead” became ever more salient as two years of vicious fighting decimated an entire generation, especially the soldiers of the elite Palmach. All Israeli writers in the first years of independence were haunted by the deaths of family members and close friends.

The existential danger faced by the Yishuv in its fight for independence underscored the priority of the collective; everything else—individual need, private concerns—was secondary. Poems such as Haim Gouri’s 1948 “Behold, Our Bodies Are Laid Out,” written after thirty-five Palmach soldiers were killed trying to relieve a besieged settlement, conveyed the emotional toll of the ceaseless fighting even as it underscored the just cause for which the soldiers fell and the absolute necessity of victory. Gouri also composed what would become one of the most memorable songs of the War of Independence, “The Song of Friendship.” S. Yizhar’s “The Prisoner,” written that same year, focused on the inherent tension between the just battle to win independence and the serious threat of moral degradation that caused Jews to mistreat a helpless Arab man. Few works written during the war made a greater impact than Moshe Shamir’s 1948 He Walked through the Fields, a gripping story of conflict between the personal and the collective. Written in the colloquial Hebrew of the new Yishuv, He Walked through the Fields was Israel’s first bestseller.

When the war ended in 1949, an inevitable emotional letdown followed. The return to civilian life, the disparity between the dreams of independence and the disappointments and failures of a new state, austerity and rationing, the enormous challenge of a mass immigration that threatened to inundate the old Yishuv, all contributed to a sense of depression and disillusionment. The guiding spirit of heroic sacrifice and stoic bereavement was questioned in such short stories as Yehudit Hendel’s 1950 “A Common Grave.” In 1954, Nissim Aloni’s popular play, Most Cruel of All the Kings, depicting the succession struggle for King Solomon’s throne, raised pointed and timely questions about the tendency of political power to corrupt leaders and to distort formerly lofty ideals.

In 1966, Amalia Kahana-Carmon, who would become one of Israel’s major stylists, published one of her first stories, “The Glass Bell.” In remarkable prose, which often followed the stream of consciousness of mostly women protagonists, Kahana-Carmon helped open up new vistas in Israeli literature: emotional fragility, the toll of memory and failed choices, the tension between social expectations and individual happiness. In a 1973 essay, “What Did the War of Independence Do to Its Writers?” Kahana-Carmon offered an intriguing insight into what she regarded as the potential pitfalls that faced Israeli literature. The generation of writers of that heroic era, she asserted, were good writers not because of the war, but despite it. For her, constant danger and existential vulnerability do not necessarily encourage good writing.