Reflexoens politicos tocante a constituaçāo da Naçāo Judaica (Political Reflections Concerning the Constitution of the Jewish Nation)

No matter what the body of the Nation, be it in the form of a kingdom or a republic, it comprises various classes of people; as for the nobles, who make the state blossom through commerce, increased coinage in exchange for manufactured items, they, after assembling large sums of money, will purchase offices, eminences, and business establishments, with which they will perpetuate these riches, in their families, reserving commerce for their second sons, or providing fine employment for them in arms or letters. Then comes industry and the mechanical trades, in which many people engage, who, not being obligated to any given person, are utilized by all and, by contributing to leisure and opulence, they will extract what is necessary from the superfluity.

This class, however, need not be very large, because one person can meet the needs of many, so that if the number becomes excessive, people will get in each other’s way.

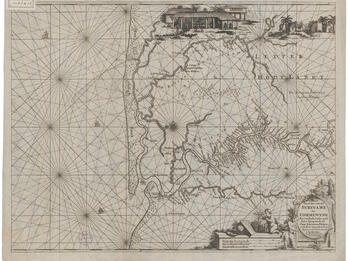

In addition, there are other diverse and innumerable occupations, for let us cast an eye on the number of people engaged in shipping,1 both in ship-building and seafaring. No fewer are engaged in the militia and what is lost therein. People are also engaged in agriculture, whose advantageous work absorbs countless numbers of people, and with all these outlets and these various occupations, they are still quite hapless and the object of public and private charity. For our purposes, one has only to observe that what in another nation creates vigor, increase, and conservation, in ours, the opposite effect is produced: that is, the more powerful a state is, the more people it has that, out of their number, a sufficient number can be liberally distributed to cultivate the land, which is one of the principle sources of the country’s wealth; a sufficient number to serve in the militia, the embodiment of the sovereign’s power; in shipping, which through commerce, produces what is necessary and what is superfluous to all sectors of society, for the great number of poor people born daily forges the power of states, which employ these individuals in the various occupations dictated by public necessity. The Jewish Nation acts differently. Devoid of the privileges allowing it to engage in the mechanical trades, it cannot be employed in agriculture, shipping, nor in the militia, so that these four orders, so advantageous to another society, are not available to ours and the individuals that comprise it, are all reduced to the sad necessity of being a public charge, resulting in the great inconvenience of the few being under obligation to the many. This is contrary to the order of the entire world in civil society, where the majority maintains the minority and the contrary truly seems impossible. If, in this city of Amsterdam, the populace were not employed in the mechanical trades, in factories, in shipping, would it be possible to maintain good order? Would all of people’s wealth be sufficient to maintain the unfortunate? Surely not. And what would happen if the door were opened to the hapless Protestants of the entire world, scattered throughout Europe, Africa, and Asia? Even though it seems pious, would not the reason seem ridiculous, ruinous, and even impossible? For this is precisely what we did and are doing. We have opened the door to all the hapless Jews who come from Spain (which is just); we have opened it to those from Italy, France, England, the Orient, Poland, Barbary Coast, and finally, to those from Asia, Africa, and America. And, thus, imperceptibly, in four days, we find four hundred Jews, laden with close to eight hundred families, living or dying, at our expense. Evidence, based on the observance of a century, shows that the latter has increased more than the former, for, in the course of these last twenty-five years, the number of Jews and congregants has diminished from six hundred twenty-nine to six hundred ten, and the families receiving charity have increased from four hundred fifty to more than seven hundred fifty. [ . . . ]

May the difference of this progression be observed, and may consideration be given to whether it is possible to maintain this apparatus with the small number of Jews.

And what will happen here in another twenty-five years if poverty increases (I don’t say double, as previously stated) but by only one-quarter—which is bound to occur? What dire consequences would not befall us, making the ensuing disorder something to be feared? For necessity, poverty, misery, the desperation of not being able to find sustenance, lead the [Jewish] nation to turn to charity, thus giving rise to the same wretched and ignominious scenes which occur, for the same reason, among the Germans. The prisons will be as filled with Portuguese as theirs are with Germans; the gallows will familiarize themselves with their bodies and the most honorable will die destitute. The Nation will lose the luster with which it has glittered till now and will fall into the same disrepute in which it is held in some parts of the world.

Translated by

.

Notes

[Meaning of the original word, navegaçaó, uncertain.—Trans.]

Credits

Isaac de Pinto, Reflexoens Polίticas tocante a Constitução da Nação Judaica (Political reflections regarding the constitution of the Jewish nation) (Amsterdam: 1748), pp. 5–7.

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 5.