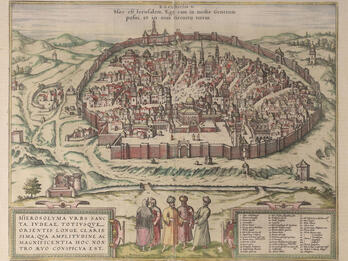

Extremos y grandezas de Constantinopla (Glories and Grandeur of Constantinople)

On the Death of Turkish Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, and Other Events

Death of Sultan Suleiman at the Siege of Szigetvár, and the Wisdom of His Grand Vizier in Dissimulating It

In the days when Sultan Suleiman could take satisfaction in such important victories (not having been ill, but enjoying good health before the Siege of Szigetvár), Death, that punctual executor who treats everyone the same, arrived and carried out the order of the Sovereign Judge. Realizing that Suleiman was dead, Mehmed Pasha, his grand vizier, had him embalmed, as was the custom, demonstrating on this occasion, more than in others, his prudence and sagacity: he kept the death secret so as to avoid the disturbances that often occur at such times, especially as all around them were differing camps and nations (though superficially of the same ilk). Pretending to speak for the king, he gave new orders, that the whole army was to muster at dawn and finish the battle at Szigetvár, impregnable fortress. Two days after the monarch’s death, they emerged victorious and began to pillage, taking many slaves and considerable treasure.

From another Turkish army there now arrived a general named Guiola Pertaph Pasha, who had also been victorious, with spoils of no less importance and quality, having left other castles and lesser places similarly demolished by force of arms, fire, and bloodshed, with hardly a wall left standing.

Mehmed Pasha saw that they must be repaired in order to maintain support and avoid making the king’s enemies doubt his recovery. Indeed, Mehmed Pasha needed to buy time, for he could not keep the great lord’s death secret for long. Fearing that certain signs might make it obvious, he gave an order, pretending it was from Suleiman, that the army should return to Belgrade, where His Highness would stay until all castles and other conquered places should be repaired; and this was done without further delay.

The Grand Vizier Quickly and Secretly Notified the Prince of His Father’s Death

Repairs began on the various strongholds, where a great many soldiers were garrisoned, while the rest of the camp returned to Belgrade. Meanwhile, the Pasha dispatched messengers with all due speed, sending the most effective and diligent in the king’s service to Sultan Selim, his son—located at the time in the plains of Carahisar (known as Sijan Obagi), a suitable place for him, that others know as Chistlaque, of Sinan Pasha—with letters written by his own hand for greater secrecy, in which he informed him of the death of his father; and as discreetly as possible, he went to Constantinople and acquired what he deemed necessary to be well received by the Bustangi Bagi, head of the groundskeepers, in whose care the royal palace had been left; and, similarly, by Schender Bey Pasha, the king’s lieutenant who remained in charge of the city.

He sent many messages, some following directly upon others, giving the same advice: that Selim should go to Constantinople as quickly as possible, and only after he had been sworn in and confirmed as king should he head to the camps and calm the warriors. By this stratagem, they would have learned of his father’s death before they saw him elevated as king.

At the same time, Mehmed Pasha ordered Bustangi Bagi and Schender Bey Pasha that they, as well as the kingdom, should prepare for Selim’s reception; and this was marvelously well done. All these warnings arrived in such secrecy that the very messengers who brought the dispatches did not know what they were about until they saw their effect, leaving them quite amazed.

Some say that the last messengers to reach the prince did not believe his people when they affirmed he was the prince, as they did not know of his father’s death; they therefore resisted giving him the messages they were carrying, and only by force were the messages taken from them.

The king’s death was kept secret until the arrival of his son at the camp because the Pasha had cautiously ordered trustworthy soldiers to guard a bridge over which those coming and going had to pass, telling them to allow no one to cross over, whether of the royal house or not, until King Sultan Selim had first passed over; the result was that those coming could not return before His Highness, and those going could not cross over to spread the news of what had happened.

Credits

Jacob Cansino, trans., “De la muerte del Gran Turco Sultan Soliman y otros sucessos (On the Death of Turkish Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, and Other Events),” in Moses ben Baruch Almosnino, Extremos y grandezas de Constantinopla (Glories and Grandeur of Constantinople (Madrid: Francisco Martinez, 1638), pp. 37–41.

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 5.