The Essence of Baseball Explained for Non-Sportsmen

Uptown, at 9th Avenue and 155th St., stands the famous field—the Polo Grounds. Every afternoon, 20,000–35,000 people gather there. The entrance fee is from $0.50–1.50. Thousands of poor boys and older people save up money from their necessities to pay for a ticket. Baseball is played there by professionals, and the tens of thousands of spectators, who sit on rows and rows of seats all around the big field, get all worked up with enthusiasm. They shout, they jump up and down, they simply go crazy with rapture when one of “theirs” “delivers,” or with pain and despair when he is unsuccessful.

A similar scene also takes place in another location—in Washington Heights. Exactly the same scene takes place in Brooklyn, in Philadelphia, in Pittsburgh, in Boston, in Baltimore, in St. Louis, in Chicago—in every city in the United States. The newspapers print the results of these games and describe the actions. Tens of millions of people avidly grab the papers to read about [the games], discuss, and debate this and that aspect of them.

All this refers only to the professional games, but nearly every boy, nearly every young man, and not a few of the middle-aged, play baseball themselves—they belong to baseball clubs and are very excited about baseball. Every college, every school, every small town, almost every society and every workplace has its baseball team.

Millions [of dollars] are made from the professional games. That involves a special sort of political struggle among different cities. A good professional player earns between $8,000 and $10,000 for one season. Some of them are educated people who have graduated from college.

For us immigrants it all seems like a kind of madness. But in that case, it is worth understanding what kind of madness it is. If a whole nation is made crazy by a thing, it makes sense to know what this thing consists of.

We will therefore explain the game of baseball. But we won’t do it in the professional language in which the American newspapers talk about this sport. We must confess that we wouldn’t be able to speak that language even if we wanted to. We will therefore explain it in plain, very unprofessional, and very unscientific Yiddish.

What does the essence of the game consist of?

In the game two parties participate, each party consisting of nine people. (That kind of party is called a team.) One team takes the field and the second one plays the role of an enemy. The enemy tries to hinder the game of the first team and this first team tries to defend itself against them. We will therefore call them the “defensive team” and the “hostile team.”

So the defensive team takes the field and plays. Two of its nine members are actually playing and the other seven stand guard at seven different places. What this guard activity consists of we will see later, but first let us examine the two active players.

One of them throws the ball to the second one, who has to catch it. The first one is called the pitcher (thrower) and the second one the catcher.

The catcher throws the ball back to the pitcher every time. The reader may therefore ask: if that is the case, then each time the roles are reversed—the catcher becomes a pitcher and the pitcher becomes a catcher. So why is each of them called a specific name, one the pitcher and the other the catcher?

But we will soon see that the fact that the catcher throws the ball back is of no importance. The essence of the game is that every time the pitcher tries to throw the ball to the catcher, the opposing team tries to hinder him. The hindrance consists of the following:

One of its nine members stands, while holding a thick stick (bat), between the pitcher and the catcher (quite close to the catcher) and as the ball flies from the pitcher’s hand, he tries to push it back with the stick before the catcher catches it.

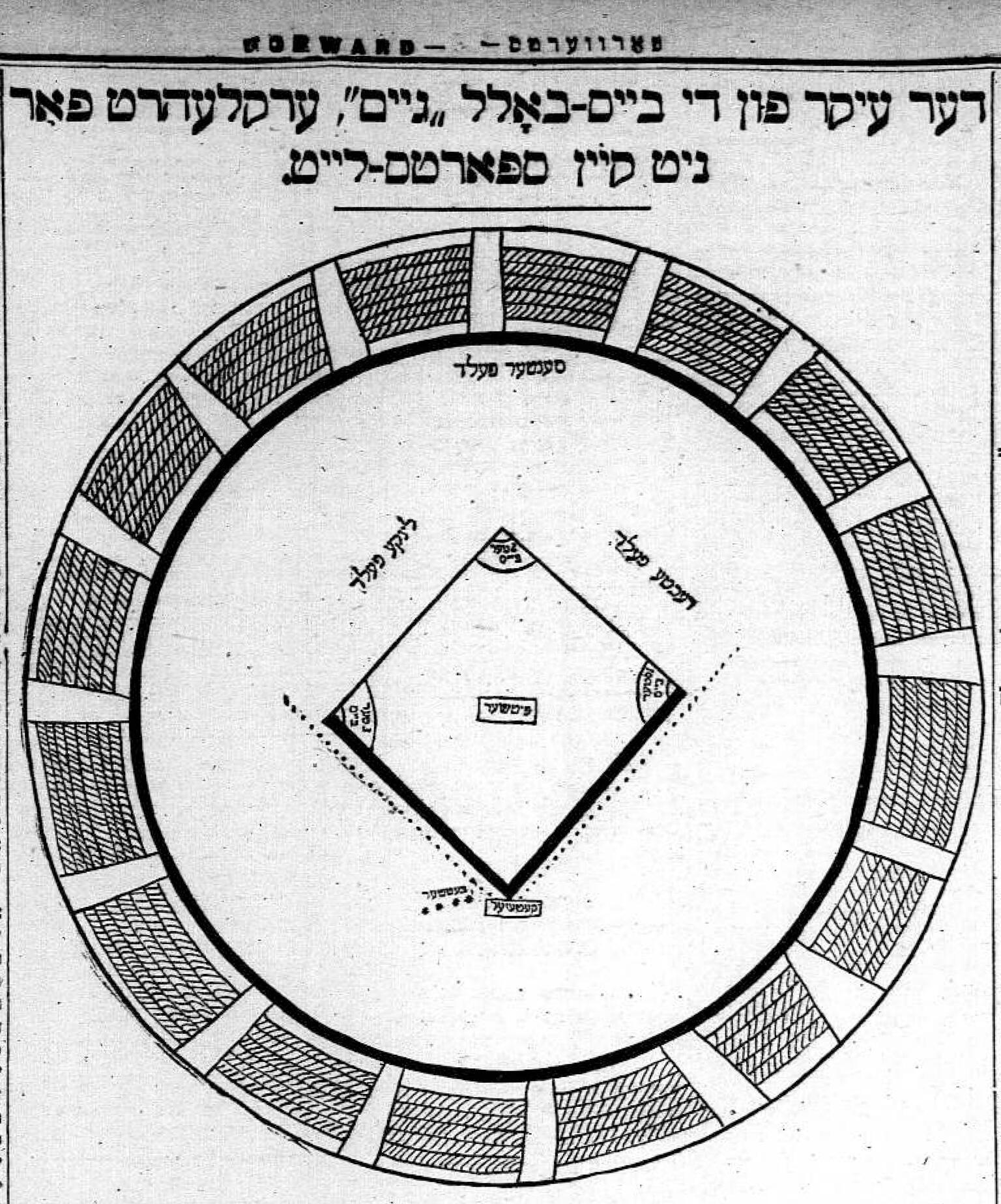

This opposing player is called the batter. The place where he stands is marked on our picture with several asterisks (****).

(The other eight players of the opposing team do not participate for the time being. Each of them is waiting for his next [turn].)

Now imagine that the batter, that is, the opposing player, hits the flying ball with his stick and sends it flying. If in doing so he does not violate certain rules, which we will speak about later, it now depends on what happens to the ball. If one of the watchmen catches the ball that has been hurled back while it is still in the air, then it means that this batter’s opposition is totally destroyed and the batter himself has to leave his place. He is excluded (He is out). He puts down the bat and another member of his team takes his place.

The role of the seven watchmen is therefore clear: they must try to catch the ball when it is hit back and thereby overcome the enemy’s hindrance and invalidate the hinderer himself. They stand at different places, since you cannot know in which direction the ball will fly when it is hit. They guard the different directions, so that wherever the ball may fly there should be a watchman ready to catch it.

The reader can see from our picture how the seven watchmen are distributed.

The whole official field, on which [the game] is played is four-sided and four-cornered.

On our picture, that is in the middle. (The two round lines that appear on our picture, with the dashes all around, represent the place with the tens of thousands of seats for the public. That is how it usually is for the big professional games. All in all, it seems like a huge circus with a roof only for the public. The field and all the players are under the open sky.)

As the reader can see from the picture, one corner is occupied by the catcher. The other three corners of the quadrangle are stops, each of which is called a base. As the catcher stands facing the pitcher, the first base is located on his right-hand side, right in front of his face is the second base, and on his left-hand side is the third base.

A sack of sand lies on every base. The watchmen, however, are not allowed to stand on the base, only next to the base.

So far we have only three watchmen. They are called first-baseman, second-baseman, and third-baseman. A fourth watchman stands between the 3rd and 2nd bases. He is called short stop. When a ball has been hit back, it often comes in this direction and the short stop has a chance to catch it in the middle of its flight.

In case the ball flies over the heads of these four watchmen, three more watchmen stand far outside the official field. They stand therefore on the outside field (outfield). One of these three watchmen is called rightfielder, the second centerfielder, and the third—leftfielder.

Two of the four sides of the quadrangle are marked with dots on our picture. If one of the balls is hit across one of these two sides, it is called a false ball (foul ball). To be a proper ball (a fair ball) it must fly straight ahead or over the other two lines of the quadrangle.

If the batter doesn’t hit the ball with his stick at all, it is called a strike. If he makes three strikes, he is out—excluded. Certain foul balls are also considered strikes, but we won’t go into the details here.

If the batter hits the ball back and the ball is a correct [fair] ball and the watchmen don’t catch it, it means that the opposition in this case is successful. But this success can be bigger or smaller. In order to measure the size of the success, the following is done: as soon as the batter hits the ball back, he throws down his bat and starts to run. If nothing hinders him, he runs to the 1st base, from the 1st to the 2nd, from the 2nd to the 3rd, and from the 3rd to the place where the catcher stands. This place is called home. If he comes home to this place, it means that the success of his opposition is complete.

That means he has made a whole [home] run and the outcome depends on these runs. Whichever team makes the most runs is the victor.

But making a whole run all at once doesn’t happen that often. The blow the batter gives the ball has to be unusually successful. More often, he may have time to make a quarter-run, or two quarters, or three quarters.

The rule is the following: the running batter has no right to occupy first base if the watchman there (the first baseman) at that moment has the ball in his hand. If the ball that has been hit falls on the ground and one of the watchmen picks it up, the batter is not yet excluded [out]. He runs, but imagine this: the watchman throws the ball to the first baseman and the first baseman catches the ball before the running batter reaches first base with his body. Then this runner really is excluded. But if he catches the ball when the runner is already on the base, then the runner is rescued (safe).

If the runner runs further, to second base, the rule is a little different. The 2nd baseman can invalidate him merely by touching him with the ball and the same rule applies to the 3rd baseman. They too have to touch him with the ball to exclude him [tag him out]. He can also be excluded [tagged out] with a touch by the catcher or the pitcher, if he happens to be near the base or the home to which [the runner] is trying to run up to.

The essence of this rule is that the runner can only occupy a position when the ball is not to be found there. So the presence of the ball has a kind of holiness. When the enemy runner runs to the bases or home, he trembles before the ball like a devil trembles before a mezuzah. The opposing runner has no dominion over it.

It sometimes happens that he is running all the way to home, but at that moment one of the watchmen throws the ball to the catcher and the catcher touches the runner a moment before he reaches home. Then he loses everything and is excluded [out].

He runs with all his might and while he is running he has to watch what is happening with the ball. If the ball is lying on the ground somewhere and he thinks he has enough time to run, he runs. He runs to 2nd base, for example, at the same time that one of the distant watchmen bends down to pick up the ball. Then he must decide whether he has time to run to 3rd base before that watchman throws the “mezuzah” to the 3rd baseman. If he believes he doesn’t [have time] he runs back as if he had been poisoned right back to 2nd base. But the “distant watchman” also grasps the situation and throws the ball not to the 3rd baseman, but to the 2nd baseman, so the runner will be invalidated with a touch when he runs there. He then runs back to 3rd base, but in the meantime the second baseman throws the ball to the 3rd baseman. So the runner runs back and forth trying to avoid the ball. He and the basemen watch each other like a cat and a mouse and the spectators go wild with pleasure and excitement.

Credits

Unknown, “Der iker fun di base-ball ‘geym,’ erklerhrt far nit keyn sports-layt” [The Essence of Baseball Explained for Non-Sportsmen], Forverts, Aug. 17, 1909, p. 2.

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 7.