Introduction: Ladino Translation of the Bible

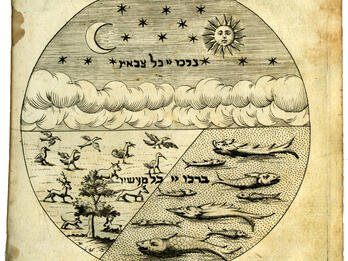

The Master of the Universe gave us the holy and blessed law so that we would enjoy l’olam haba [the world to come], so that we would know and see the light of eternal life. Study and a good understanding of it [the law] make it clear that everything is given by his blessed hand. One sees all the miracles God performed, and [that] he created the world by his word, as the pasuk [verse] says, bidvar h’shamayim nasu [by the word of Lord the Heavens were made],1 as you will see at the beginning of the Book of Genesis. And [you will see] the miracles he performed in Egypt in order to deliver us from the oppression of the great sorcerer, the Pharaoh. And all seventy umot [nations] agree about this holy law, there is not a single uma that would speak against this law. And in the whole law davka [only] the name of Israel is mentioned, and no other uma, even though the aralim [uncircumcised] say that God abandoned us and took them instead, saying that we had sinned. But we can easily respond to them: they could say such things if God had achieved something by taking better people instead of us. But this is not so, as we see that those who say that God abandoned us and took them instead are much worse sinners who do not perform a single mitzvah [commandment] of the law, ubifrat mitzvot milah [in particular, the commandment of circumcision], or hokim and gezaroot [rules and injunctions] of the law which God assigned them to perform. So, why would God who knows atidot [futures] abandon [us] without achieving anything? And they themselves, knowing that this is not so but [that] they found themselves in gdula [power] beavonotenu [for our sins], for siba [because of] our sins, are wondering why the Master of the Universe left them in galut [exile] for so much zman [time], despite their having such a holy law; and thus, based on their sbara [assumption], they say that he abandoned us; but kepi [according to] us, they do not have hakhrachah [need] for any tricks because they do not2 . . . the law was given to the zera [seed] of Abraham, Isaac, and Israel. . . . because their . . . did not want to accept the law . . .3 a different law which they have . . . and we received the holy law [the rest of the page is missing]

. . . And reading in Ladino afilu [even] an am haaretz [ignoramus] understands well and correctly performs what he reads. And the women who, like men, are obliged [to perform] rov [majority] of the mitzvot, are also obliged to study the law of God. And what the Gemara says, kol hamelamed et bato Torah keilu melamda tiflut [anyone who teaches his daughter Torah, it is as if he were teaching her rubbish], [relates] davka to the depth of the Halakhah [law] or secrets of the law. There is no reason for women to study whole dinim [rulings], but they are obliged to study the havanah [meaning] of how to perform the mitzvot, because if they do not know dinim how will they observe the Shabbat and the rest of the mitzvot? How will women learn to perform the mitzvah if they do not read about it? How will they learn that there is such a mitzvah in the law? For this reason, they are hayevot [required] to study in order to learn to perform [the commandments]. And we find that in the time of Hezekiah melekh Yehuda [king of Judah] the women knew ofi dinei teharot ve kdoshim [the nature of the laws of purity and holiness] which many men do not know now, and thus Sefer Hasidim4 contains a siman [sign] of God. And if they read and do not understand what can they learn? This Ladino [translation] is useful because both men and women will read and understand it, and they will fear God. And if they have sinned they will repent, and will be baal teshuvah [penitent], and will enter the Garden of Eden. And those who have not sinned at all, by reading and understanding, will never sin and will reach a higher madraga [level]. Another and greater advantage is that the din requires that one read shnaim mikra uechad Targum5 [the Torah portion twice and Targum once] every week. The Halakhah requires Targum davka. But Sefer ha-Agor, approved by the rabbis,6 says that, instead of the Targum, it is better to read the Ladino7 [translation] because the Targum is read in order to make the parasha [Torah portion] comprehensible, but now that we do not understand the Targum, it is necessary to read it in Ladino so that one would understand what it says; this is what Sefer ha-Agor, approved by the rabbis, says. It states that every week men are required to read the parasha twice in lashon ha-kodesh [the holy language] and once in Ladino davka. Thus one performs the din and the obligation to read the law. And if he prefers, he can also read the Targum in order to fulfill yadei huva [obligation] of the Halakha, but in order to understand what he reads it is certainly better [to read in Ladino?] . . . This is what I advise in the haqdamah to the tefila [prayer] book in Ladino which I have just [printed?] . . . lashon that one understands, as is recommended by many books, you will see . . . every Sabbath one can choose . . .

Notes

Words in brackets appear in the original translation.

Ps 33:6.

[The sentence seems to suggest that nothing would help them (Christians).—Ed.]

The author seems to suggest that their ancestors accepted the wrong law.

Sefer Hasidim (Book of the Pious) by Judah ben Samuel of Regensburg (1140–1217) consists of “signs,” i.e., sections, one of which deals with women’s education.

The Aramaic translation of the Bible produced for the benefit of Aramaic-speaking Jews who did not know Hebrew.

Sefer ha-Agor (or [also known as The Agur] by Jacob ben Judah Landau (d. 1493) was an authoritative law code composed for the education of the rabbi’s student who was a layman. The Agur was the first Jewish work containing a rabbinical approbation. It received approbations from many famous rabbis, including Judah Messer Leon. (s.v. “Approbation” in the Jewish Encyclopedia.)

Landau obviously meant any vernacular translation.

Credits

Abraham Asá, from “Publisher’s Introduction” to the first Ladino edition of the Pentateuch, trans. Olga Borovaya (Stanford, Calif.: Sephardic Studies Project, Taube Center for Jewish Studies Stanford University, 2014; Ladino.Stanford.edu). Used with permission of the translator.

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 5.