Crónica de los reyes otomanos (Chronicle of the Ottoman Kings)

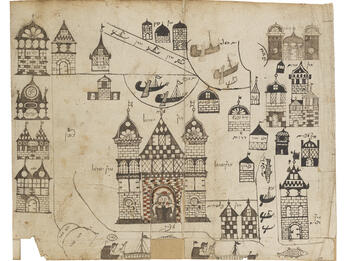

The Houses of Constantinople

The houses and rooms of the inhabitants of this most famous city are one or the other of two extremes: the good ones are sumptuous houses at the height of perfection and the others are low, uninhabitable, dark, fetid, suffocating, freezing cold in winter and very hot in summer.

And the cause of this is manifestly clear: since it is a city with a court of infinite numbers of people and great lords, an inch of ground is worth its weight in gold and worth much more to build on it. [ . . . ]

And since the place is very narrow, especially in the Jewish Quarter, every space of the courtyard built upon, and they try to make the best of dwelling high up, so that it will be open to the north wind, which is healthy, and consequently the low-lying houses remain very dark without allowing for breathing in any room. [ . . . ] And because the city is very humid, and the lower and closer it is to the ground the more humid it is, in winter the humidity freezes up and makes it colder. And in summer, since there is no place for fresh air to come through, the lower part remains closed on all sides and is extremely hot, and thus it is so badly affected that it is uninhabitable.

The Tradesmen

Those who come to do business in this city at the door of the king or of his favorites and great lords never conclude their business except under one of two extreme conditions: either they have much money to spend or have no money to distribute. And the one who wishes to spend moderately cannot do so nor conclude his business.

And the reason for this is that whatever the business may be with whichever lord for money, many intermediaries and negotiators interpose themselves and wish to participate in it, [ . . . ] and the more they bribe the lord with whom they negotiate, the more they ingratiate themselves with him.

And the person who does not have the ability to give all these people as much money as they demand gets nothing done, because when one of them [the intermediaries] is unsatisfied, he alone can thwart all that all the others have agreed upon. And when the one who negotiates [the businessman] doesn’t have enough, or doesn’t wish to spend all his money in his transaction, even though he places the business in danger of turning out differently from the way he wishes, he ends it rapidly and is summarily dismissed. [ . . . ]

The Women

The women—the virtuous ones among them, who are the majority—are so honest and retiring that however familiar the man may be in the house, he does not talk to them, and neither are they seen by anyone; and those who are not virtuous, who are very few and from the lower class of people, are so dissolute that one [a man] has more conversation with them than with their husbands.

And the reason for this is because the houses of Constantinople are very narrow, as we have mentioned, and do not have space in the buildings to make a patio courtyard or verandas, since they extend upward rather than lengthwise or widthwise.

And since the women do not have any place to spread out or to converse with any neighbor, the most virtuous and most generous, who are the majority, are forced to retire into their chambers with their daughters or slaves, totally enclosed, embroidering or doing some other activity. And since they are accustomed to this and are not accustomed to do laundry or wash dishes, or to do similar things, which is all done by the slaves or by women who have been hired for this, they do not even go into the salon as long as people are there, however closely related these people may be.

And those who are not very virtuous and do not consider being dissolute a dishonor, since they have no other place to move about or converse other than at the windows and doors and public places that open onto the street, from these they converse and chat with men and women who are in other windows across from them and on each side and with those passing in the streets. This habit of theirs, together with the leisure time which they continually have because they are without a moment of work, makes them so dissolute that they never leave the windows and doors, and from there they can communicate and converse with everyone, both men and women.

And the low-class women, when they come to this extreme, place themselves in shops in place of their husbands to buy and sell, the way that their husbands perhaps do, with much authority and consistent order.

Credits

Moses Almosnino, “Crónica de los reyes otomanos (Chronicle of the Ottoman Kings)” (manuscript, Salonika, 1567). Published as: Moses ben Baruch Almosnino, Crónica de los Reyes Otomanos, ed. Pilar Romeu Ferré (Barcelona: Tirocinio, 1998), pp. 175, 178–179, 223–232, 235–269.

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 5.

![M10 622 Manuscript, probably from Ukraine]. Manuscript probably from Ukraine, c. 1740 with a broad collection of practical kabbalah and mystical magic. Facing page manuscript arranged vertically with Hebrew text in the shape of a figure wielding two long objects.](/system/files/styles/entry_card_sm_1x/private/images/vol05/Posen5_blackandwhite166_color.jpg?h=cec7b3c9&itok=Sz6u21MQ)