Megilat evah (Scroll of Enmity)

I had been living in tranquility in my home, refreshed in my sanctuary, my palace, in the holy congregation of Prague for some twenty-eight years after they had chosen me from the assembly to be a leader over them, and a judge among the teacher judges, like one of the mighty ones who fight the battles of Torah, whose rulings decide every great and difficult case. In addition, Torah study never ceased from my house and my table from the day I became a man. I set aside a specific room in my home, where I made a safeguard for my charge [see, e.g., b. Yevamot 21a], as I had many study groups, so that day and night their lips never ceased from learning, while I was like their head and eyes. I also possessed much silver and gold, and books that are more desirable than fine gold [see Psalms 19:11]. [ . . . ]

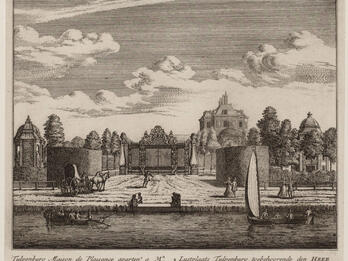

Now, in the month of Heshvan 5385 [1624], I was selected to serve as head of the court and rosh yeshiva in the holy congregation of Mikulov, in Moravia. All of its residents are wise, intelligent, and men of valor; may the Lord increase them many times over. In the month of Adar of that year, I was chosen to be head of the court in the city of Vienna, the capital of Austria, a city full of Torah, wisdom, wealth, and honor; may the Lord increase them many times over. Everyone knows the fine improvements I made, and their constitution I enacted, for it was then that they became one community, whereas beforehand they were scattered among the gentiles, each group separately; they were not a united assembly. Eventually, our lord the Caesar, may he be exalted, gave them their own place outside the city, and he also built a synagogue with turrets (Song of Songs 4:4) for our prayers and all the other local communal requirements. I held those Jews in great esteem, and the feeling was mutual.

In the month of Tevet 5387 [1625], I was chosen to serve as head of the court of the holy congregation of Prague, a very large city. Since I was already there, as stated above, I decided to settle down. Although the Viennese congregation wanted me to stay, and offered me a lot of money and additional honor and pomp, I wished to live nowhere else but Prague. After Purim, I traveled from Vienna with great honor and laden with many presents from the community, apart from gifts given by individuals, as they had observed and knew how I had served them full-heartedly. I bid them farewell in the presence of a large company and with tears flowing down both their cheeks and mine, like the separation of a father and son. As the sages have stated: your departure is difficult for me; “anyone who separates from you, it is as though he has separated from life itself” [b. Kiddushin 66b].

When I arrived in Prague, at some point during the month of Nisan, I was received with great honor, and all the wealthy members and leaders of the community came out a day’s journey to meet me, while some special individuals traveled for a few days toward me. [ . . . ]

I did not believe it when they told me and warned me: “there is a conspiracy; not only against the leaders but also against you.” For I was absolutely certain that I had not defrauded or oppressed anyone [see 1 Samuel 12:2], and that no injustice had been performed at my hand. However, I am a worm and no man (Psalms 22:7), and even King David, may he rest in peace, had deceitful enemies and people who hated him for no cause—how much more so myself, a lowly, despised fellow, unworthy and undeserving of being mentioned and listed together with even the servants of our master David, may he rest in peace.

Now, on Monday, 4 Tammuz, 5391 [1631], toward evening, at the time of the afternoon prayers, a certain man, a Jew, approached and informed me that the imperial minister and judge had inquired whether I was at home, and that he had a secret matter to tell me. That man had replied that he does not know and said that perhaps he is in the study hall, learning in the yeshiva, as is his wont. That man further told me that he had said to that judge, “why should the master come to the rabbi? If the rabbi is informed that the judge wishes to speak with him, let the rabbi come to the master’s house to hear what he has to say.” The minister responded, “No; I will come to him.”

Frightened by this report, I went to the synagogue, and when I left for home I gathered around me leaders and good people—may their Rock protect and sustain them—and related to them all that happened. Meanwhile, the imperial minister and judge traveled in a covered wagon to the house of a Jew who lived almost opposite my own home, where he stayed for about half an hour in the night. Then he arrived at my home, to the upper story where I was living, and sent word to the winter house, asking permission to come into my room, and we replied that he may come. He entered and extended his hand to each and every one of us, with a smile on his face. I had already prepared two chairs, and he sat me to his right, with himself to my left. He sat alongside me and we discussed rumors of different kinds. Then the master said to me, “I have a secret matter to tell you” [see Judges 3:19]. I accompanied him into a chamber that was within the room designated for my studies, for I had been informed by the holy congregation of Vienna on that day that the Caesar, may he be exalted, had commanded his deputy in Prague to transport me there in iron chains.

Credits

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 5.