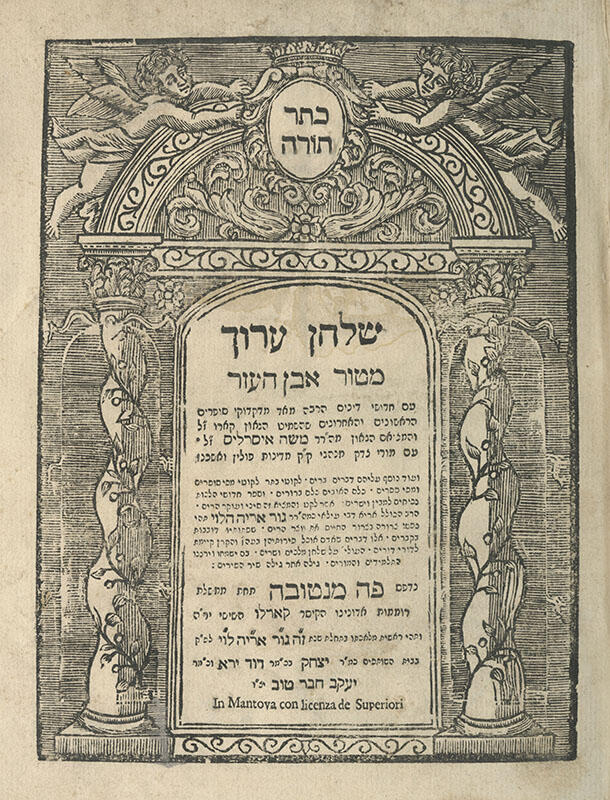

Mapah (Tablecloth) to Shulḥan ‘arukh

Preface

Says Moses, son to my Master, my father, R. Israel—may the memory of the righteous be for a blessing for the world to come—seeing that the illustrious author [Joseph Karo] of the Bet Yosef [The House of Joseph] and its Shulḥan ‘arukh [Set Table], a sage greater than a prophet, has slaughtered his victuals and laid out his table in such array as to leave no room for anyone to gain further preeminence through it, save by collating the statements of the later authorities and by indicating the customs adopted in these lands, I have come in his wake to spread a tablecloth over the Shulḥan ‘arukh composed by him, upon which are all manner of delectable fruits and tasty dishes, beloved of man independently of this table, laid out by him before the Almighty and which have not yet been offered to the people in these lands, as most of the customs of these lands do not accord with his views. For our sages of blessed memory have already declared [b. Eruvin 27b]: “We may not derive [fresh halakhah] from general principles, even where the expression ‘except’ is employed.” And a fortiori from the rule laid down by the aforesaid illustrious gentleman himself—i.e., to decide the halakhah in accordance with Isaac Alfasi and Maimonides in cases where most of the later authorities disagree with them, as a result of which there are numerous statements scattered throughout his works that do not conform to the halakhah according to the words of those sages whose waters we drink—the decisors renowned throughout Ashkenazic Jewry—who always served as our constant guide and from whom they determined the halakhah, the really ancient ones—Or Zaru‘a [Isaac ben Moses of Vienna], The Mordechai [ben Hillel], Rosh [Asher ben Yeḥiel], Sefer mitsvot gadol [Great Book of Commandments, by Moses of Coucy], Sefer mitsvot katan [Small Book of Commandments, by Isaac of Corbeil], and Hagahot Maimuniyot [by Meir ha-Kohen of Rothenburg (ca. 1260–1298)]—all based upon the statements of Tosafot [a set of medieval glosses on the Talmud] and the French sages from whom we are descended. And I have already elaborated on this, praise the Lord, in the preface to my work where I took issue with the illustrious Karo—long may he live, preeminent in everything he says—and perceived that all his statements in the Shulḥan ‘arukh are as though they had been given from Moses’ mouth, from the Almighty, so that students will follow in his footsteps and imbibe his words without dissent, as a result of which all the customs of the various lands will be unified. However, our sages of blessed memory have already declared that many practical differences existed between Eastern and Western Jewry even in the early generations, and a fortiori in these later times. Hence I saw fit to record, alongside, the views of the later authorities in such instances where his statements appeared unsatisfactory to me, so as to alert students everywhere to appreciate that what he has stated is the subject of debate; and wherever I know that the custom does not accord with his views, I shall explore the issue and discover the truth. I shall record: “This is the custom” and place this alongside [the Shulḥan ‘arukh’s ruling]. And despite their statements being vague and cryptic and possessing no value as against those of the illustrious gentleman, insofar as his statements in their entirety are to be found in his magnum opus, the Bet Yosef, I have nonetheless followed in his wake in recording the statements in a general manner, for in most cases my view is also to be found mentioned in his work, and the researcher may choose whether to adopt it; and should he not find it in his work, he should explore thoroughly among the statements of the later authorities which have variously become disseminated throughout these lands, and he will find what he seeks. For I have added only a very few of my own views, and have in such instances stated: “Thus it appears to me” to indicate that the words are my own. And I trust in the Almighty that my lengthy statements will also become spread throughout Jewry, for heaps upon heaps of proofs, reasons, and arguments on every topic are to be found there, to the utmost extent of my capability. And he who has a discerning palate will be able to taste the dishes himself by their own flavor and will not rely upon others, while he who has not yet attained this level should not deviate from established custom, as the aforesaid illustrious gentleman has himself stated in the preface to his great work. And accordingly, I shall render praise to the God of my salvation, and continually bless His name for having magnified his kindness toward me; and I request for the future that He should not forsake me nor cast me off now and forever. And may he agree with my words at the time I utter them and protect me from error, as it is stated: The Lord guards the simple (Psalms 116:6), and guide me as to the path I should follow, for unto Him have I lifted up my soul. Now may the graciousness of the Lord our God be upon us, and establish the work of our hands upon us—yea, establish our handiwork! May He who dwells in secret on high, guard us and make us worthy of being granted the Psalmist’s request: You prepare a table before me in the presence of my enemies. You have anointed my head with oil; my cup runs over. Surely goodness and mercy shall pursue me all the days of my life, and I shall dwell in the house of the Lord forever (Psalms 23:5–6). Amen.

Translated by

.

Credits

Moses Isserles, “Preface” in Mapah (Tablecloth to Shulḥan ’arukh) (Kraków, 1570).

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 5.