Jewish Culture in Postwar Europe

As European Jewish communities tried to rebuild after the Holocaust, they faced new challenges and forged identities distinct from those in Israel and the United States.

Jewish writing and political thought in Europe after 1945 was consumed by the challenges of postwar reconstruction, fears of renewed conflict between East and West, and grim memories of destruction and betrayal. The same Europe that had inspired generations of Jews with promises of liberalism and progress had witnessed the greatest disaster in Jewish history. And although some non-Jews intervened to save their Jewish neighbors during the war, frequent cases of collaboration with the Nazi occupiers left widespread ripples of mistrust in the aftermath.

Western Europe

Jewish survivors returning to their former homes in France and the Netherlands encountered indifference and even hostility, especially when they tried to reclaim their homes and property. In the aftermath of widespread collaboration and German occupation, many Europeans wanted to subsume uncomfortable memories of Jewish suffering in a general narrative of resistance, rather than work to restore what was left of the European Jewish community. Indeed, the reemergence of European Jewry was far from certain.

Jewish survivors had to take stock and ask themselves on what terms they could again become French, or Dutch, or Italian. Everywhere in Europe, on both sides of the Iron Curtain, Jews discovered, in those first years after the war, that few people wanted to hear their stories or recognize their suffering. In the Soviet Union and the satellite countries of Eastern Europe, communist leaders used their supposedly universalist ideology to spread an invidious antisemitism that erased Holocaust memory, justified discrimination, and resulted in the murder of Jewish writers and poets.

Jean-Paul Sartre, in his foundational series of essays Reflections on the Jewish Question, written in 1944, argued that the Jew was largely a creation of the antisemite, his sense of his identity and history dependent on a memory of suffering and persecution. But events soon proved Sartre wrong, and the postwar world witnessed a surprising resurgence of Jewish self-confidence. While Jewish thinkers in Europe and the United States welcomed Sartre’s condemnation of antisemitism, they adamantly rejected his claims that Jewish identity was a creation of non-Jews. Indeed, a Europe compromised by war and fascism could learn a great deal from Jewish values. For instance, in his 1947 response to Sartre, the French Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas asserted that the Jew not only had a positive identity of his own but also carried a message of universal importance. “The Jew,” Levinas wrote, “is the entrance itself of the religious event in the world, better yet it is the impossibility of the world itself without religion.”1 Judaism, Levinas believed, offered Europeans a way out of a fateful deadlock between land-and-soil determinism and abstract transcendent universalism. Grounded in rabbinic texts, Judaism emphasized mutual responsibility, which demanded constant attention to specific situations and concrete obligations toward others. Meanwhile, writing in German, Martin Buber, Ignaz Maybaum, and others also defiantly asserted Jewish relevance. The lessons of German Jewry’s long struggle for dignity, equal rights, and the best ideals of German humanism mattered more than ever for a German nation tarnished by a total moral collapse. However shaken by the Holocaust, European Jews, Maybaum argued, still had a role to play as a community distinct from both Israel and North America and perhaps in the future, as a bridge between Russian Jews and world Jewry.

By the mid-1960s, some Jews mused out loud about the need for a new, “European” Jewish identity that would complement the growing movement toward European integration and serve as a link between East and West. For its champions, such a vision of cosmopolitan European Jewishness also represented an alternative to the two dominant ethnic Jewish communities of Israel and the United States that emerged in the wake of the Holocaust. It heralded the revival of a distinct European Jewish sensibility, creative and connected to deep historical roots.

Literature in Postwar Western Europe

As the children of Jewish immigrants gained acceptance in postwar Britain and Western Europe, a certain genre of life writing appeared that reflected the successful navigation of a road that led to recognition and success and thus made it safe, and even important, to reflect back on one’s Jewish roots. In Two Worlds: An Edinburgh Jewish Childhood, the eminent writer and literary critic David Daiches recalled his formative years in Edinburgh, where his father was the chief rabbi of Scotland. He found absolutely no contradiction, no tension, between those two worlds: the Jewish world, which he evoked in his memoirs, and the Scottish world in which he lived. Tellingly, both the Jewish and the Scottish identities put forward claims of difference; both staked out their own space in the much wider universe of “British” or “English-speaking” culture.

These claims to difference in wider cultural spheres, anchored in the relatively safe space of family and memory, not only marked life writing; they were also important themes of fiction and poetry by European Jewish writers, especially in France, where Jewish writers began to enjoy unprecedented prominence beginning in the 1960s. Tunisian-born Jacques Zibi’s Mâ measured the distance between his new life in France and his Tunisian Jewish childhood. The latter was anchored in a warm, traditional home, a mother’s love, and an Arabic-Jewish dialect gone forever. Corfu-born Albert Cohen’s Her Lover (Belle du Seigneur) evoked the sometimes hilarious, sometimes poignant contrasts between his earthy origins and his urbane reincarnation as a successful French diplomat. Underneath the comedy and the brilliant style lie more somber reminders of the bonds of time, family, place, and memory—and Jewishness.

Just as the French Jewish community was being transformed by large-scale immigration from North Africa, French Jewish writers began to have a major impact on a nation struggling to come to terms with its ambiguous record in World War II. Two works in particular, André Schwarz-Bart’s 1959 The Last of the Just, which won the Prix Goncourt, and Jean François Steiner’s 1967 Treblinka, caused major controversies by highlighting such themes as the Christian roots of antisemitism, French complicity in the Holocaust, and, in Steiner’s case, the paradoxical interplay of Jewish passivity and Jewish resistance. These books made the Holocaust more visible as an event separate from World War II.

Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union

Behind the Iron Curtain, opportunities to write Jewish-themed poetry and fiction, mainly about the Holocaust, opened and closed depending on the political climate. In Poland, Adolf Rudnicki, who wrote relatively little on Jewish themes before the war, penned some of his most powerful fiction on the destruction of Polish Jewry. In 1951, he published a short story, “The Ascension,” in which a young woman faces a stark moral choice that forces her to ask what ethical price she will pay to survive.

Another Polish-language masterpiece of Holocaust literature is Bogdan Wojdowski’s 1971 Bread for the Departed. Wojdowski, who had survived the Warsaw ghetto as a child, evokes the disruption and confusion of the ghetto as seen through the eyes of a young boy, David Fremde. Instead of a plot, there is a depressing kaleidoscope of scenes often narrated in the chaotic, deformed “ghetto speak” that alone provided the right words to describe what David saw.

A very different kind of novel, this time about the Łódź ghetto, was Jurek Becker’s 1969 Jacob the Liar, written in East Germany. Becker was a Holocaust survivor, and he brilliantly decoded ghetto life by highlighting lies and illusions enlisted to fight despair. These powerless, isolated denizens of the ghetto used their only weapon—words—as they analyzed and parsed the optimistic lies that Jacob disseminated based on his fictitious ghetto radio.

In the postwar years, two Jewish writers born in Eastern Europe and writing in their nonnative French produced Holocaust fiction that broke new, artistically daring ground in the representation of atrocity: Piotr Rawicz’s 1961 Blood from the Sky and Romain Gary’s 1967 The Dance of Genghis Cohn (not included in the Posen Library). Both Rawicz and Gary (born Roman Kacew) were masters of acquired identities, a talent that frightened antisemites even as it bemused many Jews. The former’s use of multiple angles of narration and representation make it a classic of Holocaust literature, as Rawicz uses the perspective of different voices, none necessarily reliable, to describe atrocity with a frankness that spares no one, including Jews.

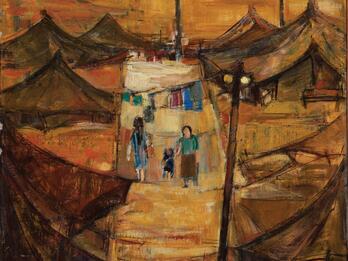

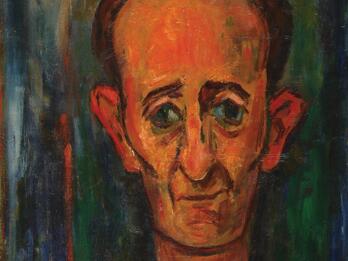

Judaism behind the Iron Curtain

If in the early postwar years the fate of Jews behind the Iron Curtain was largely a closed book to world Jewry, by the middle of the 1960s, this was no longer the case. Important analyses of Polish and Soviet Jewry appeared in both the émigré press and illegal publications, the so-called samizdat. Polish Jewish intellectuals, such as Zygmunt Bauman, offered important insights into the dynamics of antisemitism in the communist bloc and hammered another nail into the coffin of what used to be the Jewish romance with the communist left. In the Soviet Union itself, some embers of Jewish culture continued to glow: concerts of Yiddish song, some high-quality poetry and fiction in the journal Sovetish heymland, the art of Anatoly Kaplan, Zinovii Tolkachev, and Mikhail Grobman. As an artist attached to a propaganda unit in the Red Army, Tolkatchev drew sketches of Maidanek in 1944 and Auschwitz in 1945. The first artistic renderings of these Nazi camps after the liberation, they captured the bittersweet interplay of the joy of freedom and the anguish of bereavement, and his emotional involvement not only as a Soviet soldier but also as a Jew.

A key development of this period, with worldwide ramifications, was the startling emergence of the Soviet Jewry movement and the national awakening of Soviet Jewry itself. An interplay of simultaneous activism—inside and outside the Soviet Union—reflected growing communication between different Jewish communities. Galvanized by the Six Day War, the civil rights struggle in the United States, the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia, and a sensitivity to the lessons of the Holocaust, the Soviet Jewry movement marked an important milestone in postwar Jewish history. Thanks to this movement, which mobilized both religious and secular Jews in the United States and elsewhere, essays written in the Soviet Union, which could be published only in the clandestine press, nonetheless found a receptive audience in the Jewish world.

Notes

Emmanuel Levinas, “Être juif,” Confluences 7 (1947): 261.