Süss Oppenheimer, a Jewish Tale

Chapter 19

When Süss returned to his prison cell, he found his uncle waiting for him. In tears he fell into the arms of the dignified old man and told him everything that had happened to him. Rabbi Simcha comforted his unhappy nephew and turned his eyes toward the Eternal.

Rabbi Simcha rarely left the cell. He had arranged for permitted foods to be brought in for both of them. Süss sincerely repented of his sins and undertook acts of penance. Every Monday and Thursday he fasted, and Rabbi Simcha prayed and fasted with him. The voluntary penance was augmented by another form of torture. Hardly had it become known that Süss would be pardoned, if he agreed to convert to Christianity, when almost every clergyman in the Duchy of Württemberg came to Stuttgart to gain fame and fortune from converting the “stiff-necked” Jew. Every day another cleric came and forced the unhappy man to engage in a disputation with him. On these occasions Rabbi Simcha had to leave the cell so that his presence would not strengthen the prisoner’s resistance. [ . . . ]

No one took the side of the unfortunate Süss and his uncle’s pleas [with the aristocrats of Württemberg whom Süss had once assisted] were ignored. Meanwhile the common people clamored for his death. A rumor was being spread that the devil had taken Duke Carl Alexander and that the Jew Süss was to blame for it. Loudly and threateningly the common folk demanded his execution.

For a whole year the pitiable man remained confined to his cell and for the entire length of time his uncle stayed faithfully with him. When it became clear that all attempts to convert Süss had failed, the death sentence was pronounced.

Süss received its announcement steadfast.

“I am grateful, O God,” he said, “that through an ignominious and painful death you allow me to atone for the sins I committed in my life.”

Then he made his will. Since his uncle strongly refused to accept any bequest either for himself or for his daughter, Süss bequeathed his huge fortune to the communities of Fürth and of Frankfurt. Study houses, synagogues, orphanages, and schools were to be built using his fortune so that his name would live on as a blessing in later generations. We want to mention here right away that of all the bequests not a penny was ever paid to the inheritors. The entire fortune, and even whatever Süss had brought with him to Württemberg, was confiscated. Yes! His murderers proceeded to add scorn to their cruelty. The Jew who had refused to be pardoned at the expense of his faith, the Jew who had dared to rule over Christians for four years, was not simply to be murdered, but his execution was to offer an amusing spectacle for the people of Württemberg.

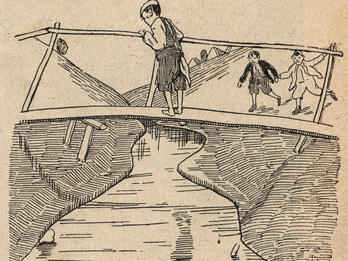

Over a century earlier, Duke Friedrich of Württemberg had kept three alchemists at his court who had promised to transform iron into gold. When they failed, the duke used the iron that could not be turned into gold to build a very tall gallows with a cage at the top, and the duke had the three alchemists hanged there. This iron gallows and the cage at its top were now being painted red. The former prime minister was dressed in a red robe and white stockings and was led to the gallows. An immense crowd gathered to witness this act of revenge and ignominious murder by the courts. Only Rabbi Simcha stayed away; he could not endure to be present at this horrible event. But many Jews from nearby towns had come, not to satisfy their curiosity, but to render to the unhappy man the last service of love by saying the schemos [viddui and Shema‘], the prayers for the dying. They had disguised themselves as peasants and had climbed into the tops of the trees that stood near the gallows.

In his cell, Süss had prayed to God with deep devotion. After he had taken off [the] prayer shawl and tefillin, he embraced his uncle and asked for his blessing—for the last time. His uncle drew him close to his heart and kissed him.

“You do not need my blessing,” he said. “You’ve already atoned for all your sins. Going to your death today, which you could have avoided by denying God, sanctifies you and lifts you above all of us sinful human beings.”

“Still, bless me, Uncle,” Süss pleaded.

So the old man placed his hands on his nephew’s head and said: “May your death be a complete atonement for your sins and may you pass into eternal life.”

Tears choked him and he could not continue. Süss too lost the composure that so far he had sustained by an immense effort and began to weep.

“Thank you, Uncle,” he said, “Thank you so very much for the boundless love and loyalty you’ve shown me. Should your wish be granted and I enter eternal life, I will ask God to pour out the cornucopia of His grace over you and to bless you and your only child so that you may see abundant joy after such bitter suffering.”

Then he kissed his uncle and began to put on the clothes in which he was to die.

“Ha,” he said and smiled when he slipped on the red silk coat, “we are, after all, in the middle of Carnival! In what high spirits they all were at the carnival that I organized at the behest of Duke Carl Alexander. But today is better; I am calmer, happier now than back then in the midst of giddy glee and pleasure.”

He was led outside. Rabbi Simcha stayed behind. When the door closed behind the departing man, his old kinsman fell to the floor overwhelmed by the immensity of his pain, tore at his thin hair, and wept bitter tears.

Calmly Süss climbed into the wagon that was to convey him from the prison to the place of execution. The crowd stood in silence.

When he arrived at the scaffold, a clergyman stepped forward to make another attempt at converting him.

“Be quiet,” said Süss, “and do not poison my last hour.”

Keeping his body perfectly straight, he calmly moved up the steps. The executioner received him at the top.

“Allow me to pray first,” Süss said.

At that moment, many voices arose from the neighboring trees reciting the Shema‘.

Surprised, Süss looked in the direction of the voices.

“These are Jews,” he whispered to himself when he saw the men disguised as peasants sitting in the treetops.

Loudly he joined them in the proclamation: “Hear, O Israel, the Eternal, our God, the Eternal is One!”

At the word eḥad [one] tears were streaming down his face; he felt that he was dying for his unshakable loyalty to the One God.

And again the voices were heard from the trees:

“Blessed be the Name of His glorious kingdom for ever and ever.”

And Süss repeated it word for word, three times.

And then the voices intoned seven times: “Adonoi hu Elohim, the Eternal is God!”

And when the last sound had vanished, Süss expired, releasing his soul that in life he had so often soiled and whose many sins he had expiated through his long suffering in prison, through steadfast loyalty and a heroic death.

Credits

Marcus Lehmann, Süß Oppenheimer: Eine jüdische Erzählung [Süss Oppenheimer: A Jewish Tale] (Mainz: Wirth, 1897), pp. 128–33.

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 7.