Speech: Against Antisemitic Persecution

Persecution because of a person’s religious observance is reprehensible, even despicable, though still somewhat understandable. What is understandable—I am not saying: justifiable—is that zealots who imagine that their doctrine is the sole ultimate truth, that salvation, of need through coercion, would have those of other faiths accede to it. What is temporary earthly torment compared with eternal heavenly bliss? This was generally the view of the men of the Inquisition. Buckle writes: “In Spain, persecution of heresy was regarded as a duty.”1 Llorente,2 the greatest historiographer of the Inquisition and also its harshest critic, the man who saw the secret documents of the Inquisition with his own eyes, did not once deplore the ethics of the inquisitors. While he eschews the gruesome nature of their actions, he has been unable to deny that their intentions were sincere. Those who supported the barbaric institution of the Inquisition were not hypocrites but zealots.

Hypocrites, on the other hand, although they invoke religious observance as a pretext for persecution, are in fact driven by racism and envy. Racism and envy, in fact, underlie the present Jewish question. It is treated as a social matter, even as a political one, especially in Russia, where the Jews are accused of disseminating revolutionary principles. There, however, the matter has a peculiar, rather singular nature. Racism and envy, dear sirs, are generally the modern version of nineteenth-century hatred of Jews. A few zealots merely invoke the Jewish question for the auxiliary purpose of compelling Jews to abandon their ancestral religion. [ . . . ]

Watchman, what has become of the night? Morning has come, but it is still dark. Renowned, acclaimed civilization of the nineteenth century, are you but an irony? That question inevitably arises, when in a country that calls itself civilized millions of people are treated—or rather mistreated—as vermin to be exterminated. This must be asked, given the outrageous uprooting and expulsion of the Russian Jews; atrocities that disgrace this nineteenth century and against which we protested on behalf of humanity. Such protest is appropriate here, in the Netherlands, especially in our tradition of tolerance, in our blessed land that welcomed the persecuted Jews, and where, under the care of our cherished House of Orange, our freedom is and remains sacrosanct. [ . . . ]

How can we eradicate antisemitism? What a difficult question! Presumably, it will always exist, because jealousy will always exist as well. Still, in my view, by reconsidering, we can do a lot to mitigate this. Above all, we must try to avert all jealousies great and small. We can do this by avoiding taking center stage too often or by calling excessive attention to ourselves by being very loud or agitated, keeping in mind that humility was the virtue most becoming to Moses. The Doctrine was given on Sinai, precisely on the lowest mountain. This shows that we thrive best in humility.

This definitely does not mean that we should cede our independence, our self-respect. No, where appropriate, we should have the courage to state openly, as Jonah did: I am a Hebrew, and I fear God in Heaven (Jonah 1:9). As for the higher principles, some pride behooves us—always modest pride, and the obsta principiis [resistance to encroachments] apply. Without advertising that we are Jewish, we should not be ashamed of being Jews. A German leaflet addressing the Jewish question attributes antisemitism in Germany chiefly to the lack of principles of those known as Salon Jews, who are ashamed of being Jewish, who want to Christianize themselves by adopting all conceivable and inconceivable names and by—at any cost—marrying among Christians, even those of low standing, while scorning their erudite and civilized coreligionists; Salon Jews, who in their yearning, to adopt a Christian veneer, even sacrifice their idiosyncratic Jewish humor; Salon Jews, who—writes a German author—“find [no] dowry too high,” as long as their daughter can wed an impecunious Christian lieutenant, wearing a few epaulettes, and would sacrifice their entire salvation for a baron son-in-law.

If we strike the right balance in that respect, and if this entails honesty and sincerity in daily practice, cultivating religious sense and civilization, among which we also include studying our magnificent history and religious scriptures, we will deprive the adversary of powerful weapons. It is up to the Jewish leaders of and educated Jewry in general, acknowledging and appreciating Israel’s excellent attributes, to mention some of its offensive properties, keeping in mind the words of Van Alphen: “It is a friend who tells me my shortcomings.”3 This will elevate the Jews and essentially civilize them. That way prejudice may be diminished, albeit slowly. This also does justice to the spirit of the wonderful global institution l’Alliance Israélite Universelle.

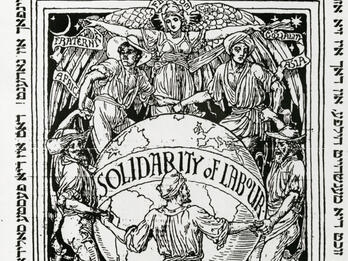

Elevating the moral standards of the wondrous historical people who course through world history as a wandering mystery, growing as the palm under pressure. Elevating the moral standards of Israel is surely the beautiful, noble goal of the Alliance, which connects Jews—from east to west, from north to south—to each other, by a bond of love, mutual aid, and solidarity. Many of those persecuted and exiled have now pinned their hopes on this highest humanitarian institution, which to them is a light, an anchor “and to which they extend their trembling hand.”

Many of the persecuted and exiled are in any case our own people; they are flesh of our flesh, blood of our blood. Like us, they come from the ancient people of Israel. They are connected to us by the same religion, by the same hope.

Notes

[This is an abridged quotation from Henry Thomas Buckle (1821–1862), History of Civilization in England (London: 1857), chapter 4.—Eds.]

[Juan Antonion Llorente (1756–1823).—Eds.]

[Hieronymus van Alphen (1746–1803), “De ware vriendschap.”—Eds.]

Credits

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 7.