Synagogue Architecture, 1750–1880

Synagogues built in Europe in the age of Emancipation had somewhat contradictory goals. On the one hand, they were to articulate a proud Jewishness, which by definition meant a distinctive style. On the other hand, they wanted to announce that they were deeply embedded in the European cityscape.

Through the period between 1750 and 1880, the built environment inhabited by Jews—neighborhoods, individual dwellings, and buildings used for communal social and welfare purposes—was created in the style of the surrounding environment. “Jewish architecture” is a more difficult category to define, for as a professional trade architecture was not practiced by Jews until later in this period. Yet, all over the world, Jews commissioned, patronized, planned, and built structures for their use, sometimes with the specific intention of making them identifiable as Jewish structures. This is obviously true for buildings intended for religious use such as synagogues, mikvaot (ritual baths), or mausoleums.

Just as the changing interest in ritual objects that had been in continuous use among Jews was spurred in part by the European fascination with antiquities and the archeological discoveries in the Middle East, so, too, interest in a “Jewish” architectural history was sparked in the nineteenth century in the West in part by archeology fever. The discovery of remains of synagogues from the Byzantine period in Israel and the architectural models of the Jerusalem Temple piqued the interest of Jews and non-Jews alike in questioning the character of synagogue architecture. If Jews would be free to build the best structure they could afford, what would it, what should it, look like? Synagogues built in Europe in the age of Emancipation had somewhat contradictory goals. On the one hand, they were to articulate a proud Jewishness, which by definition meant a distinctive style. On the other hand, they wanted to announce that they were deeply embedded in the European cityscape.

One distinctive type of building associated with Jewish culture in the earlier part of this period is the wooden synagogue of Poland. Very few survived the Nazi period, but these buildings, dating from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, bespeak a confident relationship of Jews within their environment. The synagogues were intended to stand out from surrounding buildings both by their height and by their design. They were often located on the outskirts of the original settlement, close to the water. Their exuberant interior decoration testifies to an important and original form of folk art.

Why wood? Laws made it difficult for Jews in that period to obtain permission for masonry synagogue structures, and timber abounded in the rich forests of Poland and Lithuania. Polish synagogues were largely built and decorated by Jewish craftsmen. Prayer spaces for women in the synagogue evolved over time, from small slits in the wall to elaborate galleries with latticed woodwork and separate entrances, possibly indicating an increased presence of women in the synagogues in this period. The large wooden synagogues often functioned as study halls as well as places of worship.

As Jews settled in Western Europe and the Americas, they built synagogues that reflected the spirit of houses of worship of their time and place while also distinguishing the buildings with emblems denoting its Jewish character. (Surprisingly, Stars of David came very late as synagogue adornments.) The second synagogue built in colonial America was the Touro Synagogue of Newport (1763). Its Christian architect designed other noted buildings in Newport, Cambridge, and Boston. Among its many features, the Touro Synagogue has a “secret” trapdoor in the floor of the reading platform, a feature of many colonial American buildings that may have resonated with a Sephardic congregation descended from Iberian refugees. Many of the most elegant synagogue buildings had their main entrances behind gates or facing away from the street.

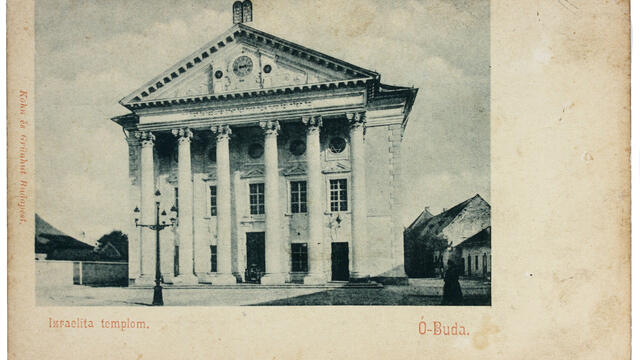

Synagogues in the Western world went through several stylistic phases, with some elements overlapping or mingling in each. Greco-Roman classicism was replaced by references to Egyptian antiquity; from the mid-nineteenth century there was a pronounced turn to orientalism. The “Moorish” style for synagogues, influenced by the Alhambra and by fantasy, took hold particularly powerfully in Central European lands. It also became popular in the United States and in England and France where Jews’ embrace of a “Moorish” style reinforced the argument that they did not truly belong in Europe. This perspective held many positive as well as negative connotations; however, Jews of the time used these tropes to convey their pride in their unique history.

By the early nineteenth century, Jews in large urban areas of Western Europe and the United States commissioned synagogues from the most prominent architects of their time. While the architects of Western synagogues were generally non-Jews in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century, Jewish architects were more common in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Some of the same principles governing Jewish buildings for daily life were echoed in cemeteries. Jews not only designed and decorated gravestones; wealthier individuals and families also constructed monuments and mausoleums that resembled small buildings and expressed their Jewish identity. Jewish grave sites were adorned with Stars of David, candelabra, tablets of the Law, and similar icons identifying the dead as Jews.

Any discussion of built environment must include the central role that Jewish entrepreneurs and industrialists had in building the modern cities of Europe. Often least invested in preserving memories of a difficult past from which they had been excluded, Jews hoped to leave an ordered and beautiful stamp on the shape of the cities themselves. They participated in and sometimes led the construction of railroads and stations, shopping arcades and department stores, new neighborhoods with grand boulevards and elegant apartment buildings, not to mention their own residential quarters. In Paris, the bankers James de Rothschild and Louis Fould, and the developers Émile and Isaac Pereire, left an indelible stamp on the city as they commissioned and built banks, hotels, and entire neighborhoods, buildings that today still signal “quintessential Paris.” An age of fathomless aesthetic possibility dawned for a people whose horizons had been so greatly circumscribed until the nineteenth century