Folk Tales and Fiction

The “return to history” of Jews in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and engagement between Jews and their majority cultures offered new models for imaginative writing beyond those within their ancestral traditions.

The “return to history” of Jews in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and engagement between Jews and their majority cultures offered new models for imaginative writing beyond those within their ancestral traditions. Belles lettres had been cultivated by Jews in many cultural milieus in the past, but perhaps none with the ardor and all-encompassing passion of this period in which literature became one of the chief ways of entering (as well as countering) modernity. Far more than in other realms of cultural creativity, such as visual fine arts and music, Jewish writers tended to engage with openly Jewish characters, themes, and stories. Jews of the past wrote polemics and poetry, midrash and miracle tales, scholarship and manuals, but they had not yet written novels.

The Beginnings of the Jewish Novel

Scholars of literature differ over how and where to locate the origins of the novel, the literary genre most closely identified with European modernity itself. Some argue for unbroken continuity since antiquity, whereas others name Miguel de Cervantes, Daniel Defoe, or Samuel Richardson as the first modern novelists. Early novels tended to mimic existing prose genres such as diaries, epistolary exchanges, or travel writing. Richardson’s Pamela (one candidate for the first “real” novel) was an epistolary novel, as is Isaac Euchel’s Igrot Meshulam (Epistles of Meshulam, 1790), modeled after Montesquieu’s Lettres persanes (1721), which embodies the search for new genres by writers in Hebrew. The first attempts by Jews tended to serve didactic or ideological ends. The “realistic” novel, the genre whose purpose was to transport the reader to an alternative yet familiar world for the sake of the imagination alone, emerged gradually as a mature field of Jewish creativity. By the later decades of the nineteenth century, Jewish authors had mastered the art of novel writing in European languages.

Writers faced questions not only concerning the best language to reach their readers but also on how to shape their story, how to portray their characters, and how to balance their message with the aesthetic value of their prose. Ruth Wisse has argued that while European novelists exalted the “man of action” who influenced his own and others’ destiny, Jewish writers could not easily “acclaim the man of action as their authentic Jewish hero.”1 They did not have the political or military experience that European Christians had, and so they ended up creating what she calls the comic hero, a compromise of sorts. Apropos of her remarks, it is notable that one of the most accomplished statesmen, Benjamin Disraeli, often did choose “men of action” as his literary heroes.

Writing a novel requires an author to conjure an entire world with language. This was a daring venture in any language, but it was doubly so for Hebrew and the Jewish vernaculars, each for different reasons. As Robert Alter notes, “To write a novel in Hebrew . . . was to constitute a whole world in a language not actually spoken in the real-life equivalent of that world, yet treated by the writer as if it were really spoken.”2 The first Hebrew novels were written in biblical idiom, some even based on biblical characters, as authors searched for the noblest language in which to create, then reached back several millennia to find usable precedents. Decades later, as authors added rabbinic and other registers of Hebrew to the literary palette, Hebrew novels lost their stiff diction and became far more linguistically rich and supple. Still, novels written in the Hebrew of the nineteenth century would always remain the province of a very small and committed readership, mainly educated, secular, yet Hebraically literate young men.

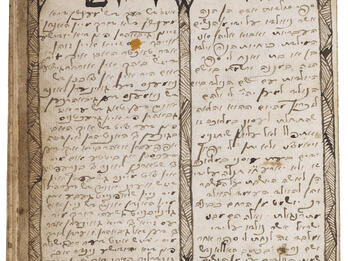

In Eastern Europe, the lingua franca of the masses was Yiddish, and to create fine literature in that language presented its own challenges. For all its widespread use in the daily life of millions of Jews in Ashkenazic Europe, west and east, Yiddish was thought of by literary arbiters as a lowly jargon, a coarse pidgin dialect with no grammatical structure, no beauty, no literary past, and no future. Writers of this period such as Isaac Meyer Dik and S. Y. Abramovitsh opened the way for others who wove the unpromising language into a literary fabric of unanticipated depth and richness.

Diversifying the Jewish Literary Tradition

Folktales reappeared in the nineteenth century, sometimes as sophisticated replicas of their naïve early selves, having been appropriated by savvy masters to play their nostalgia value for ideological ends. Writers and storytellers living in (or trying to capture the bygone flavor of) traditional societies used folktales as a means to reach the largest readership and to convey lofty messages with their stories.

Jewish writers used literature not only to reckon with a Jewish past many wished to jettison or reshape; they also addressed the multiple and entangled aspects of their new reality. Thus the figure of Jews serving in the military appears in the art and letters of this period. Reversing a centuries-long aversion on both sides, Jews entered the armed services of various nations and distinguished themselves in combat, learning to graft their military training onto their Jewish identities. Some writers and artists evoked the pride felt by Jewish families in the West for whom serving in the military signaled the most honorable place in society.

Novels and short stories advanced a host of ideologies through their characters, from enlightenment to nationalisms in all their complexity, as well as socialism and communism. They explored the consequences of romantic love, class disparity, and the glories of the natural world as they invented a vocabulary for a reality that had seemed beyond their grasp only a short while earlier. Heinrich Heine, one of the most versatile and gifted stylists writing in German in the nineteenth century, left no subject untouched, although he frequently returned to Jewish themes.

Jewish women also played important roles in the creation of Jewish literature in the vernacular, entering into writing careers previously closed to women and becoming some of the most significant voices of the period. In England, Grace Aguilar wrote poems, stories, and histories, with special emphasis on the converso experience, Sephardic history, and Jewish women. In the United States, Emma Lazarus produced an astonishing bounty of literary works in multiple genres. Although she is remembered today primarily for her famous sonnet “The New Colossus,” inscribed on the Statue of Liberty, she and Aguilar can be considered among the most important nineteenth-century Sephardic writers in English.

Notes

Ruth R. Wisse, The Modern Jewish Canon: Journey through Language and Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 31.

Robert Alter, The Invention of Hebrew Prose: Modern Fiction and the Language of Realism (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1988), 5.