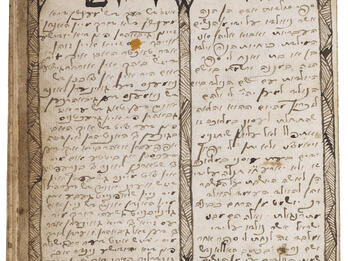

Letters

Diary, April 1799

I often said to a younger girl friend: “If you are marrying without love, after all, do not talk to your husband. Please him as much as your nature can tolerate; do not argue with him; never prove that you are right and that he is wrong. Look at F., she owes the tranquility of her life and her freedom to her silence. —I will explain it to you. One can do pretty much anything one pleases as long as one leaves the law intact—, but one must never insist on one’s point of view. Immediately they go on the attack and start proving; one is driven to defend oneself, the less one agrees with them. This is sufficient to disturb what you love most. Learn from the stupid and wicked how they achieve their advantage! What is their advantage? You may prove to them whatever you want; they may concede to you whatever they want, but afterwards they will behave just as they did before; and it is for naught that they appeared to change; it wasn’t true when you believed it. They just couldn’t offer you any good reasons for their behavior or lacked the courage to reveal to you its wicked causes, or they were unaware of them. You are hoping in vain; they are indestructible in their wickedness. In this you must become like them: they do not talk, they simply do as they wish; one never succeeds with them by talking to them; and that is how you should act too—; so much about love, do what you can manage—and for the love of yourself, remain silent.”

[Section in French:] What fate is comparable to that of man! His imagination deceives him and leads him astray; it depicts evils for him and pleasures that never come true. He who writes the history of a man only as a sequence of events does not teach us whether he was happy or unhappy. Beyond our feelings, it is the development of our ideas and thinking that determines our destiny. If one leaves to life only true happiness and the misfortunes that befall us, one will almost always curtail our sweetest pleasures and your most intolerable sorrows.

[She continues in German:] Time and again I made sacrifices for him, he did not turn to me; even among human beings one chooses for oneself a god; and they withdraw from us like gods.

Diary, Autumn 1799

What would that be like to become unhappy in one’s happiness? Would that be the most terrible of occurrences? There are even more painful sorrows; those I do not even know.

Diary, January 1800

This breast will never be completely healed, because it yearns for new duties. Victory!—Pooh! Being victorious. What does one gain by it? One’s own misfortune; and one must—one has to work for a world that one doesn’t know and that demands everything, everything one loves irresistibly for itself.

From a letter to Brinckmann, March 16, 1800

Whom am I expecting now? Dull Friend! Whom! “My significant person.” He is a Roman, twenty-two years old, commander of a brigade, wounds on neck and leg, and beautiful like a god. He is not coming here for the first time. He is proud, but that does not help him in the least. After all—isn’t he already coming to see me? Didn’t he lead me during the entire opera ball? Won’t he—if circumstances aren’t entirely unfavorable—have to do what I want him to do? Am I creating sorrows for myself? Yes. But I no longer shrink from them. How beautiful he is! You know him. Everyone fights at the beginning, and then—Pauline thinks he is divine.1 Her charitable instinct always made her say in the Tuileries, when I did not know him yet: “Just like a bear, don’t you think, Levin, just like a bear.” She had an inkling of the divine race and called it bear. To my brother I wrote recently: “I am also in love, but in a pleasant way.” I did not yet know him back then; now it’s no longer pleasant. Because, when he entered the ballroom, where I had already been for two hours for the concert, or, rather, when I became aware of his presence, since I had not seen him come in, I did not believe it; I examined it once more, and when it was truly he, I felt all my blood hard inside my chest; and then my heart surely beat for an hour in such a way that I can say I was passing through an illness. Then I fell into a drowsiness2 that was very much like ill-humor; for three half hours I sat on a chair; would have loved, right then and there, to tear off my bonnet, pearls, dress, everything and hide in the deepest depth of bed: God, how hideous I appeared to myself,—I have not yet been able to recover from that feeling,—and I would indeed have gone home, if it had been possible to suggest that to my companion. He saw me too, when I saw him, and the most flattering element of our acquaintance is for now the look, which conveyed his astonishment to see me. After that he was very proud. I wasn’t, but yet—. It was more than pride. Serendipity and his lady conducted him eventually onto an armchair so close in front of me that I had to remain seated; he looked at me only a few times and seemed to want to annoy me; I did not pay the least attention and looked about as I pleased; that was a better sort of pride, and more Roman than his; he began to take the fan away from his lady and to court her out of all proportion, because she appeared not to understand any of it; moreover she didn’t fit at all into his usual rhythm3 of moving. So I took that as a point in my favor and smiled for real; but that did not lighten my heart, which is still heavy. Suddenly the lady got up, said it was too crowded and left against his will, which he expressed gallantly in words and by walking with considerable hesitation. But he did not look at me and left. He was gone:—and I had stayed, deader than my chair, for an hour and a half. Finally I became furious, went looking for my escort in another room, wanted to go straight home and not to another carnival ball,4 but find my significant person in the company of my escort, who had been talking to him the entire time, almost alone—except for a game table, at which the lady was seated—and in excellent agreement. They exchange their addresses. Visits are planned and I am being introduced. Gregori is his name. Now it begins. Immensely respectful, eternally lovely, but proud; but I haven’t spoken with him alone. Do I please you? I am writing all of this because we are not together; and since you do not have me even piecemeal, I am letting you have a good chunk at one time. I am presenting myself black on white as a spectacle. And how right. But I have sense of foreboding: because I will have to bear the brunt of it and that never ends well,—or rather, that ends in nothing good,—because in such matters every ending must always be bad, and when they don’t end, that is the right end,—so “with courage, captain.” The5

Notes

[Pauline Wiesel (1778–1848).—Trans.]

[RV uses the French word assoupissement.— Trans.]

[RV uses Mensur, a form of fencing that is performed within a measured area (Latin mensura: measure).—Trans.]

[RV uses Maskenball—a masked ball.—Trans.]

[The hanging “The” is explained at the beginning of the next letter: RV breaks off when the Roman enters the room.—Trans.]

Credits

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 6.