Women’s Farming Schools Abroad: Travel Notes and Impressions

This trip abroad to study the function of women’s agricultural schools was accomplished via a partnership of the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce with the Humanitarian Society, which, at the end of last May, approving the approach and intents of the first Italian women’s agricultural school founded in 1902 by Comiato of Milan, sanctioned the contribution of 10,000 lire to found a completely analogous institution and 2,000 lire toward its annual budget.

Thus, the cycle of my pilgrimages to women’s agricultural schools concluded and the work of thinking about what else to consider has commenced, beginning with my research on directorial parameters useful to our position.

We in Italy have done very little in comparison to small Belgium for the instruction of woman, called by destiny, to life in the fields, little or nothing to make it conscious and modern, and nothing to draw from her—an even rougher force—the lively energies of the environment that surrounds her. And this truth, put before the concept of the importance of agriculture in our country, generates a profound discomfort.

We have the duty to repair the damages done by our negligence; to study the question seriously and to begin without delay—armed with great perseverance—the experiments that will show the most practical way, and the means most likely to achieve this scope, in harmony with the needs and various characters of the diverse regions of Italy.

It seems to me that we can no longer postpone founding practical and professional schools, in which the woman truly learns to be a woman, and prepares herself for familial duties, where very often, for tyranny of circumstances, she is called to the function of economic protection of the weakest individuals, whether these are younger siblings, the elderly, or grandchildren, when they are not able to care for themselves.

Thus, if there is a class that today is far away from having educational institutions that meet their own needs, it is precisely the countrywoman, women who remain ignorant, or those who fill themselves with the superficial culture of their associations, or even those who desert the nest, especially if the need drives them and intelligence is not lacking: they are attracted to the city, where work and study can assure existence. But the city makes them victims; and anyway, the exodus from the countryside, though impoverishing, has the natural consequence of excessively thickening the population in its city centers, whose harms are lamented unanimously, by all economists.

I believe—and I allow myself to say so—that this question of the agricultural education of women must be considered with two points of view, likewise taking into account the various modes in which the property of our peninsula is distributed.

How I wish many schools for daughters of farmers, proprietors, and all of those middle classes with rural interests would arise, schools on par with those for male farmers, with both distinctly professional and domestic characters, a kind of ménagères agricoles of Belgium, which confers a diploma that gives access to employment in large and small agrarian industries. And like those, I would also like to see schools of a more humble nature arise, in the form of temporary sections and the so-called moveable schools of Belgium: [schools as] instruments of agriculture that arrive where the need is most felt, those places where light does not reach, because no one, not even out of desperate material conditions, would move to find it. So while the first type has been attained—in the awakening of agricultural and national life; channeling nascent female activities in new ways; avoiding crowding the most frequented streets, procuring a great hygienic advantage for many young women; contributing efficiently to forming, with that hard-working culture, the class of women in charge of the countryside, who fight against prejudice and ignorance—the second more modest kind of agrarian school will introduce poor country families to the notions that they are capable of turning around their profits and their health, concepts useful to improving the functioning of a house, adding comforts, a smile.

So that, with different paths, the two didactic forms will lead to the same goal and will complement each other. But one cannot say that the itinerant academics have already mastered the second curriculum; the traditional lecture, not illustrated by the current experiment, can no longer hold its place—especially for an uncultivated female public—rather, they need the direct action of the teacher who explains and demonstrates, forcing the rational aspect so that it is understood and becomes habit.

There must be similar schools, if not one for each province, then at least for every group of provinces; in the north of Italy especially for sericulture and cheese production, and in the center and in the south for floriculture, pomology, and horticulture. The cost being limited, one could certainly attempt to test in more parts—the government, provinces, agrarian commissions, and municipalities will all contribute.

In Milan, the Humanitarian [Society], which intends in its very essence beneficial prevention, will see, I hope, to the adoption of this proposal validated by the foreign example.

And how many colleagues, educators in Italy who are ill-equipped, badly directed, seedbeds of those displaced, could ultimately be reduced to the agrarian type!

This idea was suggested to me in a letter from R. Prefetto from the province of Arezzo who “would like to change a female orphanage into a female agrarian school, which would be a providence in this eminently agrarian region, where all proceeds with empiricism, without rational concepts.”

And I also know that Comm. Pecile, now Mayor of Udine and President of the Friulian agricultural association, is working to add a female section to the agrarian school of Pozzuolo, and to persuade the council directed by Orfanatrofio Renati and by the Micesio Institute to found two schools for practical agriculture.

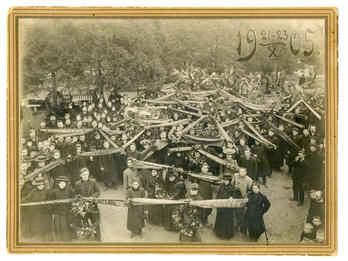

The idea is spreading and will be realized. From the small Niguarda, where the first female school of practical agriculture holds its modest seat, a vibrant impulse began, a seed that was thrown but was not yet germinated. [ . . . ]

The combination of the promised the amount of 10,000 from the Umanitaria [Humanitarian], the aid of 500 lire from the province, and the 100 lire from the Office of Commerce will not suffice to equip the school with a boarding school for those who come from outside and for materials necessary to initiate special courses. This, as of now, needs an economic miracle and good faith, for in its fourth year of life it lacks the indispensable means for its development. The Ministry of Agriculture will give three-fifths of the law when two-fifths of the annual balance and capital of the foundation are collected.1 Milan, center of a most excellent agricultural region, can no longer be deaf to this call; it cannot, nor should it, renounce the noble pride of being mother of vitality, an example of patriotism. Whence I draw happy wishes from my vows, and faith in the future, that the efficacy of women’s work in the social and material progress of life in the fields will not fail.

Milan, October 14, 1905

Aurelia Josz

Notes

[Unclear. Presumably the Ministry of Agriculture was required by law to provide three-fifths of the operating budget after two-fifths were obtained elsewhere.—Eds.]

Credits

Aurelia Josz, Le scuole femminili agrarie: All’estrero [Women’s Farming Schools Abroad: Travel Notes and Impressions] (Milano: 1905), pp. 3, 34–38.

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 7.