Haskalah and Pedagogy

The first maskilim ransacked both Jewish and European tradition to find new platforms for creating and transmitting the Jewish cultural ideals they conceived. Jews enlisted diverse literary genres to call for social, educational, and economic change.

Until the latter half of the eighteenth century, religious skepticism and calls for reform of various aspects of Jewish life remained individual expressions. They did not coalesce into movements that would overturn the structure of Jewish life and its hierarchy of values. When such movements began to take shape, they developed against an efflorescence of traditional rabbinic culture determined to hold the forces of innovation at bay.

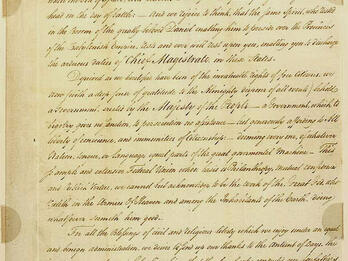

One of the first programmatic statements came from the pen of Naphtali Herts Wessely. Reacting to the Toleranzpatent issued by the “enlightened despot” Joseph II of Austria, Wessely issued an epistle, Divre shalom v’emet (Words of Peace and Truth, 1782), calling upon Jews to abandon the deadened rabbinic culture with its talmudo-centrism and to reorient Jewish culture toward the full range of Hebraic knowledge as well as other languages, and the natural and exact sciences.

The Haskalah’s influential embodiment and philosophical icon was Moses Mendelssohn. An accomplished philosopher celebrated as the “Socrates of Berlin,” Mendelssohn addressed many conundrums of his time while adhering to and defending observant Judaism.

The first official maskilic circle and the first printed journal for maskilim were founded by Isaac Euchel in Königsberg. Over the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Haskalah ideals and pedagogy slowly expanded and provided intellectual underpinnings for further movements of Jewish modernization. In formerly Polish (then Austrian) Galicia, in cities such as Brody, Tarnopol, and Lemberg (present-day Lviv), maskilic culture saw the traditionalist Hasidic movement as the foremost obstacle to Jewish modernization. In Russia, maskilic ideals, formulated in a programmatic essay by Isaac Ber Levinzon (1828), took root first in cities such as Odessa and Vilna. Yet the illiberalism of the society itself, from the tsar down, made it far more difficult for even the most committed enlighteners to effect meaningful change. While the scholarly circles around the Gaon of Vilna and his disciples embraced a rabbinic rationalism and openness to the sciences as bold as those of any enlightened figures, Jews in Eastern Europe did not turn to the larger culture en masse until the late nineteenth century.

The first maskilim ransacked both Jewish and European tradition to find new and better platforms for creating and transmitting the Jewish cultural ideals they conceived. From translations of sacred Jewish texts to autobiographies and “dialogues of the dead,” Jews enlisted diverse literary genres to call for social, educational, and economic change. By the late nineteenth century, they had stimulated a profound recasting of Jewish literary culture in Hebrew and in Yiddish.

Questions of language were always political and deeply intertwined with those of Jewish education. A basic component of the traditional Jewish educational system (mainly for boys) had been the translation of the Bible into a stylized form of the vernacular—Yiddish-taytsh, Ladino, and Sharkh (Judeo-Arabic). In the Islamic world, Western Jewish, as well as non-Jewish, imperial and colonial cultural influences broadened educational choices. European Jewish schools, Christian missionary schools, and Russian and Ottoman state schools all competed with traditional Jewish schools in the nineteenth century. The modernization of curricula in Western-influenced schools was essential to the realization of maskilic goals.