The Flourishing of Jewish Journalism

This period marks the explosive rise of Jewish newspapers, dailies and weeklies, yearbooks and almanacs, feuilletons and other time-bound printed media throughout the Western world.

From the second half of the eighteenth century, journalism in all forms became the significant medium for the creation of an engaged public, the instrument for debating and shaping local politics and consolidating middle-class identity. This period marks the explosive rise of Jewish newspapers, dailies and weeklies, yearbooks and almanacs, feuilletons and other time-bound printed media throughout the Western world. Newspapers and journals of the nineteenth century disseminated far more than news and advertisements. They kept Jews aware of events affecting other Jews around the world, creating a new vehicle for their collective identity as Jews and as members of a far-flung community.

To cite one example, Shukr Kuhayl II, a messianic pretender, arose in Tan’im, Yemen, in 1868; he was arrested in 1871 by the Ottomans. Primary texts of the movement were published while it was at its apogee, including one set of letters in Kraków. What did the messiah of Yemen have to do with the Jews of Kraków? The letters were likely to have been published by a Galician maskil as a means of satirizing local Jews’ gullibility in following wonder workers. They testify to the power of the press to link Jews from far-flung regions.

As party organs and cultural platforms, periodicals become the forum of choice for a new intelligentsia. Their choices of language, of register, and of audience were politically consequential. Journals served as springboards for writing by Jews not just of opinion and politics but also of belles lettres in Hebrew, in the Jewish vernaculars, and in many European languages. Although political borders in this period shifted frequently, journals employed a common language to unite politically dispersed Jews.

The First Jewish Periodicals

The first European Jewish periodicals appeared haltingly in the eighteenth century (earlier attempts were extremely short lived). With the emergence of the German Haskalah and its subscriber base, however, Jewish journals such as Ha-me’asef (The Collector) and Shulamith became more sustainable. The former was published in Hebrew, with the goal of fostering its use as a literary language among German Jews.

Through the first half of the nineteenth century, German-speaking Jewry remained at the forefront of periodical literature. The medium gradually expanded into the Austro-Hungarian Empire, at first with particular emphasis on the literature and criticism that were hallmarks of Haskalah. By the 1840s, Jews were printing journals and newspapers in Hebrew, Yiddish, and German, as well as in Hungarian, French, Ladino, Italian, Polish, Spanish, and, of course, English.

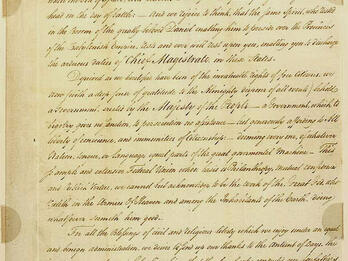

As soon as the number of Jews in the United States reached a critical mass of potential readers, the Jewish press emerged to educate, entertain, and exhort them. Isaac Leeser, ḥazan of Congregation Mikveh Israel in Philadelphia, founded the first successful Jewish paper, The Occident (1843), a monthly. Within a few years, its success spurred several other journals. In 1854, in Cincinnati, Reform rabbinic leader Isaac Mayer Wise established the long-lived and lively The Israelite. American Jewish papers tended to focus on local news and events, and came to be printed not only in English but also in German, Yiddish, Russian, and Ladino, following the needs of each wave of immigrants and increasing in circulation accordingly. Fearful that criticism would reflect poorly on the Jews who struggled to make their place in a new environment, many of the papers presented a relentlessly positive view of their communities.

In 1823, one of the first European Jewish newspapers, Dostrzegacz Nadwiślański (Observer over the Vistula), appeared in Polish, containing articles in German in Hebrew letters and in Polish in parallel columns. It was short lived, possibly because Jews who read and spoke Yiddish had difficulty relating to the Germanized Yiddish, and they may not have been able to follow the Polish-language news. Izraelita, founded in Warsaw in 1866, was the first Jewish newspaper printed in Poland to succeed over several decades. It originally championed the ideal of polonization of Jews; later it adopted a more Zionist posture. A Hebrew-language journal founded by Eliezer Silverman, Ha-magid, appeared in Lyck in East Prussia in 1856. Its formula of moderate enlightenment and conservative religious stance granted it longevity through the end of the nineteenth century.

Periodicals and Political Change

In Russia, the reign of Tsar Alexander II (1855–1881) ushered in an era of great reforms. The serfs were liberated, and the economy began a transformation from rural and agrarian to urban and industrial. Along with these momentous changes, such a stark contrast to the preceding reign of Nicholas I, hope sprung that Russia had finally started on a path of political and social liberalism. Against this background, the need to prepare Jews for the new era stimulated a proliferation of opinions and journals. Five newspapers were founded in the 1860s and 1870s in Odessa alone.

One of the great entrepreneurs of Jewish journalism in the later nineteenth century was Alexander Zederbaum (1816–1893), who championed Russian rather than German as the language of modernization. Adopting the railroad as a symbol of modernization, he urged Jews not to miss the train of modernity. During the 1863 Polish insurrection against Russia, Zederbaum’s newspapers supported the tsar against the Polish rebels, unlike the Polish Jewish papers that supported the Poles. Zederbaum founded Ha-melits (1860–1905), one of the most successful journals, attuned to all aspects of interest for its readers rather than advancing one didactic agenda.

By eschewing the stilted German in Hebrew letters for a more colloquial Yiddish, the paper attracted broad readership from all classes and was particularly noted for attracting women as readers in large numbers. Its pages carried the debates that raged in Jewish society, from questions about migration, about science, and literature to the critical social issues of the day. Indeed, the paper encountered fierce resistance to its reports of social problems, for Jews feared oppressive reaction from the Russian government and people if problems such as poverty and internal discord were aired.

The 1881 assassination of Alexander II, followed by pogroms and mass emigration to the United States, signaled the extinction of hope for liberalization of Russian society and a retreat from the elusive cultural and national acceptance that many Jews had worked so hard to achieve. Despite this dark turn, the extraordinary liveliness of the intellectual exchanges and cultural contributions of the journalistic press made it one of the signal arenas of nineteenth-century Jewish creativity.