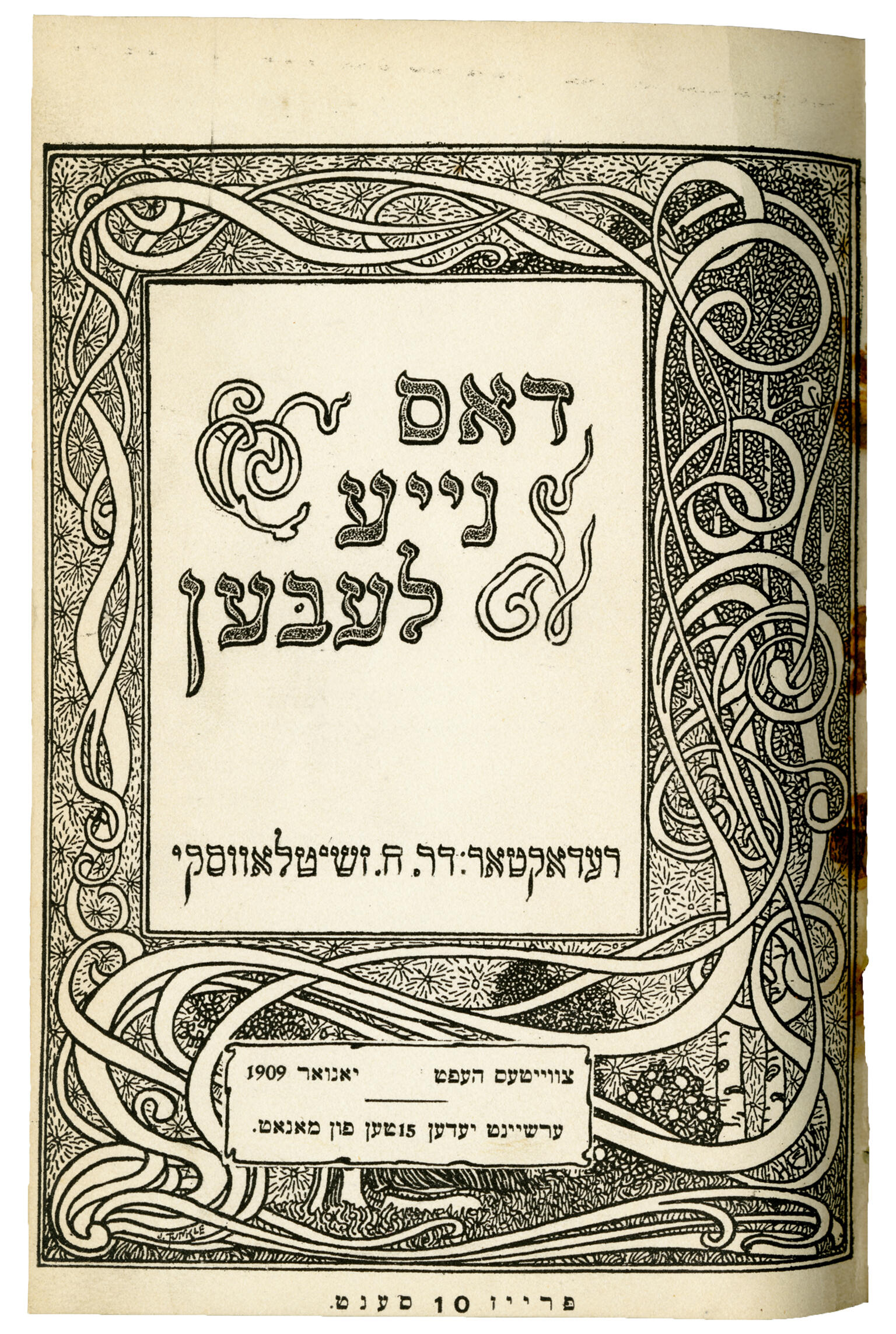

Dos naye lebn (cover)

Chaim Zhitlowsky

1909

Creator Bio

Chaim Zhitlowsky

Russia-born Chaim Zhitlowsky was a theoretician of Yiddishism, diaspora nationalism, territorialism, and revolutionary socialism. He was born near and raised in Vitebsk, Russian Empire (now in Belarus), and had a traditional heder education, as well as a Russian tutor. In his youth, he was drawn to Russian agrarian socialist revolutionary activity. Zhitlowsky initially embraced universalism and distanced himself from Jewish matters but was sobered by the pogroms of 1881 and 1882. He made Jewish political and cultural concerns central to his thought from the mid-1880s onward. At the end of the 1880s, having published his first treatise on Jewish history, Mysli ob istoricheskikh sud’bakh evreistva (Ideas Concerning the Historical Fate of Jewry, 1887), he left the Russian Empire for Western Europe, where he studied German philosophy (completing a translation of Nietszche’s Also Sprach Zarathustra into Yiddish), worked with Jewish socialists of various stripes, and became a leading theorist for those seeking to synthesize socialist and Jewish nationalist ideas. At the same time, Zhitlowsky became an early advocate of a far-reaching Yiddishism that envisioned the transformation of Jews into a wholly secular Yiddish-speaking nation and the creation of a “normal” Yiddish culture possessed of all modern cultural institutions (he called for a Yiddish university in 1902) and completely open to all ideas and aesthetic trends, not just ones drawn from Jewish tradition. In 1908, Zhitlowsky helped organize the Czernowitz Yiddish language conference. After 1908, he spent increasingly more time in the United States, where he eventually settled. There, Zhitlowsky championed Yiddish language and culture, which he considered necessary for the continued health of the Jewish people. He was instrumental in establishing a network of Yiddish-language secular schools in the United States. Zhitlowsky also traversed the Jewish political spectrum in idiosyncratic ways, seeking to ground his vision of a flourishing Yiddish secular nationhood variously in diaspora nationalism, territorialism, and Soviet communism.