The Holocaust: Years of Catastrophe

Jewish writing in Nazi-occupied areas documented ghetto life, moral questions, and Jewish identity, while writers in free zones grappled with the unfolding tragedy.

In 1939, just before the outbreak of World War II, the situation for the Jewish people in Central and Eastern Europe looked bleak, even desperate. Hitler claimed that world Jewry was a demonic power harnessing the sinister forces of plutocracy and communism to plunge the world into war, destroy Germany, and rule the world. In fact, Jews were vulnerable, politically weak, and divided. In the face of looming danger, whether they lived in Eastern or Western Europe, Palestine or the Americas, Jews were separated into warring camps by political and cultural infighting.

The doubts and defeats of the 1930s left their mark on Jewish writing in all genres during the Holocaust, in the areas both within and outside of Nazi control. Some asked whether Jewish faith in European liberalism and Enlightenment values had been misplaced. Others wondered whether Jews had found themselves stranded midstream, no longer secure in their age-old religious tradition but unable to find acceptance in the non-Jewish world. Still others held fast to a universal Marxist vision or a Jewish national alternative. But alongside despair and doubt, new notes of pride and self-affirmation also emerged, sometimes quite unexpectedly. The literary output of this period certainly belies the widely believed claims that the ghettos under Nazi rule were a cultural wasteland or that Jews in areas outside Nazi influence knew little about the unfolding disaster.

Writing in the Ghetto during the Holocaust

Texts composed in the lands under Nazi occupation or influence differed dramatically from those written in the “free zone.” In Eastern Europe, more than elsewhere, Jews wrote not just as individuals but also as part of a national collective. To a large degree, this reflects the impact of prewar cultural traditions: a highly developed sense of common Jewish identity and an intense ideological engagement. These texts, mostly in Yiddish, underscored such themes as resistance, the moral state of the Jewish people, Jewish attitudes to European culture and Enlightenment traditions in the wake of the Holocaust, the future of the Jewish people after the Holocaust, and finally, religion. Little could match the sheer urgency and intensity of what came out of the ghettos.

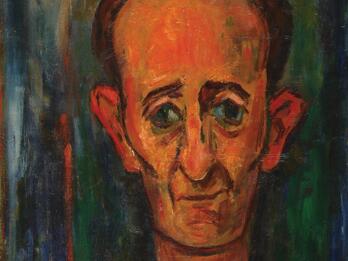

Much of the life writing from the ghettos reflected an ongoing tension between knowledge and false hope, the witnessing of destruction and the delusion that perhaps survival might still be possible. In these unique societies—each ghetto being quite different—slang and street songs replaced newspapers; language changed at warp speed. Spontaneously assembled knots of neighbors and passersby listened to songs about murdered spouses and orphaned children, about Judenrat corruption and the struggle to survive, about rich and poor, about the privileged and the dying, about deportations and about hopes for a better future. The writers of diaries and reportage had to find the right words to make the ghetto experience legible, to describe what eluded description, and to decode a world that defied easy understanding. The act of writing was an assertion of one’s humanity and served a moral mission; indeed it could, to quote Gustawa Jarecka, a contributor to the secret Ringelblum archive, “cast a stone under history’s wheel.” Diarists saw their diaries as their most important reason for staying alive. While some diaries were mainly personal, others possessed a collective focus, aimed at documenting ghetto life. This was also true of ghetto photographers and artists like Esther Lurie in the Kovno ghetto or Mendel Grossman in Łódź.

While Jewish writing in the ghettos and camps certainly included calls for resistance and spiritual defiance, it also touched on less heroic topics: anger at other Jews, betrayal, corruption, the destruction of the family, the terrified waiting for the next blow. Jewish realization that the Germans intended to kill them marked a crucial moment, separating what came before from what came after. Leyb Goldin wrote his naturalistic “Chronicle of a Single Day” for Warsaw’s Oyneg Shabes archive in the summer of 1941, when Jews could only guess their future. And Simkhe-Bunem Shayevitsh wrote “Lekh-Lekho” when he still had a daughter to talk to, before the Germans murdered his wife and two children. Ghetto writing, however, and especially its poetry, also marked the remorseless descent toward the abyss.

Writing in Western Europe during the Holocaust

The diaries and writings of Western European Jews, along with letters, underscore some major differences between Holocaust-era writing in Eastern and Western Europe. Most of the writers from Eastern Europe saw themselves first and foremost as Jews. While some Jews may have written in Polish, and while many certainly loved Polish culture, most did not consider themselves Poles. But in Western Europe, Jewish writers often felt much more integrated and saw no contradiction between being French or Dutch and Jewish. All the more brutal, therefore, was the shock of betrayal as French Jewish writers pondered the stark contrast between how they saw themselves and how their origins determined their fate.

Writings such as Paul Ghez’s Six mois sous la botte (Six Months under the Boot) described the fraught experiences of a Tunisian Jewish community leader during the relatively short six-month German occupation, from November 1942 to May 1943. He included the brutality of the labor camps and the collaboration between Arabs and the local French population in their persecution of the Jews.

Outside the world of Yiddish, a major question was not whether to accept European culture—that was a given—but to show how much Jews had helped make it. Across the Atlantic, German Jewish exiles tried to come to terms with the disaster in Europe by explaining the wider historical context for fascism and antisemitism. Antisemitism, they argued, was not just a Jewish problem but a serious threat to any stable democracy.

Another German émigré, Hannah Arendt, asked why legal emancipation made the Jews more rather than less vulnerable. Quoting Franz Kafka in her essay “The Jew as Pariah: A Hidden Tradition,” Arendt stressed that “only within the framework of a people can a man live as a man among men.”

Writing in the “Free Zone” during the Holocaust

The question of how Jews in the “free zone” reacted to the Holocaust is a fraught one. A group of young students at the Jewish Theological Seminary angrily accused Jewish leadership of doing far too little. The Bundist leader Artur-Shmuel Ziegelboym killed himself to protest the indifference of the allies to the murder of Polish Jewry. Arthur Koestler noted that decent people in the West paid more attention to the accidental killing of a dog in the street than they did to the Holocaust. And the Lubavitcher Rebbe at the time saw Jewish suffering as heralding the birth pangs of the Messiah.

Responses to the catastrophe varied. Some, like Sofia Dubnova Erlich, Puah Rakovsky, or I. J. Singer turned to life writing to challenge the retrospective glow of false nostalgia while using individual experience to convey a new awareness of the diversity and reality of East European Jewry. Others, like Michael Molho, in his Traditions and Customs of the Sephardic Jews of Salonica, focused on the everyday, the material culture, routines of life that reflected the ethos of a rooted and devoted community in a fascinating parallel to the work of the ghetto archives. Still others turned to poetry and prose.

Taking full advantage of a temporary thaw during the war, Soviet Jewish writers reaffirmed their Jewish pride and mourned the Holocaust. Soviet Jewish photographers like Yevgeny Khaldei and Dimitri Baltermants documented not only the struggle of the Red Army but also the murder of the Jews. But even in the middle of the wartime thaw, some Soviet Yiddish poets, including Peretz Markish, had uneasy forebodings about the future, expressed in his poem “Shards.” In Brazilian exile, the brilliant, assimilated Polish-language poet Julian Tuwim wrote, “We Polish Jews,” an unambiguous gesture of solidarity with his murdered people. In the United States, Rabbi Milton Steinberg’s As a Driven Leaf and Sholem Asch’s daring and controversial Yiddish novel The Nazarene pushed back against rising antisemitism by returning to the distant past of Roman-occupied Palestine to show Christian indebtedness to Jewish morality and to explain why the allegedly superior Greco-Roman culture ultimately lacked the ethical core that only Judaism could provide.