Life Writing: Biography, Autobiography, and Ego Documents, 1750–1880

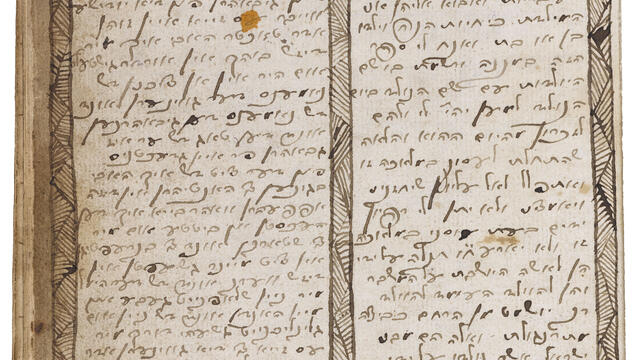

The famous and the obscure, women and men, in epitaphs and private letters, ethical wills, cookbooks, and religious reflections, all reflect aspects of Jewish life in a period of great transition.

The genre of life writing can be thought of as snapshots in words, glancing testimonies to Jewish lives. Although first-person accounts are mediated in multiple ways, excerpts featured in the Posen Library provide us some insight into what it meant to live, and to live as a Jew, in this period. The famous and the obscure, women and men, in epitaphs and private letters, ethical wills, cookbooks, and religious reflections, all reflect aspects of Jewish life in a period of great transition.

The literary genre we call autobiography is one of the signal innovations in this period among Jews across the spectrum. The examples in the Posen Library include many accounts that chart the development of the self; an individual’s coming of age; his or her realization that the self is formed, in positive and negative ways, by the culture into which it was born; and revelations about the inner journey of the self to become the character who writes. In particular, the self-conscious use of the narrative of a life came into its own as a signature of Enlightenment writing and moved quickly from the European world into Jewish literature.

While many Jews continued to write about their private lives in traditional modes, in letters, travel accounts, and rabbinic introductions, the maskilic (Jewish Enlightenment) autobiography in both Western and Eastern Europe became a virtually formulaic literary genre in which writers depicted, often with humor and pathos, the journey from childhood into adult awareness as parallel to their awakening out of the world of backward and superstitious traditional Jewish life to one of reason and beauty. Haskalah writers targeted the one-room schoolhouse, its boorish teachers and exclusive emphasis on Talmud study, as a failed pedagogical system. They skewered the traditional system of arranged marriages at a young age as contrary to nature and lampooned the general level of ignorance, even as it served as backdrop for their emergence into the light of reason.

Just as the individual figured in writings about the self, so, too, did the genre of biography and admiring hagiography arise in this period. Thus, the philosopher Moses Mendelssohn’s acolyte wrote about his life, and Hasidic followers wrote about their masters. Ostensibly worlds apart, the two movements shared a literary genre that elevated the exemplary life of a leader.

Life writing includes far more than formal narrations of a life in history. It includes every genre of writing that reveals something of the individual life: letters, diaries, and reminiscences of every kind. Jews plied every trade, from the expected (peddler, teacher, homemaker, midwife) to the surprising (Civil War soldier, pugilist, wine merchant). From wealthy merchant slaveholders to the starving and destitute, Jews around the world belonged to every class and expressed something of their lives in their written legacies. Learned philosophers poured out their souls in their personal correspondence while boxers recalled learning their art and women wrote about keeping house on the American frontier. Salon hostesses in Berlin and Vienna, brilliant conversationalists who broke social and class barriers by inviting people of every background into their homes, agonized over their tortured decision to convert out of Judaism. A superb rabbinic scholar erupted in incredulous fury when someone proposed a new match for him shortly after the death of his beloved wife. (Not to worry, dear reader: he recovered and had nine children with the next wife.) Each excerpt presented here provides us with a distant glimpse of the contours of a unique life, a Jewish life, at once greatly removed from our time, yet always human and somehow familiar.