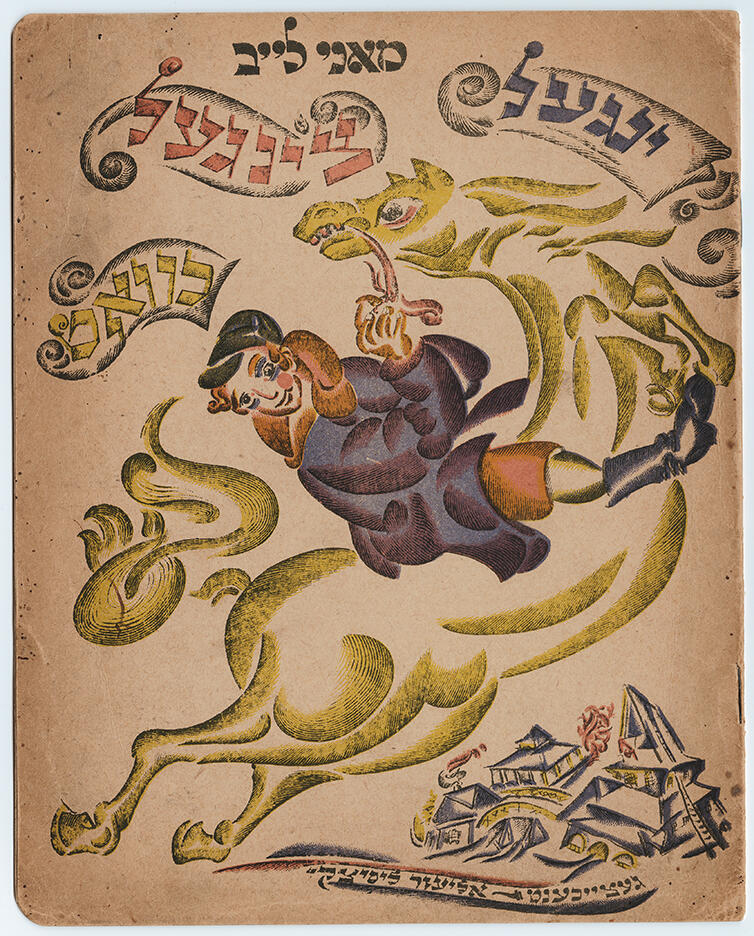

Yingl-tsingl-khvat

Mani Leib

El Lissitzky

1918

Image

Engage with this Source

Creator Bio

Mani Leib

1883–1953

Mani Leib was the pen name of the American Yiddish poet Mani Leib Brahinsky. Born in Nizhyn in the Russian Empire, now Ukraine, he ended his formal education at the age of eleven, when he was apprenticed to a bootmaker. While still in his teens, Mani Leib was twice arrested for revolutionary activities. He emigrated in 1905, spent a year in England, and settled in New York in 1906. He worked throughout his life as a shoemaker. A central figure in Yiddish poetry’s first avant-garde, New York’s Di Yunge (The Young Ones), Mani Leib proved that Yiddish could be used to create poetry of delicacy, subtlety, and beauty. His poetry was remarkable for its sound, using alliteration, cadence, repetition, and sibilance to create effects both of stillness and harmony and of love, joy, and bravado, as in “I Have My Mother’s Black Hair.” Leib also wrote much poetry for children. His weird and joyful story of a fearless heder boy, “Yingl-tsingl-khvat,” became a classic and made its way to East European Yiddishist circles, where it was illustrated by the great cubo-futurist and constructivist artist El Lissitzky in 1918.

Creator Bio

El Lissitzky

1890–1941

El Lissitzky, born Lazar Markovitch Lissitzky in Pochinok, Russia, was perhaps the most brilliant expositor of cubo-futurism and then Soviet constructivism. Between 1915 and 1919, he was an active participant in efforts to develop a new Jewish art in Russia. As a youth, Lissitzky studied drawing with the Russian Jewish painter Yehudah Pen in Vitebsk, pursued architectural engineering in Darmstadt, and traveled extensively in Europe, visiting galleries and sketching buildings and landscapes. During the summers of 1915 and 1916, he participated in the Jewish Historical and Ethnographic Society’s expeditions and was inspired by the extraordinary synagogue frescoes he encountered. Between 1917 and 1919, he drew close to other figures seeking to spark a “Jewish cultural renaissance.” He participated in the first exhibition of Jewish artists in Moscow in 1917, worked with Moyshe Broderzon to create what he called “the new Jewish book,” and supplied illustrations for numerous Yiddish, Hebrew, and Russian Jewish publications, particularly books and journals for children. Beginning in 1919, Lissitzky began to relinquish the idea of creating a Jewish national style and played a central role in developing the nonrepresentational and revolutionary constructivist and suprematist styles. After some years in Berlin, he returned to the Soviet Union. In the 1920s and 1930s, he was an important presence in the world of Soviet art as a painter, graphic designer, architect, pavilion designer, typographer, and photographer.

You may also like

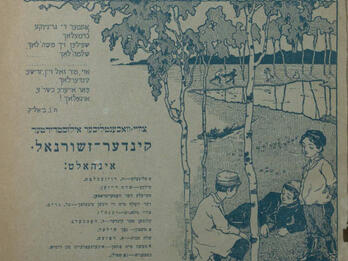

Grininke beymelekh (cover)

Grininke beymelekh (Little Green Trees), no. 1 (Vilna: B. A. Kletzkin, 1914.) The title of this Yiddish children’s journal, the first of the genre to appear regularly, was drawn from the Yiddish poem…

Filke

Berl had no father. His mother was very poor and had to go to strangers to make money for bread. Berl used to stay at home alone, and waited for hours for his mother. He had no sisters or brothers, so…

The Fountain of Judah (Three Stories)

Hillel the Babylonian, the important teacher of Israel, was poor and needy, and his daily income consisted of half a zuz. One half of this he used for food, the other half he…

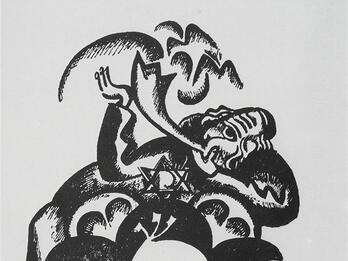

Shloyme ha-melekh (King Solomon)

An illustration by El Lissitzky from Chaim Nahman Bialik’s Shloyme ha-melekh (King Solomon), from an issue of the Hebrew journal Shtilim (Saplings) that was printed in 1917 in Moscow, two days before…

Advertisement for Shtilim, a Hebrew Children’s Journal

We have come together these days, during the awakening of our Hebrew literary sphere, to establish a special newspaper for Jewish youngsters and children.Do we really need to talk at length about how…

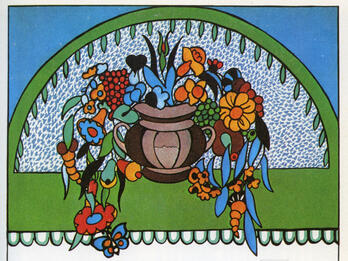

The Wanderings of the Little Blue Butterfly in Fairyland

Illustration from the children’s book The Wanderings of the Little Blue Butterfly in Fairyland, first published in Budapest, Hungary, in 1912.