The Israelite Monarchy from Saul to the Babylonian Conquest

The Israelite monarchy began as a means of uniting the tribes of Israel under the rule of a king chosen by God, but it split into two separate kingdoms after the death of Solomon.

What does the Bible say about the Israelite monarchy?

The monarchy got off to a slow start, facing some opposition; its first ruler, Saul, was a failed king. Yet it was clear that a stronger federation of the tribes, with a centralized administration, was needed if Israel were to grow strong and defend itself against other nations. The monarchy was not a rejection of God’s rule, for God chose the king, through a prophet. David, the second and most famous king, is portrayed at greater length than any other king. He is both heroic and flawed. A successful leader who enlarged his kingdom and brought prosperity, he showed weakness when dealing with his family. He also had adulterous relations with Bathsheba and murdered her husband to cover up the adultery. David’s reign establishes the dynastic principle, meaning that all future kings (at least of Judah) would be from the Davidic line. The dynastic principle was not easily implemented, for several of David’s sons were rivals for the throne, during his lifetime and immediately after his death. Ultimately, the kingship passed to Solomon. He built the Temple in Jerusalem, but his taxation and demands for corvée labor alienated the northern tribes, and his religious missteps alienated God.

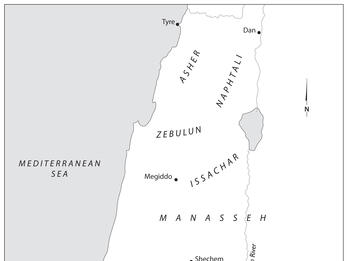

The United Monarchy (with all of Israel under one king) lasted only through Solomon. Under his successor, Rehoboam, the kingdom was divided into the Northern Kingdom, Israel, and the Southern Kingdom, Judah, each with its own king and its own main sites of worship. The books of Samuel and Kings trace the events from the beginning of the monarchy to its end. For the Northern Kingdom of Israel, the end was the defeat by Assyria in 722–720 BCE. For the Southern Kingdom of Judah, it was the defeat by Babylonia in 586 BCE. The book of Kings evaluates the kings of both kingdoms in terms of whether they did what was right in God’s eyes. Ahab and Manasseh are examples of those who did not, and Hezekiah and Josiah are those who did.

In addition to information about the kings in the books of Samuel and Kings, there are stories about the prophets who were their advisers and critics. Most famous among them is Elijah. These prophets were wonder-workers who ministered to the common folk and also had access to kings. They are the predecessors of the classical prophets.

How historical is the Bible’s account of the Israelite monarchy?

The archaeological record concerning the United Monarchy is debated. The remains of building projects in Jerusalem and elsewhere that the Bible attributes to David and Solomon have been found, but archaeologists disagree about whether they were built in the time of David and Solomon—the tenth century BCE—or later, and hence whether David and Solomon ruled over a large state or a much smaller polity, and whether or not Solomon built the magnificent Temple the Bible attributes to him. Recent research suggests that the polity that David ruled may have been more extensive and powerful than the most minimal estimates, a likelihood enhanced by the fact that the stelas of Mesha and Hazael, from about a century and a half later, refer to Judah or its ruling dynasty as the house of David. But assessing the full extent of David’s kingdom and power must await future discoveries.

Evidence for the period following the United Monarchy is more ample. The stelas of Mesha, king of Moab, and Hazael, king of Aram-Damascus, as noted, mention kings of Israel and the house of David. The former mentions Omri and his son (presumably Ahab), and both stelas indicate that Israel had occupied the territory of Moab and Aram since some point in the past. From the ninth century BCE on, inscriptions of Assyrian and Babylonian kings recount their dealings with the kingdoms of Israel and Judah (including some events not mentioned in the Bible), culminating in the destruction of Samaria in 722–720 BCE and Jerusalem’s capitulation to Babylonia a decade before its final destruction in 586 BCE.

Archaeological evidence reveals that the book of Kings gives a skewed picture of the Northern Kingdom. In its focus on the idolatry that it blames for the kingdom’s destruction, the book rarely alludes to the kingdom’s strength and prosperity. Its wealth is illustrated by the palace of the capital, Samaria, whose walls were constructed of what has been called “the finest examples of ashlar masonry from the Iron Age”1 and whose furniture was decorated with beautiful ivory carvings that constitute the largest collection of Iron Age ivories that has been found in the Levant. The kingdom’s military strength is evident from King Omri’s conquest of territory in Moab and later by King Ahab’s contribution of the largest contingent of chariots, two thousand of them, to a coalition of a dozen states that opposed the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III (859–824 BCE) in battle well beyond Israel, at Karkar in northwestern Syria. The book of Kings itself contains an outstanding example of northern literary achievements in the tales of the fabled prophets Elijah and Elisha (1 Kings 17–2 Kings 13). As for Jeroboam’s golden calves—it is not clear that they were actually meant to be other gods, as the book of Kings portrays them; many scholars believe that they were legitimate symbols used in the worship of YHWH, comparable to the cherubs in the Temple of Jerusalem (see Figurines). The book’s distorted view of the Northern Kingdom reflects the political and religious attitudes of its writers, who were from the rival Southern Kingdom.

Notes

Yigal Shiloh, The Proto-Aeolic Capital and Israelite Ashlar Masonry, Qedem Monographs of the Institute of Archaeology 11 (Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1979), 56.