Jewish Writing in the Postwar United States

Jewish American writers gained mainstream success writing about immigrant experience, assimilation, and the trauma of the Holocaust.

Life Writing

Jewish life writing also underscores the special character of the United States, a country that offered Jews unprecedented opportunity not only to prosper but also to redefine themselves and to calibrate the fine balance between personal ambition and collective identity. In the aftermath of the Holocaust, this kind of life writing exemplified the centrality of American Jewry. Immigrant memoirs describe choices, some seemingly quixotic, but others focused on future prospects.

In America, Jewish life writing could also be more frank and uninhibited in comparison with Europe. Judd L. Teller’s description of “Goyim,” violent gentiles who terrorized Jews in his hometown in Poland, showed an openness and self-confidence that might have been less apparent in his birthplace. In the aftermath of the Holocaust, it was also in America—a gathering place of immigrants—that life writing could evoke and recenter memories of different, shattered Jewish worlds, in part by drawing on common American experiences of immigration. Leon Sciaky’s Farewell to Salonica: City at the Crossroads, Jehiel Isaiah Trunk’s Poland: Memoirs and Scenes, and Joseph Buloff’s From the Old Marketplace pictured their lost Ladino- and Yiddish-speaking homes through the lens of personal experience: place, streets, childhood games, and above all, the bedrock of family.

Precisely that interplay of memories anchored in family and place refracted through a new prism of postwar sensibility made Alfred Kazin’s 1951 A Walker in the City such an important example of American life writing. This long “prose poem” was a striking departure from familiar stories of immigrant poverty, squalor, and despair. Instead of naturalistic determinism, it stressed freedom and possibility. Poverty marked Kazin’s family but it did not prevent his parents from creating a home. And it was from that home, anchored in the family kitchen, that Kazin set out on his walks through the city, discovered the joys of literature, and exulted in his growing mastery of language. The slum did not destroy Kazin but propelled him forward and outward; through writing and memory he could reimagine his world and remake himself.

Literature

The late 1940s, when Kazin was writing A Walker in the City, was a liminal moment in the development of Jewish fiction and poetry. A new generation, mostly raised in immigrant, Yiddish-speaking homes came into its own just when American literature stood ready to embrace Jewish writers, Jewish themes, and the cadences of Jewish writing in English, not as examples of exotica, parochialism, or immigrant culture but as a mainstay of postwar American culture.

Just a few subway stops away from Kazin’s Brownsville, Jacob Glatstein (“Without Jews”), Kadya Molodovsky (“God of Mercy”), and Aaron Zeitlin (“To Be a Jew”) were mourning the Holocaust in some of the most powerful poetry ever written in the Yiddish language. Yiddish literature was still a closed book to American Jews, and Holocaust memory still defined and segregated by the barriers of language. But by the early 1950s, the first glimmer of change appeared: Saul Bellow’s translation of Isaac Bashevis Singer’s “Simple Gimpl,” a brilliant tale of how in an immoral and wicked world, gullibility and purposeful naïveté were the only foundation of honesty and integrity.

Many factors shaped the Jewishness of this generation of writers and critics: exposure to an immigrant culture that foregrounded Jewish memory and difference, the lingering impact of Yiddish speech, a tradition of secularism and moral commitment that sought new outlets after the eclipse of 1930s leftism, and an uneasy relationship with postwar bourgeois American Jewry.

One of the most touching postwar voices was Grace Paley’s. A sense of “at-homeness” in America, so different from Europe, emerges in her short story “The Loudest Voice,” which transforms traditional, dangerous reminders of Jewish marginality—the story of Christ’s birth and crucifixion—into a buoyant description of the insouciance and self-confidence of a young daughter of Jewish immigrants. Shirley Abramowitz’s loud voice lands her the best role in the school Christmas play, the voice of Christ. Far from feeling inferior or out of place, Shirley, encouraged by her immigrant father, confidently channels Jesus’ words in her own cadence as other Jewish children enact the nativity scene.

But if Shirley Abramowitz was a picture of self-confidence, Neil Klugman in Philip Roth’s Goodbye, Columbus or Alexander Portnoy in Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint revealed a more complex picture of Jews in midcentury America, with its fraught transition from immigrant poverty to material affluence, from the old ethnic neighborhood to leafy suburbs. Jews had arrived, but to what? Some American Jewish writers, like Herman Wouk in Marjorie Morningstar, regarded this new suburban frontier with optimism, with opportunities for Jewish continuity and for better family life. In contrast, Roth, who had little use for the communitarian pieties of the organized Jewish community, deftly explored the fragile vulnerabilities of a new generation of American Jews who were too American to be comfortably Jewish and who felt too Jewish to be totally American. Materialism, dysfunctional families, suffocating Jewish mothers, and sexual neuroses were all fair game for Roth’s satire, condemned by some as deplorable self-hatred, lauded by others as brilliant literature.

The Holocaust

It goes without saying that the Holocaust loomed large in postwar American Jewish culture. Susan Sontag remembered her first reaction to photographs of the concentration camps:

Nothing I have ever seen—in photographs or in real life—ever cut me as sharply, deeply, instantaneously. . . . Something was broken. Some limit had been reached, and not only that of horrors; I felt irrevocably grieved, wounded, but a part of my feelings started to tighten; something went dead; something is still crying.1

In some of their most powerful writing, Philip Roth (“Eli, the Fanatic”) and Bernard Malamud (“The Last Mohican”) expose the psychological brittleness of anxious, insecure assimilated American Jews in their encounters with Holocaust survivors. These encounters triggered deep feelings of guilt and even identification.

In a different vein, Saul Bellow’s Mr. Sammler’s Planet, which vented his outrage against the self-indulgent and overly permissive counterculture of the 1960s, also presented, through Sammler the Holocaust survivor, a deep moral message rooted in Jewish culture: the imperative of “meeting the terms of one’s contract.”

The newfound salience of American Jewish writers was exemplified by the success of Saul Bellow’s Herzog, an unmistakably American novel, despite the fact that most of the characters were Jewish. The brilliant portrayals of New York and Chicago, the large tableau of secondary characters, the comic tension between intellectual brilliance and emotional failure—all serve to make Herzog much more than a “Jewish” novel.

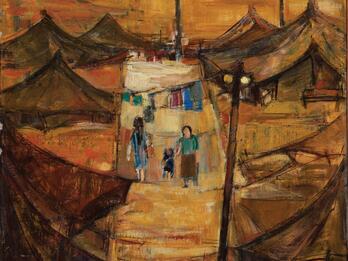

This was a time of trauma and rebirth, of despair and soaring self-confidence. For the most part, with the exception of communist Europe, these years were “good for the Jews.” Indeed, one need only look at the major changes in the depiction of Jews in photography and the visual arts to understand the incredible transformation of the Jewish condition that took place. In 1939 and the early 1940s, Jews were commonly portrayed as poor and struggling, as refugees dependent on the goodwill of others. By the end of this period, such images largely disappeared; in Garry Winogrand’s photographs, for example, Jews are middle-class Americans. This is not to say that by 1973 trauma and worry had disappeared from Jewish life. The Yom Kippur War ended the “heroic era” of Israeli history and ushered in a sober realization that Israeli power had stark limits. In the United States, the pace of assimilation and intermarriage began to quicken, as did growing doubts about the future of the postwar “golden age” of American Jewry. But compared to the dangers of 1939, these worries were mere trifles.

Notes

Quoted in Edward S. Shapiro, “World War II and American Jewish Identity,” Modern Judaism 10 (1990): 65–84, 74.