Early Modern Trade and Mercantilism (1500–1750)

International trade drove Jewish mobility during the age of mercantilism, as Jewish merchants formed wide commercial networks and partnerships and developed cosmopolitan attitudes that facilitated civic inclusion.

Not only persecution and expulsion, but—and this was the case for the medieval period as well—a variety of social, economic, and cultural factors stimulated Jewish geographical mobility. This era has been called the age of mercantilism, and involvement in international trade encouraged Jewish merchants, both individuals and groups, to undertake long journeys by sea and by land. At the same time, being dispersed among many countries and continents gave them advantages over merchants belonging to other ethnicities. Most Jewish international merchants were part of the Western Sephardic diaspora. This diverse group was made up of, on the one hand, Jews, many of whom were descended from those expelled from Spain or were Marranos who had returned to Judaism, and on the other hand, former Jews, converts from Judaism who lived in Spain, Portugal, and elsewhere in Western Europe and the Americas. Family ties, ethnic connections, and common financial interests of Jews and New Christians in this diaspora usually overcame tensions caused by religious differences, allowing them to form wide-ranging and complex commercial partnerships.

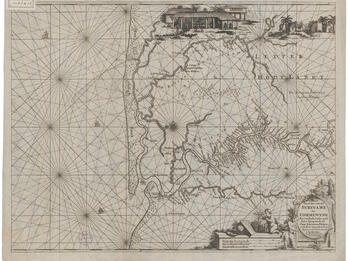

One example among many: in the seventeenth century, the Mediterranean port city of Livorno became a vibrant and flourishing cosmopolitan center. After the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Ferdinand I, gave Jews permission to live in Pisa and Livorno in 1593, the embryonic Sephardic Jewish community played a central role in making it one of the most important ports in the Mediterranean. The firm of Ergas and Silvera, owned by Portuguese Jews, exemplifies the dynamic economic activity that took place there. Active between 1704 and 1746, the firm exported to India, by way of London and Lisbon, coral beads that had been manufactured in Livorno. In other words, Jews were involved in international trade even with countries where Jews were forbidden to live. The historian Francesca Trivellato coined the term communitarian cosmopolitanism to characterize the experience of the Sephardic merchants who were able to meld multiple traditions and to cooperate with non-Jewish merchants within the framework of a corporatist society.

Port Jews

Historians introduced the concept of Port Jews to highlight the economic, social, and cultural characteristics of Jews living in port cities on the Atlantic and the Mediterranean coasts, especially from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century. These Jews have been described as having a flexible attitude toward their religion and observance of the commandments, and as being, in general, more open to the surrounding culture and new ideas. Indeed, a tolerant, pragmatic, and cosmopolitan atmosphere seems to have characterized most of these centers. Strikingly, the tendency of the Port Jews to acculturate appears to have encouraged the authorities to offer civic inclusion to them sooner than they did elsewhere.

Of course, there were more than a few differences among the Jewish communities in Salonika, Izmir, Amsterdam, Livorno, Hamburg, Bordeaux, and London, and in the political and social status of the Jews in each of these port cities. However, despite their differences, some elements in their culture and relation to the Jewish tradition were common to all of them. For example, Port Jews were usually capable of communicating in a number of languages, and they were the first to be exposed to enlightened ideas, both because of their connections with booksellers and also by virtue of the contacts they formed with exiles from other countries. As Lois Dubin writes, “Merchants were often boundary-crossers, and communities of merchants in trade diasporas were often cross-cultural brokers: as they brought goods from one zone to another, they also mediated between one culture and another.”1

Notes

Lois C. Dubin, “‘Wings on Their Feet and Wings on Their Head’: Reflections on the Study of Port Jews,” Jewish Culture and History 7 (2004): 14–30, 15.

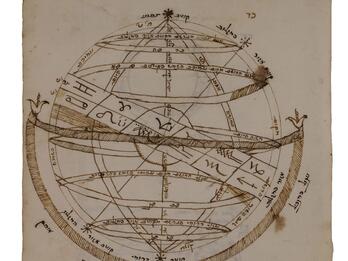

![M10 622 Manuscript, probably from Ukraine]. Manuscript probably from Ukraine, c. 1740 with a broad collection of practical kabbalah and mystical magic. Facing page manuscript arranged vertically with Hebrew text in the shape of a figure wielding two long objects.](/system/files/styles/entry_card_sm_1x/private/images/vol05/Posen5_blackandwhite166_color.jpg?h=cec7b3c9&itok=Sz6u21MQ)