Material Culture and Modernity

Discover the many types of objects—furnishings and clothing, jewels and medals, wares—crafted by Jews or specifically for use by Jews.

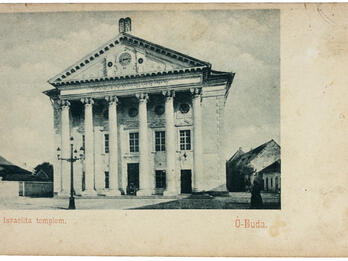

Borrowed from the fields of anthropology and ethnography, the term material culture signifies objects and built physical environments that tell us how people navigated, related to, or shaped their material world. Many types of objects—furnishings and clothing, jewels and medals, wares crafted by Jews or specifically for use by Jews—are included in the Posen Library.

“In portraying patterns of life in the modern period, changes in the ways Jews lived privately and publicly, their dress, manners, social customs and behavior, physical possessions and space and their attitudes to them, need to be integrated. For wherever Jews lived they possessed objects, and . . . those from the modern period are many, bearing the stamp of a Jew’s identity, relationship to the outside world, and sense of self.”1

There are precious few material objects shaped by human hands that do not convey the character of the individual creator as well as that of the larger society and culture in which it was made. A humble spoon, a chair, an item of clothing—each can be made of many materials, in so many patterns and shapes. As universal as they might appear to be, each exemplar is unique in the age before mass production. In addition to many single objects, we have tried to convey a sense of the material surroundings of Jewish spaces. When objects or environments proved impossible to include in our collection, we have relied on the “next best thing.” An inventory of household goods from Jews in colonial America, although technically a text, gives a sense of the material possessions considered significant in their time and place. The delicate watercolor of Fanny Hensel’s music room likewise allows us to perceive the furnishings and sensibility of the physical space in which her music composition and private rehearsals took place.

Ritual objects constitute one of the enduring platforms for Jewish artistic creativity and patronage through the ages. Each piece manifests its creator’s responsibility to the purpose of the object and its prescribed forms, alongside the desire to transcend its physical limitations and create an artifact of surpassing meaning. Ritual objects have one of the longest trails in Jewish art history. Indeed, in the not-too-recent past the very term Jewish art would conjure silver Kiddush cups and Havdalah spice boxes, Seder plates and illuminated manuscript Haggadahs. Artisans worked from the most precious to the most base of materials, from refined gold and silver to wood and paper. They created ritually necessary items, such as menorahs, as well as decorative objects, such as mizraḥ and shiviti signs, each invested with individual beauty, yet reflecting the larger culture of the time. Mizraḥ (east) designated the wall in the house that faced east, whereas shiviti was the starting word of the verse “I place God before me always” (Psalm 16:8). Neither of these signs was ritually obligatory in any way. They migrated from synagogue walls, where they served to concentrate worshipers’ attention, to broadsheet pages, to home decorations, marking spaces as Jewish abodes.

It is worth pausing to note that depending on Jewish political status in a given time and place, the craftsmen and artisans may or may not have been Jews. In many Muslim lands in the nineteenth century, metalworkers were Jews because Muslims were forbidden to engage in the craft. In Poland, the Czech lands, and later Russia, Jews often organized themselves into craft guilds that played an important social and economic role. In Western Europe, through the first part of the nineteenth century, Jews were excluded from guilds and often commissioned Christians to create ritual pieces in silver to their specifications. In colonial America, by contrast, Jews were free to choose to work in silver, as Myer Myers’s works attest. Beyond political status, each work exemplifies the interplay between local artistic traditions, Jewish customs and requirements, the economic status of the parties, and of course individual artistic imaginations and abilities. Many items in the Posen Library were used and beloved even by Jews whose attachment to religious tradition was marginal at best. The ritual objects can be divided into two types: objects that were used to mark life-cycle events in a Jewish key and objects that were used in ritual tied to the Jewish calendar.

Life-Cycle Rites and Objects

For every stage of life from birth to death, for every life-cycle ritual, the embellished artifacts speak to the values their makers held dear. Jews all over the world sought every protection for children yet to be born and for newborns by invoking angelic names on amulets and ordering evil spirits, often embodied in the name Lilith, to stay away. Some amulets designated a specific child to be the beneficiary of special protection. Since the biblical period, circumcision was practiced to represent the covenant between God and male Jews. Special seats, often beautifully decorated, were set aside at circumcision ceremonies for the invisible presence of Elijah. Special implements to care for the infant and adornments were created to commemorate the event. In Ashkenazic communities, mothers would embroider a cloth sash (wimple) with the new baby boy’s name and blessings for the future. When he was old enough to attend synagogue, he ceremonially brought the sash to serve as a Torah binder. The sermon for the bar mitzvah child coming of age cannot be captured by an object, but as photography grew in popularity, pictures of the bar mitzvah boy marked this rite of passage.

Marriages were celebrated with greater embellishment than any other life-cycle ritual. During his sojourn in Tangier, Morocco, the French painter Eugène Delacroix was moved by the way a Jewish mother lovingly prepared her daughter for marriage. His painting Saada, the Wife of Abraham Ben-Chimol and Préciada, One of Their Daughters (1832) immortalized the moment and captures a larger sense of the interior space as background for the rich life that unfolded within it.

The end of life’s journey, too, was invested with dignified ritual. Jewish shrouds and coffins were to be plain, as the soul journeyed into a world where wealth and material matters fell away. But the “holy society (ḥevra kadisha)", members of the community who attended to the dead and prepared them for burial, marked their work with lasting images. Even the implements they used to prepare the dead were specially marked. Finally, while poor and rural Jews could not always afford lasting markers, many Jews were able to set carved and engraved headstones that served as durable memorials to the departed. These became and remained platforms for artistic creativity, with traditional signs indicating priestly or Levite birth or the person’s occupation.

Ritual Objects Tied to the Jewish Calendar

The second category of ritual objects consists of those whose primary purpose was to carry out religious ritual related to the Jewish calendar, governed by a long tradition of hidur mitsvah, carrying out a religious ritual in the most beautiful manner. These objects spanned the gamut from humble to exquisite. They were used on Sabbath and holidays, some designed for private domestic use and others intended for the synagogue.

As has been practiced through the ages, every married woman blessed the Sabbath on special candlesticks or hanging lamps, the Sabbath day sanctified by a blessing over wine and special challah loaves presented on platters. The New Year included honey dishes to symbolize sweetness and the blowing of the shofar (ram’s horn) in the synagogue. Its plaintive notes would arouse the congregation to introspection and penitence. The sukkah (tabernacle) brought Jews outdoors into temporary shelters that reminded them of the transience of the material structures in their lives, evoking the tradition of their desert sojourn when clouds and fire were their only protection. Jews built architecturally innovative sukkahs and decorated them to be as inviting as possible. Hanukkah brought lamps in many different materials and an astonishing profusion of decorative styles. The lamps were supposed to be seen by the public as reminders of the miracle of light against the forces of darkness. The daily prayer book, special prayer books for holidays, along with the Scroll of Esther and various accoutrements for Purim provided additional opportunities for lively illustration.

Passover was the high point of the ceremonial year, and the Haggadah, its text the foundation story of the Jewish people, the story of the exodus from Egypt, was one of the most beloved, adapted, commented-on, and decorated Jewish books. Over the centuries its style and illustration reflected the Jewish historical experience. The Seder plate, matzo covers, pitcher and basin for ceremonial washing of hands—indeed, every aspect of the Seder—was fair game for artistic embellishment.

The adornments inside synagogues, from the Torah vessels to charity boxes, the Ark and its hangings, the gates and the walls, all provided opportunities for Jews to affirm, “This is my God and I will beautify Him” (Exodus 15:2). Because they protect and adorn the most sacred object in Jewish religious life, the Torah scroll, Jews created a rich array of accoutrements in the finest materials and craftsmanship to adorn the Torah. The Jewish calendar itself merited an embellished form of material representation. Jews even had special subcalendars, such as the Omer calendar, to count the days from the exodus from slavery to the epiphany at Sinai. In the period between 1750 and 1880, many of the objects transitioned from their original and intended use to become mementos of the past. Even then, they continued to exert their power as objects of inherent dignity. They were witnesses to, if not participants in, a living culture.

Notes

Isaiah Shachar, Jewish Tradition in Art: The Feuchtwanger Collection of Judaica, trans. Rafi Grafman (Jerusalem: Israel Museum, 1981), 12–14, cited in Richard I. Cohen, Jewish Icons: Art and Society in Modern Europe (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 70.