Ancient Israelite Figurines of Deities, Pregnant Women, and Idols

Archaeological evidence attests to the popularity of images and figurines in ancient Israel.

Why are there so many Israelite figurines when the Bible forbids idols?

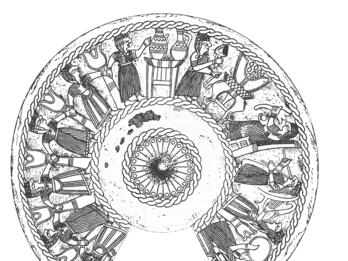

The subject of image making looms large in the Bible, both in the prohibition to make images for worship, as in the second commandment (Exodus 20:5–6), and when this prohibition is violated, as in the golden calf episode (Exodus 32). Non-idolatrous images (i.e., images that were not used in worship) of certain creatures were permitted, such as the cherubs (see Ark of Covenant and Cherubs), the oxen supporting the water tank in Solomon’s Temple (1 Kings 7:25; see The Temple of Solomon) and the apotropaic copper serpent (Numbers 21:8–9). Few, if any, life-size statues of deities from Israel or elsewhere in the ancient Near East have been found, but numerous figurines (in the round and in plaque form) of anthropomorphic figures and animals—and even miniature models of furniture and temples—have been found (for model temples, see Sanctuaries). Particularly numerous are terra-cotta figurines of horses, with and without riders, and figurines of naked females. Many of these bear traces of paint, and it is likely that all of them were originally painted, but over time the color has faded or disappeared entirely. There are very few complete male figurines (apart from the very schematic horse riders who are presumed to be males). But there are fragments (not included in the Posen Library’s collection), such as heads and a fist from male figurines and ivory fragments from a statuette of a seated person. The latter, from Tel Rehov in the ninth century BCE, probably depicted an Israelite king like the paintings and plaque shown in Ancient Israelite Carvings, Dress and Adornment, and Paintings from the Biblical Period. The fist, from the City of David in the tenth century BCE, probably comes from a figurine that resembled one from Ugarit.

What was the purpose of these figurines?

It is sometimes difficult to determine whether anthropomorphic figurines represent gods or humans. Some figurines are identifiable as deities by their material—they are made of or covered with precious metals—or by their hairdo or headdress, their clothing, or an object they are holding. For example, a seven-and-a-half-inch-tall (19 cm) figurine from Ugarit (from the Late Bronze Age, 1550–1200 BCE) that probably once brandished a weapon in its raised hand is identifiable as a deity—presumably Baal—by its horned helmet (known from Mesopotamia as an attribute of deities) and its material, gilded bronze.

Certain figurines of naked females are identifiable as goddesses by features such as lotuses or other blossoms in both hands and the hairdo associated with the Egyptian goddess Hathor, which is parted in the middle and has long sidelocks curving inward at the neck and curling at the shoulders or the breasts. See, for example, the five-inch-high (12.7 cm) Canaanite plaque figurine from Tel Batash (probably biblical Timnah), from the fourteenth century BCE.

Similar plaque figurines of naked women, often with breasts and genitals emphasized or with pregnant bellies, were very common in the ancient Near East. Most were made of terra-cotta and were manufactured in molds. Many have Hathor hairdos or other features that identify them as goddesses. In Israel, plaque figurines of this type persisted into the early Iron Age (twelfth–ninth centuries), rarely later, and primarily in the north. Plaque figurines were ultimately discontinued in Israel and were replaced, in Judah, in the eighth–seventh centuries BCE, by “pillar” figurines. These are figurines in the round that depict the naked torsos of females with their hands supporting their full breasts and, below the breasts, have only a schematic, pillar-shaped pedestal that flares out at the bottom. The pedestal and torso were shaped by hand while the head was made in a mold. Some scholars believe that these pillar figurines, notwithstanding their lack of Hathor hairdos or other attributes of divinity, represent a fertility goddess, while others argue that they represent lactating human women. In either case, these figurines likely served as amulets that represent, and thereby promote, lactation by means of sympathetic magic. They have been aptly described by Ziony Zevit as “prayers in clay.”1

It can also be difficult to determine whether figurines of animals represent natural animals, deities with animal forms, or animals that deities ride or stand on. The four-inch-high (10 cm) bronze figurine of a calf from Canaanite Ashkelon (ca. 1600–1550 BCE) was originally covered with silver leaf (small amounts remain) and was found inside its ceramic shrine (about ten inches [25 cm] high), both of which suggest that it was a deity or an emblem of one, perhaps the Canaanite storm god Baal.

Even when a figurine represents a deity, it is not always clear whether it was an object of worship (as a recipient of prayers or offerings) or a magical amulet or a votive object presented to a deity. Other figurines were functional, used as weights, stoppers, or decorations on furniture and containers, and were probably simply decorative. Some have been interpreted as toys.

Some of the non-anthropomorphic figurines found at Israelite sites had religious significance, especially model shrines (see Sanctuaries). A bull figurine found in the Samaria hills seems clearly to have religious significance because it was found next to a ritual site, but it is not known if it was a deity or the pedestal for a deity. A horse-and-rider figurine from Moza was found in the courtyard of a temple, but its function and that of other horse-and-rider figurines, as well as figurines of birds, other animals, and furniture, is unclear.

Notes

Ziony Zevit, The Religions of Ancient Israel: A Synthesis of Parallactic Approaches (New York: Continuum, 2003).