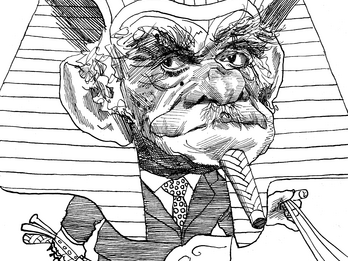

Sigmund Freud

To Freud, all forms of religious observance were foolish and superstitious. His wife Martha, on the other hand, took religion much more seriously, as her grandfather had been a prominent rabbi in Hamburg. It took Freud many years before he finally managed to persuade her to move away from her strict observance of orthodox Jewish customs. And, indeed, even as late as 1938 they were still carrying on a long-standing humorous serious battle over the issue.

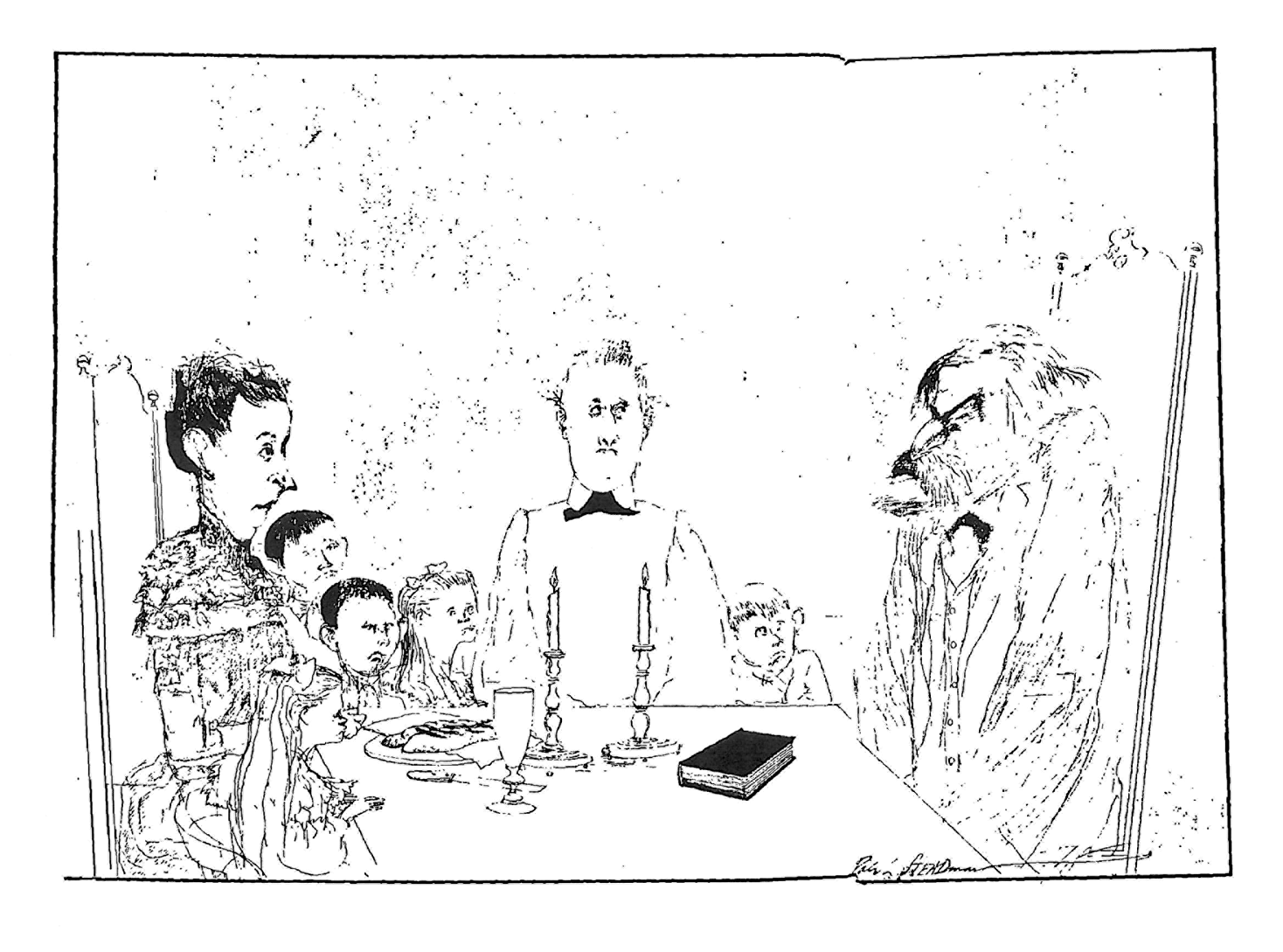

Here is a typical brisk interchange between them as Freud sits down to dinner one Friday evening, having had a particularly harassed day at the office. Minna Bernays, Freud’s sister-in-law, is seated between them. Freud speaks first:

“What the blazes is this?”

“You know perfectly well, dear. It’s the Sabbath.”

“But I thought we settled this years ago.”

“We did, dear. But the children are fascinated and they want us to celebrate it.”

“But haven’t you explained?—it’s merely the survival of some tribal neurosis!”

“Yes, dear.”

“One of the many outward signs of a collective superego!”

“I’m sure, dear.”

“Obsessional neurosis! Defending the tribe against incestuous wishes and the death wish against their father!”

“We know all that, dear. Now, will you recite the blessings or shall I? The children can’t wait to see you castr—er—uh—cut the challah. Collectively, that is.”

The laconic addition at the end of Martha’s last remark is a form of vague defensive condensation of all that has come before, bringing all of Freud’s pedantic statements back to earth, diffusing the psychic tension and making it possible for everyone present to relax back into normal family discourse. The situation is only a joke when one appreciates all the elements involved—rather as a playwright who is able to develop a remark into a joke by carefully constructing the situation into which he is injecting it. It is not the stuff of stand-up comics.

Credits

Ralph Steadman, illustration from Sigmund Freud (New York: Paddington Press, 1979). Copyright © 1979, 1997 Ralph Steadman. Used with permission.

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 10.