A History of the Jews of Turkey and the Orient

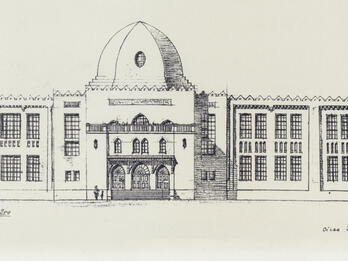

The Chief Rabbinate of Adrianople

Privileges and Obligations

In the year 5121 (1361 CE), Sultan Murad I conquered the great city of Adrianople—called Edirne by the Turks and Endirne by the Jews—home to a small Jewish community that had been living there through the period of Byzantine rule. About thirty-five years later, during the reign of Murad II,1 Jews who had been expelled from France and Germany were, for the first time, allowed to settle in the Ottoman Empire (Togarma). They established new communities in the capital city, and when their numbers grew they sought permission from the state to elect a chief rabbi for all the communities of Edirne, whose jurisdiction would cover all cities of the empire. The first person elected to this position was the German-born Isaac Sarfati, and the post became an inheritance for his descendants.2

On 12 Sivan, 5213 (May 29, 1453), Sultan Mehmed II conquered Istanbul and moved the throne there. He appointed Moses Capsali as chief rabbi of all Jewish communities in the empire; and due to the disagreements between various [Ottoman Jewish] communities, the istanbul-based institution of the general rabbinate did not last for very long.3 Meanwhile, the Edirne rabbinate never dissolved: first it became a local representative of the chief rabbi [of the Ottoman Empire] in Edirne and surrounding towns, and after the istanbul rabbinate dissolved, the Edirne rabbinate became autonomous in its region. As the chronicler4 wrote:

From the day that Ottoman rule was established, the province and city of Edirne have been a light to all surrounding towns [see Genesis 1:16], spreading everywhere the sustenance of Torah. Those who dwell in the city will seek the sustenance of Torah from the mouths [of the rabbis] who perpetuate the rabbinate, which illuminates the land and its people through the generations, in the five congregations of the city and in the surrounding villages5 [ . . . ]

Apparently, the authority of Edirne rabbis in the affairs of their subordinate communities was originally limited. The chronicler wrote bitterly, bemoaning how these rabbis later wanted to interfere in communal affairs beyond their original remit. [ . . . ]

According to these sources, we see that the first chief rabbis of Edirne enjoyed: 1) the right to receive a fixed salary—that could not be challenged by anyone—from every community in their jurisdiction, 2) and these rights were to be passed down to their sons after them. With this came certain obligations: 3) to supply the lulav and other species6 to each congregation, 4) to adjudicate for all congregations that lacked their own rabbis and dayan (moreh hora’ah), 5) and handle gittin [ Jewish divorce law] and halitzot [Levirate marriage] in places that lacked this sort of expertise. In time, the rabbis acquired greater privileges and didn’t want to give them up, which often led to increased controversies within congregations and towns in the province, who the rabbis effectively forced to sign contracts of subordination with them.

Notes

[This was during the reign of Bayezid I. Murad II ruled 1421–1451.—Trans.]

Divre yeme Yisra’el be-Togarmah, Vol. 1, p. 77.

Samuel de Medina, She-elot u’teshuvot, ḥoshen mishpet § 364.

[Mordechai Karmi (1749–1825).—Trans.]

[Mordechai Karmi,] Kovets ma’mar Mordechai, ḥelek nit-pal la-kodesh, p. 182b.

[The four species used as part of the Sukkot ritual: etrog (citron fruit), hadas (myrtle leaves), aravah (willow leaves), and lulav (palm frond).—Trans.]

Credits

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 7.