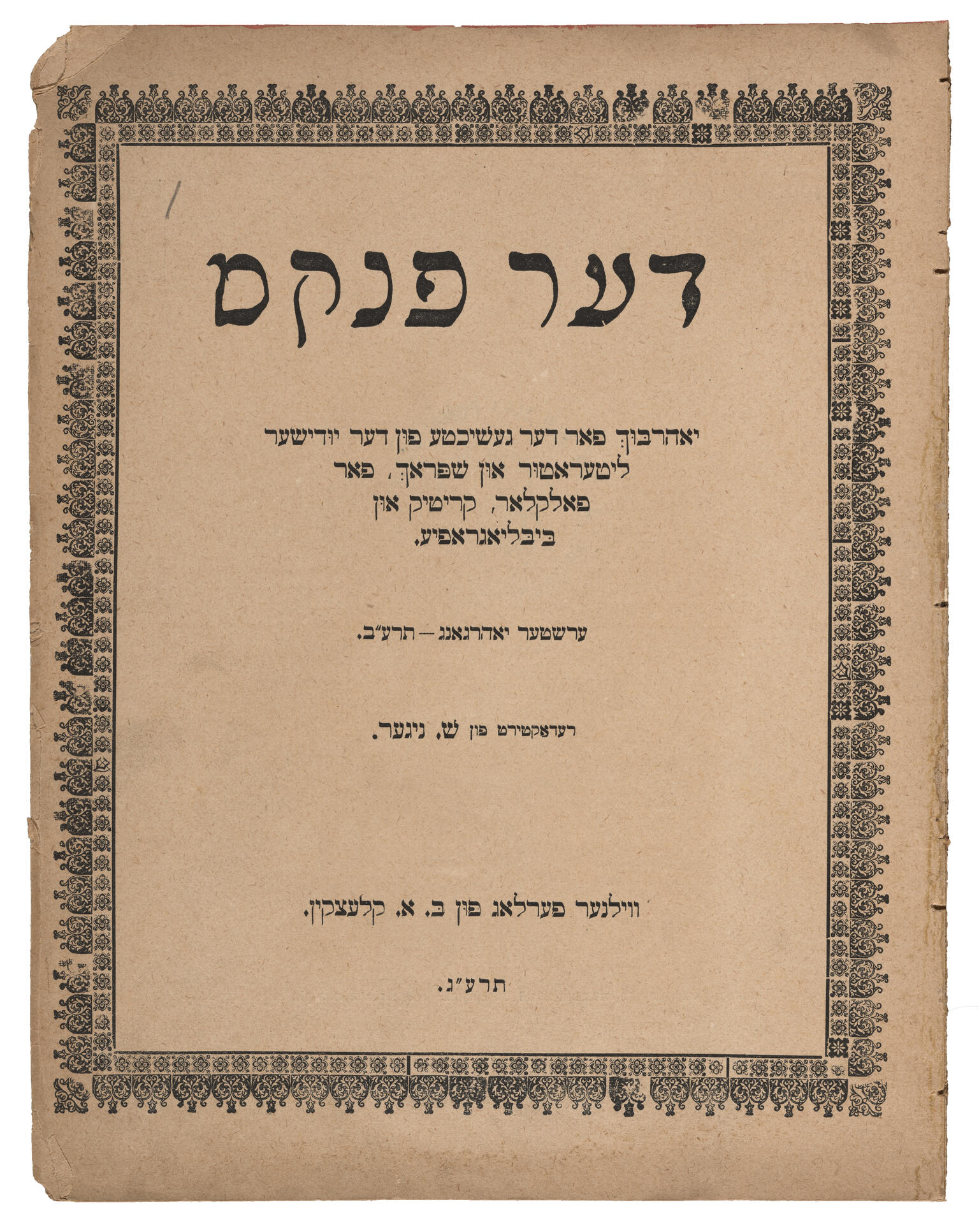

Der pinkes (cover)

Shmuel Niger

Ber Borochov

Zelig Kalmanovitch

1913

Creator Bio

Shmuel Niger

The Yiddish literary critic Shmuel Charney, who adopted the pen name Shmuel Niger as a young revolutionary and writer, grew up in fervently Hasidic surroundings in the Belorussian region of the Russian Empire. At the age of seventeen, in the middle of advanced religious studies, he abandoned religious observance. Becoming active in widening Jewish intelligentsia circles that advocated a mix of socialist and cultural nationalist ideas before and during the 1905 Revolution in Russia, he devoted himself thereafter intensely and exclusively to the cultivation of modern secular Yiddish literature and culture. By 1907 and 1908, he had begun to emerge as a leading champion of the fledgling Yiddishist movement and as the most influential Yiddish literary critic of the next decade. Fiercely committed to the idea that Yiddish should become the chief language of Jewish culture while Jews recast themselves as a secular diasporic nation, he also demanded that the Jewish intelligentsia approach Yiddish literature and culture as valuable ends in themselves rather than subordinating them to narrow party-political agendas or treating them merely as disposable tools of popular enlightenment, famously articulated in 1908 in the short-lived but influential journal Literarishe monatsshriften. Within the literary sphere, Niger emerged as a champion of the neo-Romantic aesthetics of the mature Y. L. Peretz and the young Sholem Asch, and more generally as an enthusiast of all forms of literary creativity that, in his view, had the potential to help bring about a “Jewish national renaissance.” In later years, Niger also wrote pioneering work in Yiddish cultural and literary history, including an influential essay on the role of women readers in the shaping of modern Yiddish literature. In 1919, disillusioned with the Russian Revolution and barely escaping death at the hands of the invading Polish army, he left Vilna for New York City, where he played a central role in the American Yiddish cultural scene as a literary and cultural critic. Among his more notable later works was a pioneering Yiddish biography of Y. L. Peretz and a book-length defense of the equal value of Hebrew and Yiddish as languages of modern Jewish creativity.

His exact intent in taking the pen name Niger, pronounced according to most sources like the American racist epithet, is unknown. It does seem that he meant to invoke associations with contemporary racism directed at African-Americans and people of African descent generally, and he may even have meant the racist epithet that the Yiddish pronunciation of his pen name elicits. Possibly he also meant to evoke the meaning of his real name, Tsharni/Charney, which is linked to the Slavic root for the color black. Most scholars find it hard to imagine that he identified with white racism, however. It seems much more likely that he chose the moniker out of a sense of his own targeted status as a revolutionary and/or Jew under the oppressive tsarist regime. In scholarly terms, Niger is the standard transliteration of the name under which readers will find all his Yiddish work. For this reason, the Posen Library retains the pen name as the author’s primary identifier.

Creator Bio

Ber Borochov

Born to a maskilic family in Zolotonosha, near Poltava, a southern frontier region of the Russian Empire (today in Ukraine), Ber Borochov (Borokhov) attended gymnasium and studied at the university in Ekaterinoslav, where he grew active in socialist and then Zionist-socialist politics. His greatest significance inheres in his efforts to replace the purely voluntarist, ethical, and utopian ideals of socialist Zionism with a properly “objective marxist” argument that unavoidable economic and political conditions in backwards and multiethnic Eastern Europe would inevitably provoke antisemitic exclusion or structural marginalization in the labor market and thus produce a vast unemployed Jewish Lumpenproletariat. Ironically, these objectivist arguments served as especially compelling subjective arguments for Russian Zionist youth of the 1905 generation, who were immersed in Marxist ideas and felt cornered by various non- or anti-Zionist socialist arguments in Jewish youth circles. With the older socialist Zionist Nachman (Naḥum) Syrkin, Borochov founded the Po’ale Tsiyon—the Jewish Socialist Democratic Workers Party; his 1906 “Nasha platforma” (1906) became the party’s manifesto, influencing among others the young David Ben-Gurion. Living in Vienna between 1907 and 1914, Borochov developed an ever greater interest in the Yiddish language, which he came to see as the chief language of the emerging transnational Jewish proletariat and as a national value in itself; his “Tasks of Yiddish Philology” was as influential in Yiddishist-diasporist circles as his Zionist writings had been in Russian and Yishuv Labor Zionist circles. Remaining an active organizer-leader of Po’ale Tsiyon, Borochov returned to Russia from New York during the first heady days of the Russian Revolution and died while on a speaking tour. His body was interred in Israel in 1963.

Creator Bio

Zelig Kalmanovitch

The Yiddish linguist and historian Zelig Kalmanovitch was born in Goldingen, Courland (now Kuldiga, Latvia). Before World War I, he showed a keen interest in the politics of diaspora nationalism as well as in Yiddish linguistics and literature. In 1919, he received his doctorate from St. Petersburg University, settling in Vilna in 1928 where he became a leader of the YIVO and the editor of its major journal, YIVO-bleter. Kalmanovitch was a major cultural leader of the Vilna ghetto, where he kept a diary in Hebrew in which he questioned the viability of armed resistance and supported Jacob Gens’s policy of buying time through productive labor. This diary was found by Avrom Sutzkever after the war. Deported to labor camps in Estonia in 1943, Kalmanovitch died in the fall of 1944.