Ginat veradim (Rose Garden)

Section 5

There was an incident involving a woman who came before the court to get a divorce. Her name was Melok, and she had no other known name at all. It occurred to me in this regard that the name Malkah is sometimes changed to Melok, in the manner of a nickname, and thus the name Melok would be a shortened form of Malkah, just as Yitzḥak is abbreviated to Ḥakun. However, we cross-examined this woman and she maintained that she has no other name at all. If so, this Melok is an Arabic name, like the name Najim, meaning stars, which expresses the idea that the woman is as important as the stars. The name Melok, which means kings [melakhim] can be interpreted in a similar manner, that this woman is as important as kings. If this explanation is correct, then there is no other way of writing the name at all. For if it were a form of the name Malkah, one could remedy the matter by writing down the main name, but in this particular instance there is no other name whatsoever.

A dispute also arose regarding how this name should be written. Some said that it should be written as Melokh, without a diacritic dot in the kaf sofit, but I disagreed with them, as I maintained that a diacritic dot is required in the kaf sofit, in order to facilitate the proper reading of the name and its correct pronunciation. The argument of those who said that no dot should be written is that a bill of divorce is called a sefer [“scroll”; Deuteronomy 24:1], and that just as diacritic dots are not inscribed in scrolls, so too they should not be written in bills of divorce. I did find for them a source that supports their view. [ . . . ]

In sum, to fulfill our obligation according to R. Joseph Trani, who is stringent, and to do that which is good and upright in the eyes of the other authorities, it is proper to write it with a diacritic dot. However, when I saw that those who disagreed with me persisted in their opinion, I felt that it was better to avoid strife and to write two bills of divorce. [ . . . ] Nevertheless, they would not let the matter go, for they claimed that writing a bill of divorce with a diacritic dot would lead to a general misunderstanding, for when things quietened down people might say that this dot was like a vowel, and yet one may not insert vowels into a bill of divorce, as “a scroll that contains vowels is invalidated” [Shulḥan ‘arukh, Yoreh de‘ah 274.7]. [ . . . ] Ultimately, in order to placate me they concluded that the bill of divorce should be written without any diacritic dot, and it should be given to the woman in accordance with all its laws and requirements, but subsequently, after the woman had received it from the husband it should be taken back from her, and a diacritic dot should be inserted into the kaf. Then the husband should give it to her once again, and as soon as the woman had received the bill of divorce for the second time it should be taken away and thrown into the fire. Thus, this bill of divorce with a diacritic dot that had been given under the auspices of the court would never be seen or found, and this will remove a potential stumbling block from future generations.

When I understood the situation, I decided that this was not a time to remain silent and I felt compelled to write concerning R. Samuel de Medina and declare that his opinion is of no substance, and may his Master forgive him, Amen. For this claim of R. Samuel de Medina, that one should be stringent and not write a rafa mark [which indicates the “J” sound] because a bill of divorce is called a sefer, is incorrect. For the fact that it is called a sefer only serves to teach us that it must contain an account [sipur] of the matter [see b. Gittin 21b]. [ . . . ]

We can now conclude that all the stringencies practiced with regard to bills of divorce are not on account of the fact that it is called a sefer; rather, they are designed to ensure that it will be read perfectly correctly, without any doubt or uncertainty. Accordingly, we can infer that it is better to insert vowels into some words in a bill of divorce, so that it will be pronounced in the proper manner. It should not be left without vowels if this will give rise to uncertainty in the mind of the readers; the sages were displeased with such a practice. Nevertheless, some authorities ruled that if the name Jamila was written without the rafa mark, the bill of divorce is valid. It seems that the reason is that if it is read by intelligent people, then even if there is no rafa mark on the letter gimel they would know for certain that this is the name of the woman, and that she is called Jamila. This is because they too, when they write their own documents and correspondence, often in their haste omit these rafa marks, and they are not particular about them unless they are writing slowly and carefully.

It can be inferred from the above that we should be stringent in the case at hand. For scribes are only careless and leave out the rafa mark in words such as Jamila and Joya, whereas when it comes to a word that ends with a kaf sofit, and which is read with a diacritic dot, they are invariably particular to inscribe the dot inside the letter, and they join the edge of the kaf sofit to the dot. They do not wait to add the dot only after the completion of the whole line, which is what they do for words that require a rafa mark above them. If a scribe makes a mistake and neglects to put the dot in the kaf sofit, when he reviews the text to examine whether or not it contains errors and he realizes that he neglected to include this dot, he would write it at that stage, which is something he would not do for the marks on the tops of the letters.

The reason for this difference is that since the letter gimel and the regular forms of the letters kaf and peh frequently appear both with and without a diacritic dot, someone who finds a gimel or kaf or peh without a rafa mark would not necessarily read it as though it had a diacritic dot. Rather, they would consider the meaning of the whole word, and thus they would read the letter correctly, as though it had a rafa mark on it. By contrast, a kaf sofit, which comes at the end of the word, appears only in the soft, rafa form. Thus, even if it has no rafa mark, it would still be read in that manner. For it is only in foreign words that a khaf sofit at the end of a word has a diacritic dot and is pronounced as a resting sheva vowel. Conversely, if it does not have a sheva, but rather the kaf is articulated, for example vi-ḥuneka (and be gracious to you; Numbers 6:25); asher ar’eka (which I will show you; Genesis 12:1); ‘al panekha before you; Exodus 33:19); yevarekhekha (may He bless you; Numbers 6:24), then it can sometimes have a diacritic dot. This is because such words ought to have a regular kaf followed by the letter hey, as in ve-lo ya’anukhah (but they will not answer you; Jeremiah 7:27), and va-ḥasidekha yevarkhukhah (and Your pious ones shall bless You; Psalms 145:10), but in order to make it easier for scribes, the hey is omitted and a kaf sofit is used instead. However, when the kaf is read with a resting sheva vowel it should not be followed by any other letter at all, and in that case it appears in the soft form. It follows that when the reader finds a word that ends with a kaf sofit and a resting sheva vowel, it will not occur to him that this specific word should be read with a diacritic dot; rather, he will naturally read it in the soft form. And since when it is read in this manner it is not clear that it is the name of a woman, this entails a major problem, so much so that it is possible that the bill of divorce is invalid even according to the lenient opinion regarding the gimel of Jamila. [ . . . ]

Incidentally, I have found wealth for me (Hosea 12:9) as a result of the claim of certain rabbis regarding why I am particular and “scream like a crane” [see, e.g., b. Kiddushin 44a] in a situation where a foreign name must be written down, such as Signora and the like, as I maintain that it must be written with the letter samekh rather than a shin. My colleagues objected to this practice of mine, arguing that in the foreign language the proper way to write the name is with a shin, as they do not have a samekh in their alphabet at all. I responded to them with a proof from their own practice, as they write the names Graciosa, Leticia, and many others with a samekh, not a shin, and they can’t have it both ways.

However, the fundamental point is that the speakers of the foreign language are unable to articulate a shin properly—they invariably pronounce it as a samekh. Likewise, the Greek letters, in which these foreign speakers write their language, do not include a shin at all, as they too do not distinguish the inflection of a shin from that of a samekh and they are unable to pronounce it correctly. Consequently, these foreign speakers, who are a stammering people [see Isaiah 33:19], write their books and communiqués with the letter samekh, even when they use the Hebrew alphabet. By contrast, we who live in these regions, who articulate clearly and for whom there is a great difference between the sound of a samekh and a shin, when we pronounce the name Signora we actually do so with the letter samekh, and if we were to use a shin we would be laughed at. It is therefore appropriate for us when writing this name to use a samekh, so that its written form should match the way it is pronounced. This is indeed our practice in written communications, to write it with a samekh. If so, why should a bill of divorce be any worse, that we should write it in the language of a stammering people, when that is not its best form? It should be noted that the above applies specifically to the letters samekh and shin, whereas with regard to the letters kaf and kof we too are like the foreign speakers [ . . . ]

Another issue I wish to discuss in passing is a comment of R. Jacob Castro, section 129, Law 17: “If the father of the husband or the father of the wife has a title of their own, it should not be written in the bill of divorce at all.” [ . . . ] The rabbi did not explain the reason for this, but it appears to be in order to avoid the erroneous impression that this title for the father is actually referring to the son, the one who is divorcing. For we find that the sources are not particular in this regard, as they will sometimes record the son’s title after mentioning the name of his father. For example, “Saul, son of Kish, king of Israel” [b. Yoma 22b], when technically it should state “Saul, king of Israel, son of Kish.” Similarly, and they took Lot, and his goods, Abram’s brother’s son (Genesis 14:12), when it should have said “and they took Lot, Abram’s brother’s son, and his goods.” It can thus be inferred from here that even when the title is mentioned at the end, after the name of the father, it is possible for someone mistakenly to think that it is referring back to the man who is divorcing. This can have dire consequences, as people might claim that this is not the man undergoing the divorce, as he did not have that title. Therefore, the father’s title should be left out. This omission is not a problem in and of itself, even if he was known by that title, as it is included by the standard clause: “and any other name that I or my father have.” It seems to me that this requirement is necessary only ab initio, but the bill of divorce is valid after the fact.

Credits

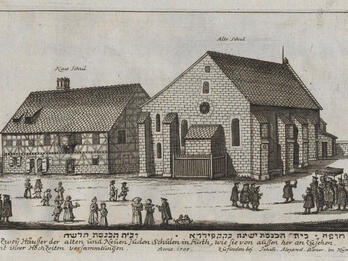

Abraham ben Mordechai ha-Levi, Ginat veradim (Rose Garden), vol. 2 (Constantinople, 1716), section 5.

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 5.