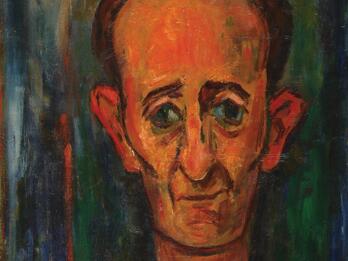

Jacob Fichman

Born in Belts in Russian-ruled Bessarabia (today Bălți, Moldova), Jacob Fichman received both a secular and a religious education. In 1901, he moved to Odessa, joining its lively circle of Hebrew, Yiddish, and Russian Jewish writers, coming under the influence particularly of Chaim Nahman Bialik, a figure whom Fichman venerated and with whom he remained very close. Two years later Fichman began dividing his time between Odessa and Warsaw, the two centers of modern Jewish national culture in the Russian Empire. The early poems that made Fichman’s name were marked by a dreamy Romantic lyricism that opened new vistas of natural beauty and gentle eroticism in Hebrew verse but eventually came to seem limited and perhaps naïve to most later readers of Hebrew poetry. During these years, Fichman, like many Hebrew writers of his generation, began to write extensively in Yiddish as well; more than most of his Hebraist contemporaries, he retained warm feelings toward Yiddish, even participating briefly in the work of the radical Yiddishist Kultur-Lige in 1918–1919 and writing an essay for the first issue of the great postwar Yiddish literary journal Di goldene keyt in 1949.

In 1912, Fichman moved to Palestine, where he edited Moledet, a children’s journal that helped shape the Hebrew culture of Palestine’s first generation of Hebrew youth. Caught on a return visit to Eastern Europe by the outbreak of World War I, Fichman worked closely with Bialik and other Odessa Hebraists to sustain Hebrew cultural life and, from 1917, to engender a Hebrew cultural renaissance in the rapidly changing East European Jewish milieu. Moving to Mandatory Palestine for good in 1919, he devoted himself to the cultivation of the Hebrew literature and culture of the Yishuv, particularly as the editor of Moznayim, the journal of the Hebrew Writers Association, from 1936 to 1942. Throughout his life, Fichman distinguished himself in a variety of genres—children’s literature, textbooks, literary essays, and poetry, including sonnets, idylls, ballads, and narrative poems—and a particular narrative prose often recognized as poetry in itself. His critical essays—on writers that included Bialik, Shalom Yankev Abramovitsh (Mendele Mokher Sforim), and Avraham Mapu—often focused more on their lives than their literary output and seem similarly dated, though they remain an important source for biographical information, particularly about Bialik’s work and thought. Fichman was awarded the israel Prize for literature in 1957.