Spanish Translation of Judah ha-Levi’s Kuzari

Do you think languages are eternal, and have no beginning?

They are invented and instituted by common consent, rather than natural; this is evident from their composition of nouns, verbs, and adverbs, these being composed of letters, which are articulated in distinct pronunciations; and if they were natural, there would be only inarticulate sounds like those of irrational animals.

Commentary

The Ḥaver—after having demonstrated the truth of the world’s creation, based on the news that the children of Israel learned from our teacher Moses, as well as on their fathers’ tradition; and the king having confessed that it was not possible to be persuaded to believe a falsehood regarding the origin of the world’s well-known nations, nor regarding their possessions and their languages, from a history less than five hundred years old—now shows him that human beings had a beginning, and that they were not eternally engendered by other men (as in the philosopher’s false opinion), as reason makes clear. So then he asks the king what he thinks about languages, if there is any reason to believe that languages are eternal, in which case they would be natural, whereas if they were invented, inventers must necessarily have preceded the languages, and they would not be eternal. The king responds that languages must have been invented and that it cannot be argued that they came naturally to humankind. The Ḥaver asks if he has ever seen or heard of someone who invented a language. The king replies that he has neither seen nor heard of such a person, but that there must have been a time in which languages were invented, with distinct peoples adopting the particular language that they invented and that was newly introduced among them; before that, they had no language. And since it is true that languages were invented, human beings were necessarily created; and as languages were invented, the inventers must necessarily have preceded languages. And if they previously had another language, it also had to be invented, and the inventers had to exist prior to that language; but it cannot be argued that in this fashion they had one language before another ad infinitum, since it cannot be that a whole nation agreed to change its language for no reason; nor have we ever known languages to change like that—inventing a new language and abandoning the one they had. The result would be great harm to their descendants, who would be unable to understand the books of science and practical teaching that their ancestors had composed in another language, for which reason it cannot be that an entire people consented to change their language for another new one. And so, because languages are invented, it is necessarily true that they were invented in a time when they had no language. And therefore, human beings could not have been eternal, with no beginning: they must necessarily have language, their means of communication, for their preservation; it follows then that since languages are invented, humankind had a beginning.

Translated by

.

Credits

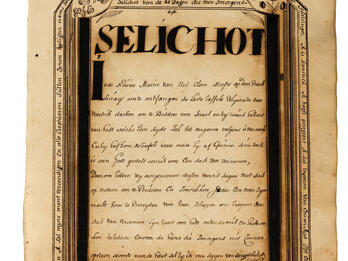

Judah ha-Levi, Cuzary libro de grande sciencia y mucha doctrina, trans. Yehudah ibn Tibon and Jacob Abbendana (Amsterdam, 1663), 19–20.

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 5.