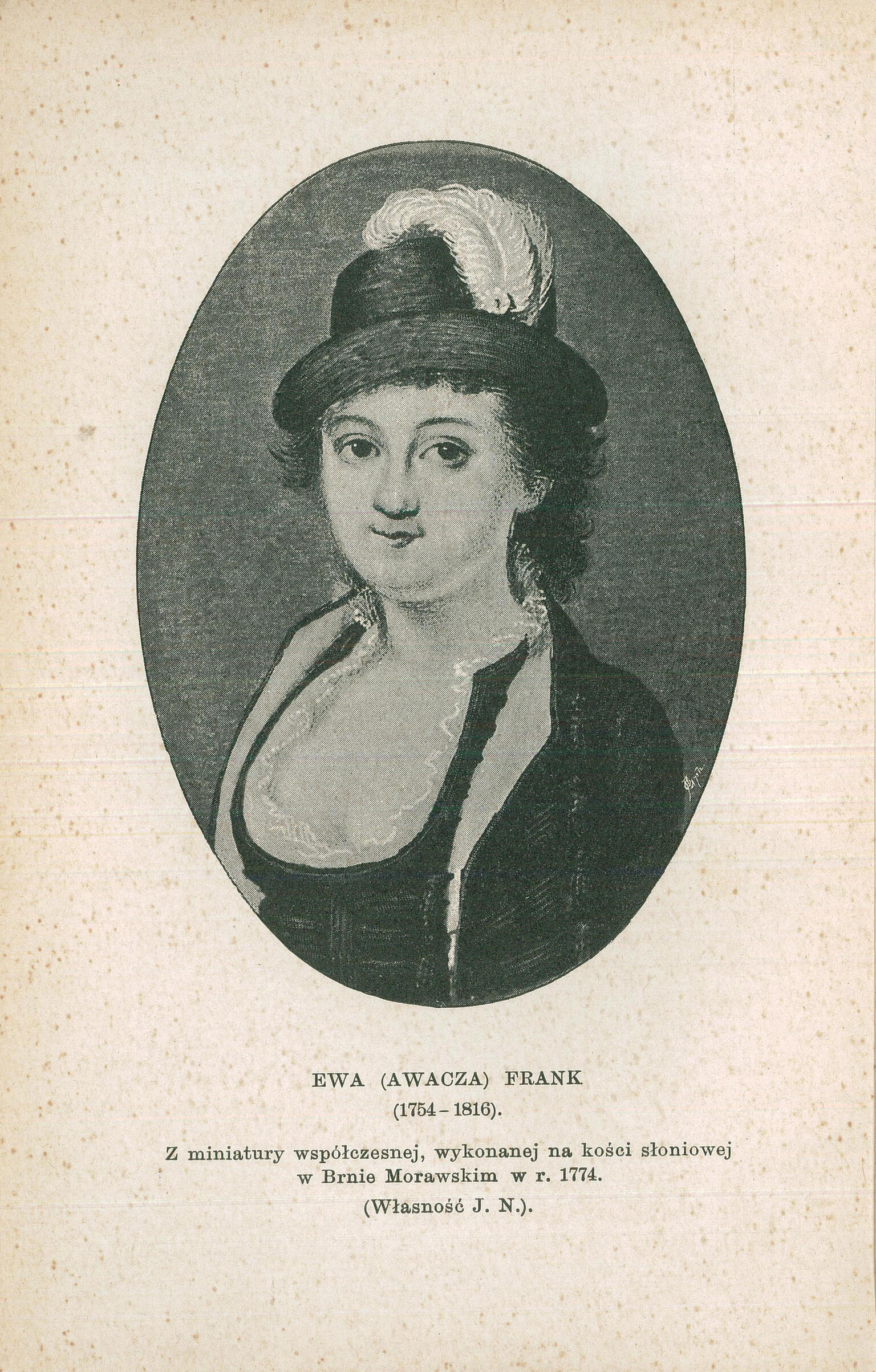

Portrait of Eva Frank

Aleksander Kraushar

ca. 1771

Eva Frank (1754–1816 or 1817) is one of many early modern Jewish women who overcame gender restrictions to take on influential roles as spiritual guides and teachers, even while society lagged along behind them. Born Rachel Frank, she was the daughter of Jacob (Jakob) Frank (ca. 1726–1791), a controversial and charismatic messianic figure who attracted a significant Jewish following in Eastern Europe. After his death, Eva took over as leader of the Frankists. She changed her name to Eva (Ewa) when the Frank family converted to Catholicism in 1760.

What challenges might Eva have faced as a woman in a position of religious leadership in this period?

How might the fact that Eva was the child of an established community leader have influenced her ability to challenge gender norms?

Is there a greater likelihood that a messianic movement that rejected many norms of traditional Judaism might create new opportunities for women?

Related Guide

European Rabbinic Scholarship

Despite the challenges of the early modern period, rabbinic scholarship flourished in Central and Eastern Europe in the latter half of the eighteenth century and the first half of the nineteenth century.

Creator Bio

Aleksander Kraushar

Born in Warsaw, Aleksander Kraushar was brought up in an affluent family, received a modern Polish-European education, and became a leading advocate for complete Jewish assimilation into Polish culture and nationhood. Studying law when the 1863 uprising against Russian rule in Poland broke out, Kraushar helped edit Prawda and Niepodległość, the rebellion’s journals. After the collapse of the insurrection, Kraushar completed his law degree, established a successful career practicing law in Warsaw, and married into the Polonized Jewish elite. An advocate of complete Jewish integration and assimilation into Polish society and culture, he contributed articles to the Polish-language Jewish integrationist journals Jutrzenka and Izraelita and hosted a salon that became a gathering place for Polish national cultural figures in Warsaw. Kraushar published historical works on Polish Jewish themes, legal scholarship, and poetry. In 1903, he converted to Catholicism.

You may also like

Gender Roles

Engage with the gendered dimensions of Jewish life and discover lost voices of Jewish women.