Jewish Culture Confronts Modernity

Between 1750 and 1880, Jews were at the forefront of literary, visual, material, musical, and intellectual culture, introducing new techniques, innovative approaches, and fresh ways of looking at the world.

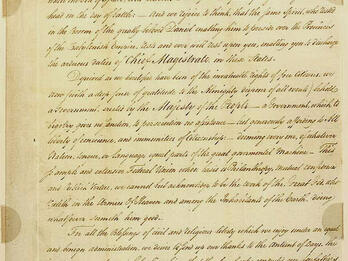

All of us who were still children thirty years ago can testify to the incredible changes that have occurred both within and outside us. We have traversed, or better still flown through a thousand-year history.

—Isaac Markus Jost, 1833

All aspects of Jewish culture underwent profound changes in the period between 1750 and 1880. The Posen Library contains sources that attempt to illustrate the trajectory of these transformations, telling the tale of a people who refused to sit on the sidelines while others did the work of culture, be it literary, visual, material, musical, or intellectual. There is virtually no field of human culture in this period in which Jews only participated enthusiastically; they often pioneered, introducing new techniques, innovative approaches, and fresh ways of looking at the world.

Most often, Jews were able to do this out of the deep wellsprings of Jewish identity and creativity itself. It is no exaggeration to claim that the very concept of a Jewish culture that was not primarily religious arose and was articulated first in the period 1750–1880. A truly Jewish total culture that was secular at heart while incorporating some traditional elements did not come to fruition until the advent of Jewish nationalisms (Zionism and diaspora nationalism), which lies outside of this period. What we have before us is a more inchoate and, in some ways, more interesting picture.

The breakaway from traditional patterns took place both in the form of an embrace of non-Jewish cultural idioms and forms, on the one hand, and in the conscious reshaping of Jewish traditional culture into something modern, on the other. Both of these movements are in full evidence in this period. They are intertwined and cannot, and ought not, be easily separated. Often the same artist or writer who made his or her mark in a fully neutral vein also pioneered new modes of representing aspects of Jewish culture. The cultural production of Jewish women and men was often distinctive and original because they were among the first Jews to participate creatively in their fields. This allowed them to bring fresh perspectives into the larger culture. Simultaneously, their efforts remade the very concept of Jewish culture.

Thus, the Posen Library does not include only material that looks or sounds “Jewish,” however that might be defined. To the contrary, it attempts to represent the full range of cultural creation by Jews regardless of whether such expressions contain identifiably Jewish content. As Richard I. Cohen writes with great insight, “Artists were so involved in their own radical break with Jewish traditional society and pattern, so concerned with coming to grips with the new surroundings into which they had been thrown [ . . . ] that much time was needed before a return to the past could be contemplated.”1 Even when writers and artists “returned” to a Jewish past, it was not the same as the primal and original engagement. In the words of Ammiel Alcalay, “The ‘Jewish’ world depicted becomes just that: subject matter, and not the very material of a way of life that is simply practiced from within.”2

If there is one thread that connects the multifarious entries in the Posen Library collection for the period 1750–1880, it is the sense of great possibility and openness. In some parts of the world civil barriers to equality before the law had begun to fall, Jews of the West had finally been granted citizenship, and others believed they would soon follow suit. Jews not only ventured into the world around them but also allowed the world to penetrate their thinking, their dreams, their very definitions of self, in ways they had scarcely done before. In places with large concentrations of Jews, the Jewish population continued to face hostility and prejudice in this period. The period closes just before some of the worst depredations of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries were unleashed with violent fury upon the world in general and on the Jews in particular. Thus, this period was one of creativity borne aloft by hope, a sense that the gates of the broader world of culture were finally opening to Jews, that their voices and their contributions could be judged on the basis of merit alone. European Jews embraced the opportunities with dazzling results.

Jews and Empire

Jews living in the Ottoman Empire, whether in North Africa, the Middle East, or the Balkans, encountered European culture in a far more complex set of circumstances. Just as Western powers spread their imperial message through their culture, their Jewish citizens, newly acculturated themselves, attempted to “enlighten” their indigenous coreligionists in colonial and semicolonial contexts. The synthesis of cultural strands they wove is multilayered and complex. Jewish culture in the Ottoman Empire in the nineteenth century emerged newly invigorated, drawing on the Middle Eastern and Iberian cultures to which it was heir. As European states expanded their footholds within the Ottoman Empire, growing numbers of European merchants settled in the empire, missionaries traveled its length and breadth, and scholars took to the study of its languages and texts.

The effect of Westernization coupled with new avenues for professional advancement changed the face of Ottoman Jewish culture. Although the political and economic fortunes of Jews in Islamic lands declined in the eighteenth century, the classes of merchants whose services were necessary for the Europeans seized the opportunity to advance. They became translators, intermediaries, and agents for European interests. They supported European-style education and vocational training for Jews. French Jews established a vigorous defense organization, the Alliance Israélite Universelle, in 1860 to protect the interests of Jews. This organization established a chain of schools that sought to intensify the Westernization process, opening a rift between Europeanized “francos” and native Jews, who often held different legal status and cultural positions. These developments ultimately accelerated the cultural gap between Jews and local Muslims in much of North Africa and the Middle East.

During the period between 1750 and 1880, Jews lived in and between a changing cast of ambitious empires built at the expense of weaker empires, whether neighbors or distant colonial outposts. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth fell prey to its expanding imperialist neighbors, as Russia, Prussia, and Austria partitioned it out of existence in the last decade of the eighteenth century. As a result, the three-quarters of a million Polish Jews were divided among these empires, with the largest number falling to the tsarist Russian Empire. The Ottoman Empire, which predated all of these, began to sustain serious losses during this period, although it continued to rule over much of the Middle East, North Africa, and southeastern Europe throughout the period. The sun never set on the British Empire in this period; the ambitious French Empire expanded its borders to distant shores, touching Egypt and conquering Algeria by 1830. The Netherlands, Spain, and Portugal engaged in empire building across the Atlantic and in the Pacific, gaining and losing colonies in Asia and the Americas. Cultural and linguistic shifts accompanied each political turn in every one of these polyglot and multiethnic societies. Jews, never a majority and often a marginal minority, were often caught between the shifting borders. Their decisions regarding choice of language, which to write in, or to educate their children in, often had serious political ramifications. What might seem like a curricular preference could easily lead to alienation or even charges of treasonous departure.

When the partition of Poland brought the region of Galicia under Habsburg Austrian rule in 1772, a great population of Yiddish-speaking Polish Jews found themselves virtually overnight in a very different cultural sphere: German-speaking, Enlightenment-influenced, and Catholic rather than Christian Orthodox. Under Austrian influence, many Galician Jews adopted German language and culture, which Poles regarded as a shameful and traitorous choice, and Jewish culture increasingly came under Enlightenment influences, parallel to that of modernizing German Jews. A far greater rupture befell the Polish, Lithuanian, and Ukrainian Jews whose fate was to come under Russian rule. Largely restricted to the western frontier that came to be called the Pale of Settlement, the population of predominantly Yiddish-speaking Jews suffered the vagaries of an inconsistent and ambivalent government whose policies shifted among measures designed to forcibly integrate, convert, or segregate them.

Beyond the political transfers triggered by imperial brinkmanship, another ubiquitous change supported the emergence of new cultural forms. In the period under consideration, Jews underwent demographic shifts of staggering proportions. In some parts of the world Jewish populations declined while in others, the numbers soared. Particularly noteworthy is the growing number of cities in the Russian and Ottoman empires whose Jewish populations accounted for as much as one-third of the overall population. As Jews left the countryside and small villages for expanding cities, this had a great effect on their cultural production. The urban bustle, the proximity to stimulating images and ideas, the public sphere offered by cafés, parks, boulevards, and taverns in which to exchange views and learn about the lives of others—all these nurtured multiple forms of cultural productivity, both intensely Jewish and decidedly not.

Religious and Communal Transformations

The period between 1750 and 1880 spans the two most foundational events in U.S. history, the American Revolution of 1776, which liberated the states from British colonial domination, and the Civil War, of 1861–1865, which was fought to unify the states and abolish the way of life made possible by slavery. As Jonathan Sarna and Jonathan Golden say of the American Revolution, it was a turning point not only in world and U.S. history but in Jewish history as well: “Never before had a major nation committed itself so definitively to the principles of freedom and democracy in general and to religious freedom in particular. Jews and members of other minority religions could dissent from the religious views of the majority without fear of persecution.”3 The years between and around these events saw two primary waves of Jewish immigration to the United States, although no group was exclusive in either period. The first small group of North American Jews arrived as refugees from Recife, Brazil, in 1654. When Brazil fell to Portugal, these Sephardic Jews fled the Inquisition and headed for greater religious freedom in New Amsterdam (later, New York). Others soon followed. The Sephardic pioneers profoundly shaped public Jewish culture through the early nineteenth century. The second wave (ca. 1820–1880) is loosely dubbed the “Central European” migration. Jews fleeing Europe often came from socially disadvantaged classes, and adjusting to the opportunities of America took time. Women often ventured beyond home and hearth to help with family finances and ultimately found independent voices in public forums. This created a unique space for cultural production that differed in context and content from the European models.

At the outset of the period, most Jews lived within the framework of religious tradition. Religion constituted one of the primary components of Jewish identity and the central modes of Jewish cultural expression. With some notable exceptions, this had not changed profoundly since the medieval period. Similarly, most Jews lived within Jewish communal structures that governed many aspects of their social lives and civil status. By the end of the nineteenth century, the pillars of these institutions were greatly weakened; in parts of the world they were completely shattered. In the West, as Jews were socially integrated and legally emancipated, community lost its holistic and authoritative structure. In Russia, particularly under the reign of Tsar Nicholas I (1825–1855), conscription of Jewish boys into Cantonist camps at very young ages, and the cooperation of Jewish leaders in providing recruits, made Jews fear and distrust the Jewish communal elite. Although for some Jews breaks with the past occurred almost overnight, for others changes took place far more gradually and imperceptibly. Improvements in the standard of living in the West toward the beginning of the nineteenth century also spurred changes in the cultural lives of Jews. A prosperous middle class that included lawyers, doctors, entrepreneurs, and civic leaders soon emerged as a new type of patron of the arts. In Eastern Europe, Hasidic Jews supported lavish courts for their leaders while deeply traditional Jews continued to support hundreds of yeshivot and study halls where rabbinic scholarship was advanced.

In many parts of the world, as cultural endeavors by Jews were no longer rooted in religion, Jews experimented with different definitions of Jewish identity. The quest to find a positive Jewish identification that was not exclusively religious yielded fascinating and varied new results. This was a period of constant transformation. For some Jews, this period was marked by the transition into modernity, for others into a new form of colonial rule, and for others yet, a growing confidence that they could put down roots in lands of relative civic equality and freedom. Many of those who steadfastly championed religious tradition could nevertheless be seen as making conscious religious and cultural choices within the marketplace of competing identities, options that were themselves creations of modern times.

Jews and Non-Jewish Culture

The dizzying array of choices about their very identity and the means of expressing it, as well as continuing hostility to Jews and Jewish culture through the nineteenth century, propelled some Jews to abandon their Jewish identities entirely. For others, social, religious, and cultural bonds to Jews and Judaism diminished over the course of generations, leading to a process that Todd M. Endelman has called “drift and defection.”4 This happened frequently enough that conversion out of Judaism in this period can be seen as one of an array of choices made by Jews, one that characterized the Jewish experience in this period no less than intense attachments. Religious conversion to another faith generally led to a historical dead end for an individual’s progeny as members of the Jewish people.

The Posen Library nevertheless includes the contributions of converts if their work could be seen as having been nourished in some way by their Jewish background. The poet Heinrich Heine, statesman Benjamin Disraeli, composer Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy, salonnière Rahel Varnhagen, Russian schoolteacher Jacob Brafman, and founder of communism Karl Marx provide some of the more renowned examples of this category. In many cases converts knew and interacted with one another, sometimes over several generations, and many placed the struggle to define themselves at the center of their creative work. Familial ties ran strong in convert families, who often socialized with one another both out of preference and as a result of subtle discrimination. Their transformations of Jewish identity and the allusive references to it allow us to include such figures not just because of the accident of their birth, but also because their Jewishness remained an elemental and enduring aspect of their lives, their art, and their work.

Developments over the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries provided more than new opportunities for Jewish encounters with non-Jewish cultures: they completely transformed the fields on which these interactions played out. The traditional templates of Jewish culture as existing within the framework of majority-minority relations, of those who belonged and barely tolerated aliens, receded. Instead, a growing Jewish self-consciousness emerged, with new definitions and articulations of the self. Where premodern life writing by Jews located the self firmly within the communal sphere, Western, and later Eastern European Jewish autobiography emphasized the individual’s break from community and tradition.

Jews embarked on this odyssey along utterly different pathways depending on national community, geography, and individual proclivities. For some Jews, this passage meant mobility from village to urban settings, from economic margins to bourgeois prosperity, from old world to new, and in some parts of the world, from pariah to civic equal. In Western Europe, the demise of the kehilah (structured Jewish community) and its traditional authority, largely accomplished over the course of our period, meant the disappearance of a holistic Jewish life and culture that did not depend on the world outside it for validation. It opened the way for Jews to embrace the culture of the majority directly and consciously, and to do so in ways that ranged from the superficial to the profound, from head coverings, facial hair, and dress style to social, linguistic, economic, and occupational choices. Introduced to European philosophy, scientific and intellectual achievements, art, music, and theater, Jews immersed themselves in, and soon mastered, these genres.

In nineteenth-century Russia, deep fissures characterized Jewish society. The vast majority of Jews became increasingly impoverished, with limited access to economic and educational means to improve their lot. Wealthier Jews migrated to St. Petersburg, where they lived like urban elites. The best of the Talmud scholars flocked to cities with famous yeshivot, as in Vilna, while a cadre of official rabbis administered to the religious needs of their often disenchanted flocks. By the second half of the nineteenth century, as the reign of Nicholas I ended, Jewish ideologues embraced multiple paths designed to bring Russia’s Jews to a more dignified existence.

In the Ottoman Empire, a different cultural pathway appeared. Within the Jewish court system traditional rabbinic leaders had to compete with state-supported (or appointed) rabbis. While state backing would appear to have strengthened these rabbinic courts, this was not the case. The rise of new “mixed” state courts alongside the existing Islamic and consular courts, where Jews also historically went to adjudicate various cases, made for a system of legal pluralism that weakened the hold of the Jewish courts over Jews in the empire. Nevertheless, religion resided far more closely with features of modern Western life, and this is reflected in the cultural production of the period. The comfortable accommodation of state, religion, and culture in the Muslim sphere contrasted with the antagonistic relationship of state, religion, and culture in the Christian world.

New models of Jewish leadership emerged in this period: maskilic intellectuals, Hasidic rebbes, writers, artists, and a secular intelligentsia. They shared a rejection of the traditional model in which a combination of piety and rabbinic scholarship, with emphasis on the latter, formed the primary basis of authority. By overturning models of leadership, Jews challenged long-standing traditions of hierarchical values in Jewish society.

Two central themes intersect at the very foundations of the Jewish experience in this period. In the West they are traditionally termed Enlightenment and Emancipation. The Posen Library construes these concepts in the broadest way possible, such that they embrace the Jewish experience without borders. The former term refers here to engagement with the larger culture, the adoption of new modes of Jewish self-definition, and a reconfigured relationship to the majority culture. The strong and varied forms of resistance, in many parts of the Jewish world, to such engagement were inextricably intertwined with these developments.

The term emancipation refers broadly to the constantly shifting relationship of Jews to their states and to the societies of which they formed an integral part. This period sees the emergence of new cultural, religious, and political movements, as well as new individual identities, representations, and expressions of the Jewish self vis-à-vis the community and within the non-Jewish world. These movements and choices often appeared in innovative configurations that had little precedent in Jewish culture. They alternately embraced, rejected, or revised the Jewish elements that emerged from the crucible of self-examination, public deliberation, and the private agony of modernization.

This period concludes, then, on a high note. The most distressing turns in nineteenth-century European history, Russian pogroms, and the Dreyfus affair in France had not yet occurred. Their effects, including mass migrations to the United States, Canada, and Latin America, and the founding of Zionism, were not yet imaginable. The Ottoman Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the tsarist Russian Empire still governed their subjects. The key to entering the past sometimes resides not in remembering but in forgetting. If we are to enter the world of our subjects, we must forget what we know came “after.” What may seem to be fragile victory from a contemporary perspective appeared to the Jews of the nineteenth century as inexorable progress. They seized opportunities regardless of how hesitantly offered and turned them into achievements of enduring value, deep humanity, and surpassing beauty. What opens before the reader in this period is a panorama of hope and of passion for the world.

Notes

Richard I. Cohen, Jewish Icons: Art and Society in Modern Europe (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 158.

Ammiel Alcalay, After Jews and Arabs: Remaking Levantine Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993), 213.

Jonathan D. Sarna and Jonathan Golden, “The American Jewish Experience through the Nineteenth Century: Immigration and Acculturation,” National Humanities Center, Brandeis University, http://www.bjpa.org/Publications/details.cfm?PublicationID=4067.

Todd M. Endelman, “German Jews in Victorian England: A Study in Drift and Defection,” in Assimilation and Community: The Jews in Nineteenth-Century Europe, ed. Jonathan Frankel and Steven J. Zipperstein (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 57–87.