Theodicy, or Why Good People Suffer: The Biblical Book of Job

The book of Job asks why bad things happen to good people, as an entry point into questions about the relationship between God and humans.

The book of Job touches on a number of the most important issues in religious thought: the reason for suffering, divine justice, human intellectual integrity, and the motivation for piety. Often described as wrestling with the question of why the righteous suffer, it is, more broadly, a quest for knowledge about the nature of God and the universe, and the place of humans in it. It is essentially an inquiry into human and divine wisdom, about the possibility of arguing against accepted truths, and about exploring the human condition.

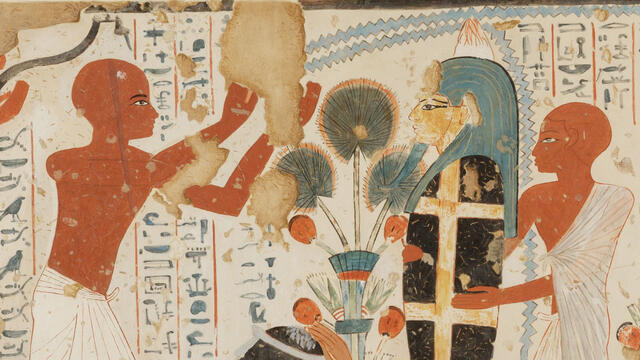

The book is rhetorically sophisticated and artfully structured. The central structuring device is the dialogues between Job and each of his three friends in turn. The dialogue, or disputation form, is familiar in ancient Near Eastern wisdom literature, from both Egypt and Mesopotamia, and is perhaps best known from the symposia of ancient Greece. The book’s vocabulary is extensive and at times esoteric, and numerous Aramaic or Aramaic-like words add to the foreignness and the learnedness of the discourses. Rhetorical questions are another feature of the book, as are extended lists and descriptions. This is perhaps the most difficult book in the Bible, both in its thought and in its literary expression.

A prose narrative frame, consisting of a prologue in chapters 1–2 and an epilogue in 42:7–17, surrounds the dialogues, which are in poetic form. The frame draws on an apparently ancient folktale (see Ezekiel 14:14, 20), retold in a highly structured manner to introduce Job, a sinless man who suffers great losses but refuses to blame God. The prologue is arranged as scenes that alternate between earth and heaven. The poetic speeches that constitute the body of the book move back and forth between Job and each of his three friends, Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar, for almost three rounds (Bildad’s third speech is short and Zophar lacks a third speech). Job, with increasing vehemence, denounces God’s injustice, while his friends respond by defending God’s justice and arguing that Job must have sinned. The friends’ arguments are supplemented by a fourth speaker, Elihu, who is introduced in chapters 32–37. (Scholars think that Elihu is a later addition.) God, too, speaks, in chapters 38–41, with Job responding. In the epilogue, God rebukes the friends and restores Job to his former state. Standing outside of the dialogic structure is chapter 28, a poem about wisdom.

The book is generally dated to the Persian period, probably during the fifth–fourth centuries BCE.