Tratado das operaçoens da cirugia (Treatise on Surgical Operations)

Author’s Preface

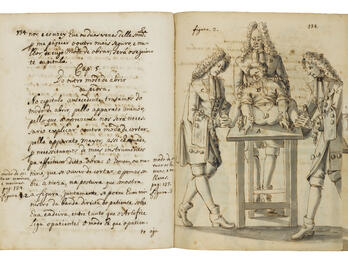

Since the methods of conducting surgical procedures have, for many years, been perfected to the highest degree in England and we do not have any treatise on the subject written in our language, I feel that I have no great need to make an apology for my undertaking. It is true that we have some translations of works written by strangers; however, besides losing much of their merit because their authors do not address the progress that surgery has made among us, their style of describing each operation is full of such superfluous detail and is generally so unpleasant that even when there is nothing new to add to what they have already stated or anything else that could be rejected as false, it would have been better had they been able to treat the same material in a more intelligent and succinct1 manner so as to have a justified reason for delving into it.

In describing maladies, I only mention their evident and distinct signs, and not even once have I dared to speculate as to the particular cause of the animal typology from which they immediately stem. And, indeed, the uncertainty of our conjectures regarding such an intricate nature and the scant usefulness that this kind of speculation can bring to surgery, have completely distanced me from anything that could induce or dispose me in any way toward this type of theorizing. Inasmuch as the greatest devices, till now, have not, through mere hypothesis, served the practice of surgery in any way, but rather have largely distanced surgeons, principally from the study of the symptoms and cure of maladies, subjecting them to futile and useless discourses as well as to a certain style of conversation that has greatly discredited Art among people of good judgment, I hope that no one will blame me for my silence in this regard.

I have taken as much care as I could to make this treatise short, and this is the reason that I do not present case histories, unless the peculiarity of the concept that I wish to establish warrants it being illustrated by facts. Yet, in so doing, I refer to them as briefly as possible. For the same reason, I have undertaken not to reject any practice that I believe would be condemned, and, if the experts of London believe otherwise, I ask that they avail themselves of the books on surgery that are currently the most esteemed in Europe and which I almost always have before my eyes when I criticize generally accepted opinions.

Practically all authors are accustomed to describe extensively the various bandages that are appropriate after each operation. However, since the manner in which they are to be applied is difficult to learn solely by description, and even if this were achieved, there is so little to say on the subject, unless one wishes to copy from others whose example I do not believe worthy of emulating. Moreover, to tell the truth, since the reason one makes use of a bandage is principally to maintain the curative apparatus in place or to compress in certain parts of the body, surgeons always revert to the bandage for these purposes as their prudence and agility dictate, without being at all particular about rules and accuracy in describing what is almost impossible to retain in one’s memory, unless it is constantly put into practice.

In the first edition of this Treatise, p. 99, I stated that the hemorrhaging that sometimes follows lateral surgery has been impugned by an objection of such weight so as to cause the suppression of this operation in hospitals in France by royal decree. Later, I realized that I was mistaken in this matter, for lateral surgery had been prohibited only in the Charité [Hospital] by Monsieur Marechal, the chief surgeon of the king, and inspector of surgical practice in this hospital. What his reasons were for not consenting to have this method continue after its having been practiced by everyone with good success, I shall not take it upon myself to determine.

Notes

The incomparable Newton said that, except for Holy Scripture, he had never seen a large book, especially in the Arts and Sciences, that was good. And the reason for this aphorism was because he was certain that the solid and scientific material of any Art or Science, could be reduced to so little that, if the authors wrote precisely and scientifically, the book would not be large.

Credits

Jacob de Castro Sarmento, “Prefacio do autor,” in Tratado das Operaçoens de Cirurgia (Treatise on Surgical Operations) by Samuel Sharp, trans. Jacob de Castro Sarmento (London: s.n., 1746), XV–XX.

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 5.