Living a Good Life according to Biblical Wisdom Literature

Biblical wisdom literature shares the educational and intellectual traditions of the broader ancient Near East.

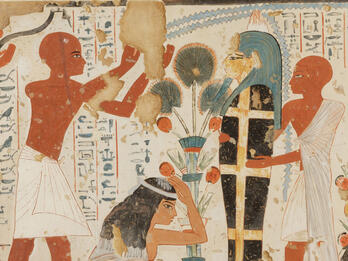

All societies want to teach their values to their members, especially to the young. They also ponder the workings of the cosmos, posing difficult questions about the meaning of life, the nature of the universe, and similar issues. The biblical works represented here, often called “wisdom literature,” share the educational and intellectual traditions of the rest of the ancient Near East. Indeed, the Bible respects the wisdom of “the sons of the East,” the paradigm for wise men. For example, Job is not an Israelite, and the book of Proverbs includes teachings from foreigners: Agur, from Massa (Proverbs 30), and Lemuel, king of Massa (Proverbs 31:1–9). A number of ancient Near Eastern works have much in common with biblical wisdom literature, including didactic collections, such as the Egyptian “Instruction of Amenemope” that appears to have influenced part of the book of Proverbs, and works about innocent sufferers reminiscent of the book of Job. Wisdom literature has a practical dimension, as seen in the book of Proverbs, which teaches how to comport oneself in order to succeed in life. It also has a speculative dimension, as in Job and Ecclesiastes, which are concerned with more abstract ideas and raise problems that cannot easily be solved.

Biblical wisdom literature focuses on human thought and behavior. It rarely deals with religious observance, and some of it does not seem specifically Israelite. But it assumes belief in God, and it makes the existence of God a central tenet. “Fear of the Lord”—that is, conscience, based on the recognition of God’s power in the universe—is the primary principle of wisdom; it appears in Proverbs, Job, and Ecclesiastes. Without fear of the Lord, there can be no wisdom; wisdom leads to greater appreciation of God’s power and will. In addition, although wisdom may lack a ritual component, it has a clear moral component. Indeed, in the ancient world, unlike in the modern world, it was impossible to separate religion from the rest of life. Ultimately, even in the late biblical period, and certainly more clearly in later times, the concepts of wisdom and “Torah” coalesced. The value of acquiring wisdom became equal to acquiring Torah, God’s word as revealed to humans. The verse in Proverbs 3:18, “She is a tree of life to those who grasp her, and whoever holds on to her is happy,” is referring to wisdom but has come to be understood as referring to Torah.

As the just-quoted verse shows, wisdom, often personified as a woman, became an almost-tangible entity. In biblical thought, God created the world with (the help of) Wisdom (Proverbs 3:19), suggesting that wisdom is a primary element or principle of the cosmos and that Wisdom informs the cosmic order (Proverbs 8:22–36; Job 28).

In wisdom literature, “wisdom” refers to moral-religious knowledge. Elsewhere in the Bible it embraces other forms of knowledge and skill, including what we might label as science, the arts, business, magic, and military stratagems. We see this in the description of Solomon’s wisdom:

9God endowed Solomon with wisdom and discernment in great measure, with understanding as vast as the sands on the seashore. 10Solomon’s wisdom was greater than the wisdom of all the Kedemites and than all the wisdom of the Egyptians. 11He was the wisest of all men: [wiser] than Ethan the Ezrahite, and Heman, Chalkol, and Darda the sons of Mahol. His fame spread among all the surrounding nations. 12He composed three thousand proverbs, and his songs numbered one thousand and five. 13He discoursed about trees, from the cedar in Lebanon to the hyssop that grows out of the wall; and he discoursed about beasts, birds, creeping things, and fishes. 14Men of all peoples came to hear Solomon’s wisdom, [sent] by all the kings of the earth who had heard of his wisdom. (1 Kings 5:9–14, NJPS)

These verses are likely the source of the tradition that Solomon was the author of the biblical books of Proverbs and Ecclesiastes (as well as the Song of Songs).

Wisdom teachings may take the form of individual sayings or allegories (see Sayings, Riddles, Fables, and Allegories), but there are also longer wisdom discourses in Proverbs, Job, Ecclesiastes, and the extrabiblical Words of Ahiqar. The first three as well as parts of Ahiqar are written in poetic lines. They often incorporate proverbs and proverb-like statements into their discourses and also employ speeches and dialogues and quotations. They do not develop their points in a sequential fashion but rather revisit earlier points from different perspectives.