Women in the Synagogue

Duality manifests itself in all things, but in nothing is this two-foldness more plainly seen than in woman’s nature.

The weaker sex physically, it is the stronger spiritually, it having been said that religion were impossible without woman. And yet the freedom of the human soul has been apparently effected by man. I say apparently effected, for experience has demonstrated, and history records, that one element possessed by woman has made her the great moral, the great motif force of the world, though she be, as all great forces are, a silent force. [ . . . ]

In mother, wife, sister, sweetheart, lies the most precious part of man. In them he sees perpetual reminders of the death-sin, guarantees of immortality. Think, woman, what your existence means to man; dwell well on your responsibility; and now let us turn to that part of time called the past, more particularly biblical days. The religious life of the early Israelites is so closely interwoven with their domestic and political life, that it cannot be separated and treated alone. Amidst all kind of tribal and national strife, the search for knowledge of Javeh went on in so even a way, so indifferent to men and things, as no other investigation has done. The soul of mankind could not be quieted concerning this matter, and religion from its very nature evolved itself.

That this was, in its entirety, due to no one people is just as true as that it was due to no one sex. [ . . . ]

The Talmud speaks of seven prophetesses: Sarah, Miriam, Deborah, Hannah, Abigail, Huldah and Esther. Ruth not being mentioned in this list, we infer that she was regarded simply as a religious teacher. Except in the Talmud, Sarah is not mentioned as possessing the inspirational power, which made the prophets of old; yet, there is that chronicled of her which gives rise to the assumption that, for a time at least, she was the greatest of them all. For in Genesis xxi. 12 is recorded the only instance of the Lord’s especially commanding one of His favorites to listen carefully to a woman: “In all that Sarah may say unto thee, hearken unto her voice.”

Evidently, the Almighty deemed a woman capable both of understanding and advising. [ . . . ]

From any point of view, enough has been recorded to show that when she led, she led successfully. However, the ancient Jewish woman was, above all, wife and mother, and as such she was a religious teacher, and closely associated with what might be called the temple-worship of those days. [ . . . ]

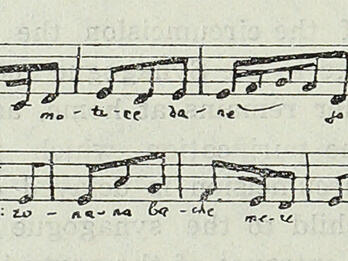

Women of other nations soon learned to contrast the life of the Jewish woman with their own, and the first converts to Judaism were women from the neighboring idolatrous tribes. The emotional nature of Jewish women made them fit instruments to celebrate the joys of heaven and earth, and the finest things in our sacred literature are believed by many critics to have come spontaneously from our women’s hearts and tongues. [ . . . ]

The position of the medieval woman differed from that of her ancient sister. Forced by circumstances at times to become a leader, her personality no longer merged itself in that of her husband, but ran parallel with his. Tribal wars for political supremacy did not now agitate the people, for existence had, in most cases, become an individual struggle. The princes of Judah were dethroned, their lands, the possession of strangers; yet the law lived, better understood and more sacredly guarded than ever. That this was owing, in the greatest degree, to the women is shown by the numbers mentioned in the Talmud as learned mothers and teachers. The Jews were stripped of many precious things by their oppressors, ofttimes their relentless persecutors, yet the Torah held such consolations that the family-home became to the Jew the most beautiful, the most sacred thing in the world. Of the love of a pure wife and reverent, obedient children, nothing could rob him, and he was, indeed, blessed beyond all that sought to harm him. The prophecy of Lemuel’s mother had been faithfully realized; and as we look through the mist of centuries, the sunlight clears grayness, and we read: “Many daughters have done virtuously; but thou excellest them all.” [ . . . ]

With added privileges and numberless innovations, let us see what is the religious status of the Jewish woman of to-day. Compare her with the woman of the Apocrypha we will not, for it would be unjust to both. The one was the result of a great spiritual revelation and chaotic material circumstances pressing against and whirling round each other, leaving as a resultant the keen-visioned, practical woman of the Middle Ages, one whose knowledge was of men, and whose wisdom was of God. Calamitous as were the days, our mothers rose to meet them, each time victorious. [ . . . ]

Centuries have passed; the wilderness is the pride of the world, for it is all a land of freedom, of homes; and the Jew, we find him so grateful that he has well-nigh forgotten to what he owes his salvation. He has forgotten, else how explain the empty temples, the lack of religious enthusiasm, lack of reverence of children for parents, lack of that sacred home life which has made us an honored place in history? [ . . . ]

That we have not possessed ourselves of the wisdom of her who builded her own house can hardly be pardoned us, for what can replace the priceless love which has bound the members of the Jewish family to each other and to their God? Learning is not wisdom. Innovation is not progress, and to be identical with man is not the ideal of womanhood. Some things and privileges belong to him by nature; to these, true woman does not aspire; but every woman should aspire to make of her home a temple, of herself a high priestess, of her children disciples, then will she best occupy the pulpit, and her work run parallel with man’s. She may be ordained rabbi or be the president of a congregation—she is entirely able to fill both offices—but her noblest work will be at home, her highest ideal, a home. Our women, living in a century and in a country which gives them every opportunity to improve, are not making the most of themselves, and to the stranger, the non-Jew, who views us critically, we are not entirely an improvement upon our mothers of old. We may dress with better taste, we may know more ologies, we may discuss high art, but we no longer offer up such reverent homage to the Almighty, as that which was given in times of direst distress and persecution, and which yielded so rich a harvest as an America, in which to enjoy life and liberty to the utmost. How is this liberty enjoyed? Go to the synagogue on Friday night; where are the people? Our men cannot attend, keen business competition will not permit them. Where are our women? Keener indulgence in pleasures will not permit them. Where are the children? Keenest parental examples of grasping gain and material desires will not permit them, and so the synagogue is deserted. [ . . . ]

It is time we stopped calling ourselves chosen, it is time we stopped living upon our past, time we prove we have been chosen a nation of priests by fulfilling His law. Many an one has been chosen for some noble mission who never attempted its completion, and it would be illogical to credit such an one with any great merit. That we are now in the position of backsliders is owing to us women.

Credits

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 7.