The History of Borsszem Janko (Johnny Peppercorn)

I was lying in bed sick when, on January 5th, 1868, the first issue came out. Understandably, the party line and the competition tried to alienate from me János Jankó, the illustrator of the opposition’s two papers, Bolond Miska [Crazy Michael] and Üstökös [Meteor]. Moreover, he himself was a hardcore leftist. But no matter how loyal he was, he promised to help me until I found someone to replace him. I just had to do this quickly.

We were in labor with the first issue for a long time before it was born. I could hardly boast about its success. Only its tone was unusual; the jokes poking fun at the opposition—these gentle attempts—shocked that great minority beginning with Kálmán [Tóth] and all the way down to Pista Mónár,1 behind whom stood “the majority of the country.” The poems to accompany the small images were written by Gereben Vas; Hugo Maszák wrote articles about the Pest police; Pál Gyulay gave a few gentle strokes to the noble magistrate;2 Lajos Hevesi sang about the quotas; Aurél Kecskeméthy neutralized [Lajos] Csernátony; and my job was to expose the rest of the trifles and the travesty of the subscription program.

Up until the eleventh issue, the first page featured the artistic but humorless full-page vignette of the Viennese [artist Franz] Kollarz. There Borsszem Jankó [Johnny Peppercorn] is still a sour-faced, ugly, and skinny lad with the withering features of a changeling. He sits on a wooden horse that whistles from the back, and is surrounded by little chubby figures—who accompany him on his first trip to the unknown—flying around him. Miklós Barabás’s sketch portrayed him as more of a Hungarian type, but the skillfulness of the other version enticed my eyes and my heart, and I settled on the Viennese drawing. But I decided for myself that I would either expel this downcast figure from the first page of my paper, or would covertly make him younger and round him out, and I would explain this by including more refined intellectual content; because, in fact, Borsszem Jankó was getting stronger from one issue to the next, and as he progressed in age, he became younger.

Every week I had to travel to Vienna where the since-deceased Vincze Katzler drew the sketches and the Waldheim Institute prepared the engraving. Meanwhile, Mihály Szemlér helped me out once. [Zsigismund] Pollák, our wood engraver, was overloaded with work, and Rusz, the engraver of Bolond Miska, didn’t want to support Borsszem Jankó. “It won’t live to see the new quarter.” [ . . . ]

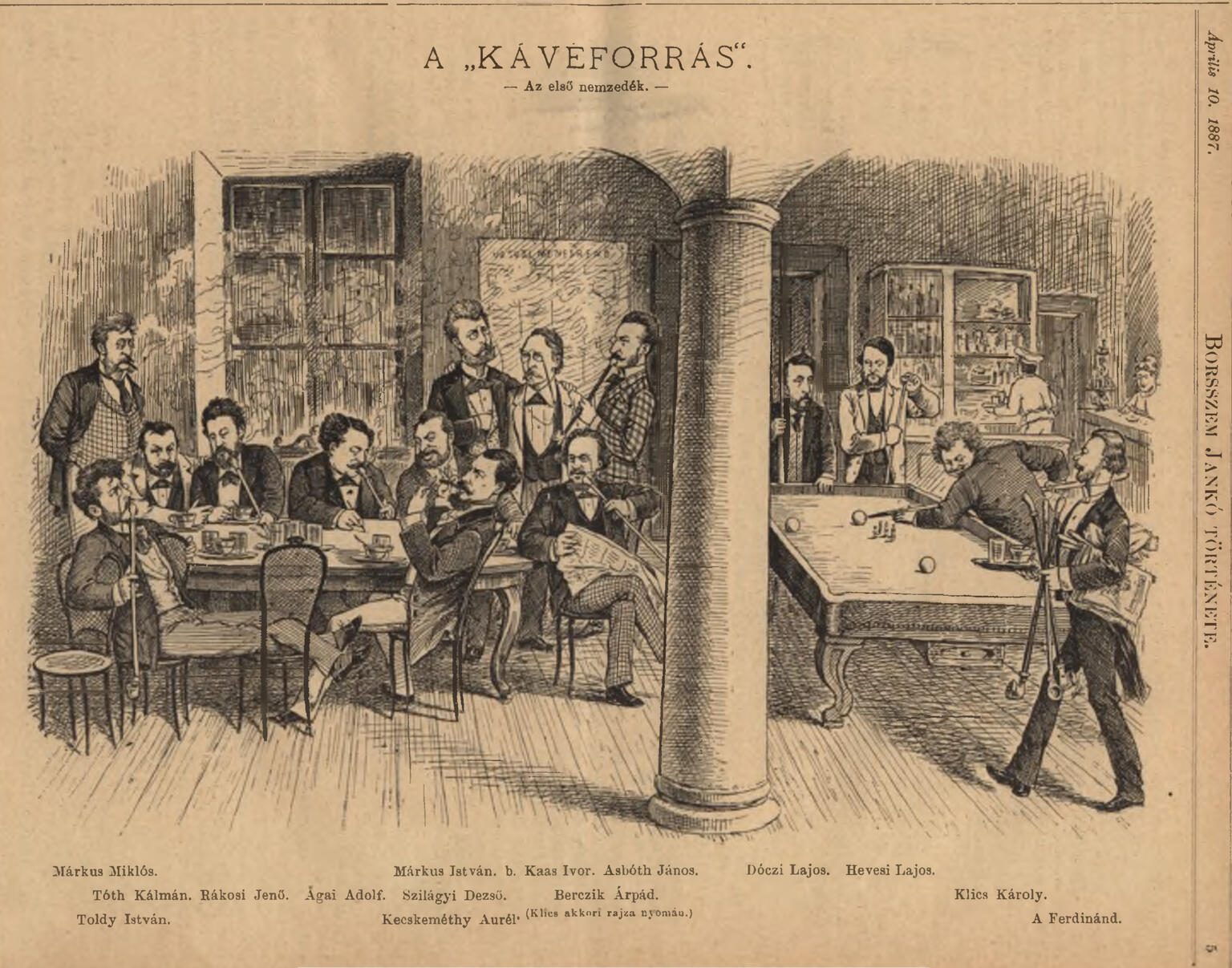

The Coffee Fountain

First Generation

The driving force behind the impact of this paper and the source of its success is the “Kávéforrás.”

A bunch of young writers set up shop in one of the houses on Fürdő Street in an environment free of conservative classicist intellectuals, far from literary and artistic circles—a neutral atmosphere free of muses, among hard-working timber merchants. Today, if we peep into that building through the thick windows, we will see gold embroidered velvet furniture and curtains, Japanese vases, and other luxurious objects.

Even though the room they occupied was dim and dark at the time, it sparkled with their witticisms; the thick smoke of pipes couldn’t conceal their dazzling wisecracks. All I had to do was gather them in a bunch and with them, entertain the educated public of a great country from week to week. And the rest of the wisecracks, the ones we just said for our own pleasure, would have made for some fireworks, too.

One morning we woke up to the fact that this coffeehouse had become Borsszem Jankó’s workshop—where its text was written and its illustrations were drawn.

Written in Budapest on April 4, 1887.

Csicseri Bors.

Notes

[Kálmán Tóth (1831–1881), a poet, playwright, and journalist. It is unclear to whom Mónár is referring.—Eds.]

[Presumably Emperor Franz Joseph I (1848–1916), though possibly Gyúla Andrassy (1823–1890), the Hungarian prime minister who signed the 1867 Austro-Hungarian Compromise.—Eds.]

Credits

Adolf A?gai, “A ‘Borsszem Janko?’ to?rte?nete” [The History of Borsszem Janko? (Johnny Peppercorn)], Borsszem Janko?, Apr. 10, 1887, pp. 1–12.

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 7.