Music and Opera in Jewish Culture

One of the most striking changes in European Jewish culture toward the later eighteenth century was marked by the entry of Jews into art music, opera houses, and the stage.

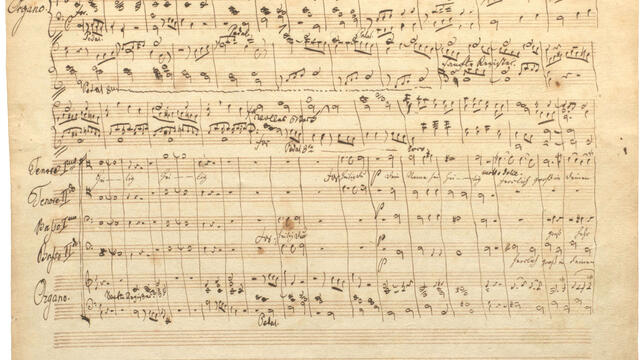

Jews had always cherished lofty liturgical traditions, and popular occasions for musical and theatrical expression abounded. Torah cantillation and cantorial tunes that dated to medieval times continued in synagogue tradition. In the early modern period, many synagogues supported a musical team, with cantor, bass, and meshorer (voice accompanist) harmonizing the music. Weddings, purim-shpils, and the dramatization of Bible stories provided entertainment over the centuries. One of the most striking changes in European Jewish culture toward the later eighteenth century was marked by the entry of Jews into art music, opera houses, and the stage.

Conservatories of music established neutral standards for judging talent, opening their doors to those without social connections. Technical innovations in instruments and acoustics enabled music and voices that had been played in small spaces to be projected powerfully to large audiences in grand halls. Instead of being sponsored by churches, royals, or small elite circles, patronage of artistic performance expanded to public “audiences,” and this required an entirely new economic model for the giant productions.

Once the doors began to open, music by Jews ceased to be “Jewish music.” It entered and belonged to the broader world. In some cases, the Jewish (or born Jewish) composers bridged both worlds, but the Posen Library includes all manner of musical creation by Jews without distinguishing whether the form and content overtly indicate Jewishness. The role of Jews as critics, journalists, and printers of music and of librettos contributed immeasurably to its popularization as one of the accoutrements for accomplished educated citizens.

The first half of the nineteenth century saw the breakthrough of Jewish composers and performers to the greatest renown on the European stage. In the 1830s and 1940s, Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy, Fromental Halévy, and Giacomo Meyerbeer, each with strong ties to his Jewish origins, were the most celebrated composers in France and in German lands and were renowned throughout Europe. Jews brought aspects of Jewish synagogue music into the larger world of classical music, while progressive synagogues took contemporaneous Western music into their services. Cantors began to collect and transcribe arrangements of synagogue music, and many introduced Western elements into their arrangements. In the late nineteenth century, professional Yiddish theater and opera matured in Eastern Europe and opened a new chapter in modern Yiddish culture.

Jews stood at the forefront of a movement to integrate “indigenous” music into the Western canon. Mordechai Rosenthal (Ròszavölgyi) advanced the cause of “gypsy” music in Hungary, and British composer Isaac Nathan championed Australian aboriginal music later in his life. Joseph Gusikov of Shklov enthralled Jewish and non-Jewish audiences with ingenious devices on which he played a form of klezmer folk music while dressed in Hasidic garb. The integration of traditional elements of Jewish folk music and theater into performances intended for modern audiences symbolizes the journey of Jewish performing arts that had come full circle.