Sefer yitnu (Book of “They Shall Offer”)

Introduction

It is known that one who lacks books lacks knowledge, for a man’s knowledge is limited in its reach by the reach of his books; and there is no artist without tools. Many new books came from nearby, which are sufficient to set as a precedent of that which came before them, even though the spirit of wise men does not lie within them. They are similar to each other, even though there is a distinction between them, like a hammer that shatters a rock into several different pieces that are not similar to each other. They partake in the disgrace of one’s fellow man, judging him unfavorably in everything, showing the pungency of his critique of the wise men. They have set their mouth against the heavens, and their tongues walk over the earth (Psalms 73:9) through those who sleep in the dust. They speak about them with pride and scorn; for all who decree in this manner are fodder for the nonkosher animals of Israel. Concerning some of them, it is said that anyone who decrees thus increases mamzerim [bastards] in Israel. And concerning some of them, it is said that one who does so rebels like one who is insubordinate. And concerning some of them, it is said that this judgment is not an authority. May the All Merciful save us from these opinions, [b. Shabbat 84b; b. Bava Kamma 65b] and all that come forth from them! The cause of these opinions is that those who formulated them lacked knowledge [i.e., they lacked books], and they did not plumb the depths of Jewish law; and both of these things are the cause.

Wise men who come after them validate the just and condemn the wicked, and they return the divine crown to its ancient glory—each according to their means. There are many things that writers have taken back as a final retraction. Maimonides, too, retracted the judgments he wrote in his commentary on the Mishnah, several times. (This is aside from mistakes of a scribe or of a printing press.) As R. Asher ben Yeḥiel has written [Responsa of Rosh 43:12]: “Blasted be the spirit of those who come to teach from his books.” All the more so if they come to criticize him and do not know the Mishnah or the Gemara, which are the point of departure and the origin of judgment, with the exception of the mistake that the scribe has made between that which is obligatory and that which is exempt, between that which is forbidden and that which is permitted, and between that which is defiled and that which is pure. On account of the insufficiency of their knowledge and also of books, they will not understand the words of the author, and the meaning will be lost on them. In this manner, they turn the words of the living God upside down, and attribute absurd opinions to the author. And even if he erred concerning the matter, who can discern his errors (Psalms 19:13)? For who will say, “My lesson of hindsight is small, I have learned it through and through, and I have not erred”?

Concerning some of the decrees and teachings that they have stated, this matter did not come from a holy authority, but rather was written down by a mistaken student; and they did not want to blame the author. Some wise men have agreed upon many matters of practical Jewish law. Regardless, many have argued about them; they have pushed away their words with two hands—with clear evidence—until they became like individuals against the many. But they do not teach this at all. Many rulings preserved in books, which were the regular practice during the time of the wise men of the Talmud, have been nullified, and are not regular practice at the present time, whether regarding stringency or leniency. There are those that the wise men nullified because a matter was no longer relevant, and thus the decree was nullified. There are others that, even though a matter is no longer relevant, the decree was not nullified, and thus the decree still stands. All that our ancestors were accustomed to do is Torah, whether it is a stringency or a leniency, even if it is against Jewish law. Whoever breaks through a fence, a serpent shall bite him (Ecclesiastes 10:8).

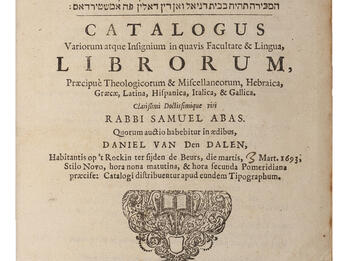

Sometimes there was doubt concerning practical Jewish law, and one would write inclining toward the direction of stringency and would align himself with the stringent; a blessing would come upon such a person, but for others, this is a curse. The money of Israel would be lost, for the Torah would “protect them in a clay pot.” Such a person is permitted to be stringent with himself, but not with others, for just as it is forbidden to allow something that is forbidden, so it is forbidden to forbid something that is allowed. He would stand by his proscription until his friend would come and would make him allow it. Thus, that which is found in one book saying that something is allowed is found in another book saying that it is forbidden. All of this adds to, and goes together with, of the making of many books, there is no end (Ecclesiastes 12:12). Thus, we should not trust a verse from only one book, even if it is from one who was the great one of his generation in matters of practical Jewish law; rather, we should be inclined to follow after the multitude (Exodus 23:2). Every teacher therefore needs to have a sufficient number of books, so that he can be inclined to follow after the multitude in all of the rulings that are accustomed to be performed presently, in these lands.

Credits

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 5.