Art and Literature in the Postwar Period

Israeli art and literature reflected the emergence of a distinctive indigenous culture and moved from collectivist Zionist narratives toward individualism.

The challenge of sovereignty in the early years of statehood encouraged a far-reaching attempt to define what constituted a distinct, indigenous, Israeli culture. To what degree should Israeli painters, musicians, and writers look to foreign models, if at all? If so, should they turn to Europe? The Middle East? The legacy of the Jewish past? Or was it possible to transcend these models entirely?

Zionism and Israeli Literature in the Postwar Period

During the war years, the creative tension between Hebrew literature and the Zionist narrative, which would emerge in full force after 1948, dominated key writings, brilliant and disturbing reminders that Zionism was riddled with puzzles and contradictions, and that it was precisely literature, with its ability to delve into the world of individual emotions and imagination, that could offer insights lacking in the monochrome language of political cant. Wartime stories by S. Y. Agnon and Chaim Hazaz confronted many sensitive questions. Hazaz’s “The Sermon” challenged readers to understand how Zionism could offer salvation when it seemed to deny much of Jewish history. In “From Foe to Friend,” Agnon’s readers had to ask how Jews could fight off the Arabs and the British in the long run. Agnon’s novel Only Yesterday rested on the fraught paradox of Zionist promise in a land where so many Jewish immigrants found failure and heartbreak. Yet in the end, what mattered was that somehow the Zionist project went forward, despite setbacks and even when Zionism seemed to defy logic and common sense. There was little triumphalism in these wartime stories by Agnon and Hazaz, who sensed the great struggle that loomed in the future. But the fact that they wrote in Hebrew, and lived in a Hebrew-speaking Yishuv, offered a vision of a house that might finally endure.

The establishment of a Jewish state in 1948 presented Hebrew writers with great challenges but also with great opportunities. After 1948, the ongoing, critical dialogue between Hebrew literature and the Zionist narrative would proceed in a new register and reflect an interplay of parallel generations of writers: an older generation (Agnon, Alterman, Goldberg, Greenberg, Hazaz) at the peak of its powers, the first generation of native Hebrew speakers (Bartov, Gouri, Kaniuk, Megged, Shamir), new immigrants from Europe and the Arab lands (Appelfeld, Ballas, Pagis, Kovner, Kalo, Michael), and finally the “generation of the State,” writers like Amos Oz and A. B. Yehoshua whose formative experience had been not the battle for independence but the early years of statehood. This literature confronted the same problems addressed in life writing and political thought: the tension between the collective and the individual, the fraught relationship between Zionism and the Jewish past, the impact of mass immigration on a society that had privileged the myth of a Sabra elite, the changing nature of the Hebrew language, and finally, the difficult theme of the Holocaust.

In the 1950s a reaction set in against the collectivist, Zionist ethos as a new search began for a fiction and poetry that would evoke the individual and private sphere. Poets like Natan Zach declared that poetry should eschew exalted language and collective bombast for a new personal voice. This yearning for private space was also reflected in Pinḥas Sadeh’s irreverent 1958 autobiography, Life as a Parable, and in Yehuda Amichai’s 1961 Love in Reverse. Dahlia Ravikovitch’s landmark poem “Clockwork Doll” explored how a woman was caught in a trap shaped by men’s expectations and demands. In one of his Jerusalem poems, “Tourists,” Yehuda Amichai mused about a new kind of Zionism that eschewed national pathos even as it embraced the quotidian pleasures of everyday routines in the homeland.

Israeli Statehood and the Arts

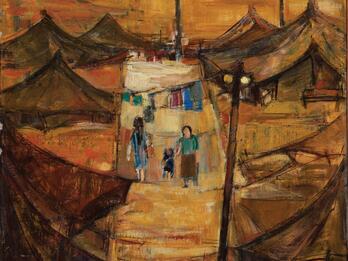

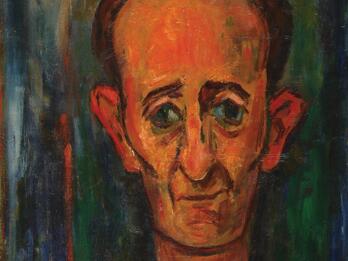

In 1953, the Israeli conductor, composer, and music critic Alexander Uriah Boskowicz wrote a revealing article, “The Problems of Native Music in Israel,” which called on Israeli composers to avoid aping easily available European or Arab traditions and craft instead a distinct Israeli music inspired by the Mediterranean milieu, the landscape of the land of Israel, the Bible, and the very sounds of the Hebrew language. Four years later, Ḥaim Gamzu, a leader of the Israeli art world and a director of the Tel Aviv Museum, declared that Israeli artists and sculptors had successfully begun to fashion their own original and distinctive style. The new experience of sovereignty had helped create new tastes and sensibilities. The culture of memorialization played an especially important role in encouraging a specifically Israeli “public sculpture” that forged a bond between the artists and the wider public.

Many Israeli artists, such as Yosef Zaritsky, Marcel Janco, and Mordechai Ardon, felt a natural tension between a search for the contours of a distinct original and Israeli culture and a determination to gain wider recognition in the international art world. But these years saw ongoing experiments that, even as they embraced biblical themes and local landscapes, stood out for their originality and creativity. No less important was the work of Israeli photographers like David Rubinger, who documented the struggles and achievements of the young state. His 1967 photo of Israeli paratroopers at the Western Wall in Jerusalem acquired iconic status and transformed the image of Jews in public perception throughout the West.

Scholarship and Literature after Statehood

Jewish scholarship in Israel also began to find its own distinct voice. As early as 1944, Gershom Scholem called for a fresh turn in Jewish studies that underscored a new relationship between Jewish scholarship and the rebirth of Jewish sovereignty. The apologetic scholarship of the diaspora, Scholem emphasized, had dictated outworn agendas that should give way to an unencumbered awareness of a living Jewish people and of the diverse and often overlooked strains of Jewish cultural development, including mystical and messianic movements and folk culture.

Meanwhile critics and essayists worked their way toward an understanding of an evolving Israeli literature that engaged the growing complexity of Israeli society. The influential critic Barukh Kurzweil lambasted both secular Zionism, which he saw as culturally sterile, and Scholem’s heterodox denial of a normative, integral Jewish cultural tradition. In his 1950 critique of S. Y. Agnon’s A Guest for the Night, Kurzweil saw Agnon as a literary model for the Israeli literature of the future, liberated from false nostalgia for a failed diaspora but still firmly anchored in Jewish tradition. He compared the author’s return to his Polish town to Odysseus’ return to Ithaca, a masterly evocation of a “before,” of a lost past.

While Kurzweil measured Israeli literature by the yardstick of an integral Jewish culture, other critics saw Israeli culture as a frenzied work in progress where few of the younger writers possessed the firm grounding in Jewish texts that had marked older authors like Hazaz or Agnon. The very newness of Israel, the breakneck pace at which an unformed society was emerging from the many corners of the diaspora, put a priori constraints on Israeli literature that writers from other nations did not have to face.

The Israeli literature of the future, the prominent Israeli writer Amos Oz pointed out, would be created by writers watching a new society take shape at warp speed. “This is a world without shade, without cellars or attics, without a real sense of time sequence. And the language itself is half-solid rock and half-shifting sands,” he wrote. “We had folk songs before we had a folk.”

By 1939, Hebrew literature in the “free zone” was largely safe; it had completed its migration from Eastern Europe to the land of Israel. The wartime Yishuv was torn by powerful crosscurrents and paradoxes: on the one hand, wartime prosperity and the growing self-confidence of the new Hebrew-speaking youth, on the other hand, guilt and anguish caused by news of the murder of European Jewry. Nathan Alterman’s 1940 poem “The Mole” evoked the power of the living dead, whose constant presence shaped Jewish memory and held the living in a firm, endless grip. This presence would frame one of the iconic poems of modern Hebrew literature, Alterman’s ambiguous “Silver Platter,” written in 1947 on the eve of Israel’s War of Independence. This poem, which entered Israel’s secular liturgy, evoked a gathered, expectant nation confronting two young, exhausted Jews, a young man and a young woman, whose sacrifice would be the unending price that Jews would have to pay for the state.