Theater in Jewish Culture

The novelty in Jewish performing arts in the later eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries involved the adaptation of traditional materials into new forms, as well as a turn to performing arts that were unconnected to religious life.

The ritual cycle of Jewish life had always contained a performative aspect. The Passover Seder provided a dramatic ritual around the family table while everyone told the Exodus story, sipped wine, dunked herbs, and counted off the ten plagues. The Torah was read weekly in public with precise cantillation, and cantors led prayer services in joyful or mournful tunes as the occasion demanded. Purim set the scene for carnival-style revelry, costumed antics, and a purim-shpil (Purim play) capping the merriment of that day. These traditional channels of the performance of Jewishness continued into the modern period, often with some alterations.

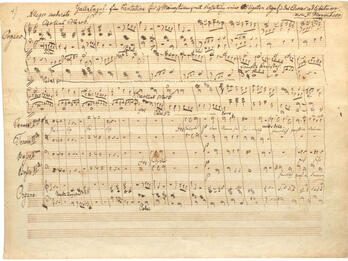

The novelty in Jewish performing arts in the later eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries involved the adaptation of traditional materials into new forms, as well as a turn to performing arts that were unconnected to religious life. Jews flocked to theaters and became ardent subscribers, performers, and producers of plays, operas, and music. Some of the most renowned libretti and music of nineteenth-century opera were composed by Jews; some were prolific writers of operettas. Every manner of support for the performing arts could be found within the Jewish world. Jews made their mark as creators and consumers of world-class art music. Remarkably, many artists made a transition within a generation or two from plying their skills within the traditional Jewish ambit to playing them on the greatest stages in the world.

The pathbreaking turn in this period lies in the Jewish entry into artistic spheres previously considered beyond Jews’ abilities, “belonging” instead to European social strata where Jews were not welcome. Like many other elite arts, music, opera, and theater required special training, lifelong exposure and appreciation, cultivated patrons, and appropriate performance settings. The business of what we call today “classical music,” “classical opera,” and professional theater changed dramatically in the eighteenth century. In this period, it stepped away from its ecclesiastical roots and was reinvented as public entertainment. Such innovation created spaces that had hitherto been closed to Jews.

This entrepreneurial spirit was evident on all types of public stages. Theaters presented plays written by Jews, featuring Jewish characters, or acted by Jewish professionals. Rachel Félix maintained classical tragedy on the French stage as a singular presence against the prevailing trend of romantic comedy, and Sarah Bernhardt achieved her early international acclaim on the stage in this period. The first Arabic-language secular script for a play, written by Abraham Daninos, was published in the mid-nineteenth century.