Isadora Duncan

1905

“Miss Duncan? The dancer? What is that—ballet?” No, it is not ballet. Missing here are the two predominant elements that make up modern ballet: there is neither dance technique nor women wearing tights. Or, more correctly: there is technique and nakedness, but missing is their prevailing impression.

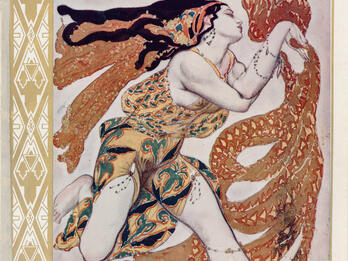

She appears, timid and naïve, to the strains of some classical musical work. She is barely dressed. She is wearing a short, transparent tunic with slits down the sides; she is barefoot. A moment later no one remembers whether she is dressed or not. “A statue is never naked,” says Turgenev’s “man in the gray spectacles.” Other impressions, infinitely more spiritual, completely eliminate and exclude any impression of crude nakedness. You forget about the woman and remember only the human being. She is protected from dirty thoughts and the lascivious gaze by something immeasurably more reliable than a dress.

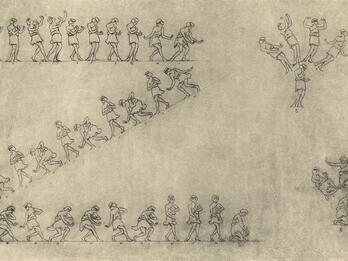

They’re playing Chopin. She comes out sort of sideways, with a certain awkwardness, as if she were seized by the mood of the musical work, drawn into its rhythm and movement. It is not always what we call dance: it is various poses, transitions, movements, and a play of mimicry and gestures. You see that all this is supposed to interpret the music. You may not agree with this interpretation; you may understand the mood and content of Chopin’s prelude in a different way; but you see that this dancing is precisely an interpretation of the music and not movements connected to it by chance. It is a mimical illustration of the music. If music can illustrate a poem, then dancing can clarify music. But one can demand determinacy from this interpretation only to the degree that one can demand it from music.

The variety of her devices is stunning; their beauty attests to the extraordinary height of her technique. Anyone who knows the life of art understands that beauty like this comes at a price. The overall impression holds not a shadow of artificiality or premeditation, though. It is as simple and immediate for the viewer as is life itself. In the scherzo of Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata” she leaps and waves her arms like a child, like a simple young countrywoman brimming with an excess of vitality. She acts out this naïveté, this joyous fullness of being; this is her role, but you are gripped by the lofty truth of this depiction. These moments of Bacchanalian ecstasy seem among the best images Isadora Duncan has created, although this may be a matter of mood. She knows how to be imperiously invocatory and powerful, her entire being merging with the revolutionary mood of Chopin’s famous insurrectionist polonaise. With a barely perceptible movement of her body and arms she suddenly adopts a pose of such infinite submission to fate that a more powerful artistic depiction of all-encompassing Fate is scarcely conceivable. She is bold in her movements; she allows herself to be clumsy and angular when the truth so demands, though her entire aspect does not cease to be infinitely graceful as a result. This is how elegant and beautiful people are in the legend we have created of the distant past, the legend of the ancient Greek world. This is how beautiful they will be in the resplendent future. This is why the art of Isadora Duncan—like any genuine art—is a prophetic art. It was about her that Gleb Uspensky1 uttered his marvelous words about the artist and creator of the Venus de Milo: “He needed to stamp the tremendous beauty of the human being on our hearts and minds, for eternity, indestructibly, to introduce the human man, woman, child, and elder to the sensation of the happiness of being a human being, to show and gladden us all with the possibility—visible to us all—of being beautiful.” Isadora Duncan’s art creates this idea. And she, like the naked goddess before whom Heine wept and Gleb Uspensky bowed, “draws in our imagination the infinite prospects for human perfection and human futurity and infuses in our hearts true grief about the imperfection of today’s man.”

Like any genuine art, the artistic forms created by Isadora Duncan not only surpass the bright future but also bring it closer. For her art is also “thinking in images.” It offers new means of expression, new means of interaction, new means of mutual understanding. [ . . . ]

1907

Yesterday, “to the imposing sounds of Gluck’s melodies,” to which—Turgenev imagined— “slender shadows pass through the Elysian fields without sadness or joy,” the dancer Duncan revealed to us not the world of death but the world of life, infinitely full, mighty, and beautiful.

We have forgotten about human beauty. We don’t know how to believe in its integrity. We know only its fragments. We admire beauty of thought, and we greedily seek out moral beauty and worship the beauty of the great deed. We are not simply indifferent to the beauty of the body: racked and embittered, we have pushed out our simple, healthy, powerful attraction to it with our age-old vehement denial of it. An entire world of culture stands between us and beauty; our entire past, all our searchings, repudiate it. It doesn’t matter whether they assert it theoretically or deny it: psychologically they push it away. We have a sensitive conscience; we are supposed to have a sensitive conscience: how dare we recall something not fit to be used as a plaster! We have forgotten about beauty. We knew there was a human world that achieved it in living embodiment, but that world has receded so far from us that only for a choice few of us, at select moments, do the precious remnants of its art give birth to its vital sensation.

Duncan’s art speaks of this world of forgotten but possible beauty. Specialists do not like her dancing; specialists like serenity, intellectual and otherwise. Morality specialists say that the dances of this barefoot woman are of no use because there will not be any fewer hungry people in the world as a result of her dancing; rather, there will be more. Music specialists are horrified by the fact that she “dances” Chopin nocturnes and Beethoven sonatas. Ballet specialists are indignant over dances without tutus and the traditional conventions. Fig leaf specialists are shocked by her bare feet, in which they see nothing less than an assault on good morals. The tragedy of specialists, as we know, lies in their one-sidedness; there is so much they don’t see, often they don’t see the main point, and here they see nothing.

What is there to say about her dancing? It is an inexhaustible, invincible stream of beauty, naturalness, and purity, bewitching and imperious, drawing one into its magical life. It is a full, exhaustive expression of the human being in all his natural elegance, in the divine vitality of his movements, and in the beautiful spirituality of his outward form. Isadora Duncan does not dance—dancing takes up no more space in her movements than it does in the soul of the young woman she is depicting—she just lives. If she moves in rhythm, then that is because rhythm is the natural form of every beckoning of her body; she is rhythmic, too, when she is still. An unusual naturalness puts its stamp on every bend of her body, every device of her marvelous acting. And then—what purity. Here before us is a woman, barely dressed, half-bared; her light clothing billows in her frenzied, Bacchanalian dancing, revealing her nakedness, and it is impossible, inconceivable that for a healthy person this gripping aesthetic pleasure might be complicated by any sexual element, which would rend the vital fabric of artistic knowledge.

All this, naturally, is not the consequence of some primitive naturalness or elemental purity. It is the result of high art. It is a genius’s art, not raw essence. It is the conscious creation of an ideal thoroughly felt and thoroughly considered. In it—and in it alone—is the discovered secret of life, in it is that “possibility—visible to us all—of being beautiful,” which alone holds the illumination and consecration of earthly existence. I have already cited these words of Gleb Uspensky with respect to Duncan’s dancing and can once again only recall what the great, suffering creator of moral values experienced before the snow-white nakedness of the marble Venus de Milo. In her he saw the immense, eternal beauty of a human being, possible, essential, and achieved, and he understood that “there is no point living if one cannot feel this at least once in one’s life.”

This feeling is given by Isadora Duncan’s divine artistic splendor. One can go on living. One should go on living.

Notes

[Gleb Uspensky (1843–1902), a progressive Russian intellectual and writer.—Eds.]

Credits

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 7.