Ḥavvot Yair (Villages of Yair): A Curriculum of Study

[Question:] A certain gentleman, a close and trusted friend, a Torah scholar who had read scripture, learned Mishnah, and ministered to many learned talmudic scholars, invited me to come to the holy community where he lived, the holy community of Worms, for the bar mitzvah celebration of his only son, on Shabbat Beshallaḥ, at his expense. And although he pressed me hard, by letter, also hinting to me about settlements and gifts, I set his pleadings aside.

He wrote to me again, basking in the glory of the great feast that had taken place, and telling me that the greatest men of the community had been present, and that not one of them had remained at home, but had all gathered together for his joyous celebration. He further mentioned that he was genuinely annoyed that I had absented myself, but that I could atone for this by advising him, given that this only precious son of his in whom all his future hopes lay, and for whose sake he had invested all his trouble and efforts—who was a receptacle admirably suited for Torah study and had delivered a delightful homiletical discourse at the banquet—what his studies should include, and what work he should choose for his initial object of study so that the divine purpose might succeed by his hand (Isaiah 53:10). For many people were telling him that he should learn a page or two of Talmud daily, and many were saying he should study the [Arba‘ah] turim, while some were suggesting the Sefer me’irat ‘enayim—and that he was now inquiring from me and casting his burden in this matter upon me [see Psalms 55:23], assuring me he would follow my opinion and advice and reject all other views.

[Answer:] This is what I replied, having initially written many other things to him, “Now concerning your request that I advise you on the curriculum of study for your only son, whom you love, you ought to have informed me which books he has already studied and is proficient in. However, as you have informed me that he delivered a beautiful homiletical discourse, I imagine that he has already learned words of aggadah, like Midrash Rabbah and the ‘En Ya‘akov, as these are indeed excellent for young men as hors d’oeuvres before the main meal, and are also deemed glorious and majestic by those hearing any literal or allegorical interpretations from him, or they may enable him, when present at the discourse of a great scholar to interject aloud and display his knowledge and comprehension [of the relevant material], so there is a certain beneficial element in this, in that he will be able to acquire himself a reputation as an exceptionally learned man. With all this, he will perhaps be able to find a wife and find goodness [see Proverbs 18:22], and abundant wealth, despite the fact that this is not the correct direction to be taken by the authentic Torah scholar, who has acquired wisdom and has ascended and become elevated so we can expect him to impart halakhic teachings, and good and upright laws in Israel, and whose soul is replete with “meat and wine,” namely the fundamentals of the Torah. [ . . . ]

Now it is exceedingly difficult to recommend certain topics of study and to discourage others, as they are all beloved, all flawlessly pure, and all standing at the zenith of the world, and the aim is to bring about the ultimate objective, the perfection of the soul. Far be it from me to say that one subject of study is fine and another is not. It is simply that just as the most fundamental aspect of any branch of science is to follow the correct sequences and progress by stages, so too the same applies in grasping the wisdom of the Torah. For assuredly there is no better object of study than that of Talmud, but it is an exceedingly lengthy journey. If one learns, in conjunction with the Gemara, Rashi, and Tosafot, as designated for the general schedule of study there [in the academy], an extra page of the Talmud, that is more than sufficient, even for a distinguished student, should he desire to retain his learning and to hunt his prey [see Proverbs 12:27], without it slipping from his grasp in the wind. It should then take him several years fully to master four or five large tractates.

And as for the study of the Turim and the Sefer me’irat ‘enayim, I have seen many of the young men erring in this regard, as they listen to a daily discourse on these books, but these are not useful for general purposes, merely for the laws relating to monetary matters, which, in regard to logic and precision, represent the most advanced portion of learning. Now, far be it from me to belittle the virtues of the laws of God, for they are vibrant and emanate from a sacred source. [ . . . ]

Now in our generations, the choicest and best part [of the Shulḥan ‘arukh], the Oraḥ ḥayim, whose essence is, as its name suggests, “the Path of Life,” sits bereaved and in isolation, with no one paying it any attention. [ . . . ]

See further the Sefer ‘ikarim, dictum 1 at the end of chapter 3, as it is relevant to our enquiry here, that, in regard to Oraḥ ḥayim too, it is obligatory for every Jewish man to be acquainted at least with its general principles and the majority of its detailed laws; and this is the choicest part of learning, concerning which our rabbis of blessed memory taught regarding one who learns for the sake of fulfilling the commandments, that he will be granted an opportunity [to learn, teach, observe, and perform] [see m. Avot 4:5].

Now it is acknowledged that the fruit of all study is action, even though study of the divine Torah in its own right is elevated far above any deed, in accordance with the exposition of our rabbis of blessed memory [b. Mo‘ed Katan 9b] on the verse All desirable things cannot be compared with it [i.e., Torah] (Proverbs 8:11).

In any event, without doubt, study that leads to good deeds has a special, multiple virtue over any other form of study. [ . . . ]

Learning the art of grammar in moderation is excellent, and it is obligatory for any rational person to be acquainted with the general principles, whether in relation to singulars and plurals, masculine and feminine, past, present, and future tenses, direct and indirect speech, and the auxiliary letters and their positions. But to spend one’s days on irregular conjugations noted by the grammarians—this is totally unnecessary. Similarly as regards the accents: the dagesh [strengthening of a letter] and the rafeh [softening of a letter] and the general rules in relation to these, it is obligatory for a man—insofar as he is a man and a “living soul,” in the sense of the Targum [to Genesis 2:7]—to have knowledge of these. [ . . . ]

However, one ought not to waste time on acquiring knowledge of all the minute details and matters derived from the general rules, for knowledge of these creates great confusion with little real benefit. And there are those who apply to this matter R. Eliezer’s dictum: “Keep your children away from logic (higayon)” [b. Berakhot 28b].

Now concerning the study of Mishnah, it is excellent that a man should accustom his son, from the time he attains the ability to understand the halakhah in the majority of the Talmud, that his teacher should learn with him one chapter of Mishnah daily, and half a chapter when it comes to the difficult and lengthy chapters. He should further ensure that he continually reviews them, without negligence and lethargy. He ought easily to be able to undertake this in conjunction with the study of Gemara, Rashi, and Tosafot, and it will be highly profitable and useful for all his subsequent studies, especially now that we have merited to have the commentary of R. Ovadiah of Bartenura, which is like a veritable Talmud. [ . . . ]

But in those generations the words of the Mishnah were not written down, and it was prohibited to write them—moreover, there was no printing, which was invented only about three hundred years ago. Consequently, they required a great amount of time for the study of Mishnah; and in any event, the teachers certainly did not start learning with their pupils the finer points and niceties of the Mishnaic texts and any novelties deducible from the problems raised therein and from unusual phraseology, until such time as they had learned through the entire Mishnah, or the major part of it. And it can be shown from the five years [of a child’s life specifically devoted to study] of scripture [see m. Avot 5:22] that they used to learn the entire Bible with their sons before commencing the Mishnah.

And accordingly, my illustrious master, my father (may the memory of the righteous be for the blessing of eternal life) learned with me daily a chapter of Mishnah in conjunction with my studies at my teacher’s home, until I attained young adulthood, when I would read the Gemara with Rashi and Tosafot throughout the Talmud, which roughly coincided with the time of my father’s arrival at the holy community of Worms at the end of the year 1650. He would then study with me and with friends—outstanding young men—the work of the Rif [Isaac Alfasi (1013–1103)] with a small selection of his writings, this being the good and correct path, leading to practical results, over and above all other types of study, and so the greatest intellectual giants of yore were accustomed to do.

[ . . . ] If you support my stance, and are willing to listen to what I say, do not let your son spend his time on hair-splitting distinctions and pointless wit-sharpening exercises, which, on account of our many sins, have become widespread. [ . . . ] This is something we encounter nowhere in the words of the ancients—neither in the Gemara nor in the Tosafot, even though they [the Tosafists] could uproot mountains. Indeed, our greatest authors have cried out in complaint against these. [ . . . ] My grandfather, our illustrious teacher R. Leib of Prague, who delivered discourses in Posen in 1593, spoke about all of these, and I have neither seen nor read of anyone praising such methods. [ . . . ] It is fitting to lament bitterly at their choosing to waste time on such exercises—sometimes the major part of the day—when we would be able to learn and teach several pages of the Talmud and the halakhic authorities. Rather, you should accustom your son to scrutinize most carefully the text of the Gemara, Rashi, and Tosafot, in regard to omissions, superfluous expressions, and changes, both there and elsewhere. This is the authentic type of acumen to which the ancients, the compilers of the Talmud and its commentaries, were accustomed.

If you do not know the footsteps of the sheep, go forth and graze your kids among the dwellings of the shepherds [see Song of Songs 1:8].

Now, as the outstanding scholars among the later authorities have already spoken about this, and I too, who am but dust and ashes (Genesis 18:27), the poorest of my clan [see Judges 6:15], have written on this topic in several places, I shall not elaborate upon it. But I believe my words will enter your ears, and if you pay attention to me, in conjunction with prayers to the Giver of the Torah and of wisdom, then both you and your son will achieve success in your ways and become wise.

By your lives and the life of the one who wishes you well.

The heavily occupied

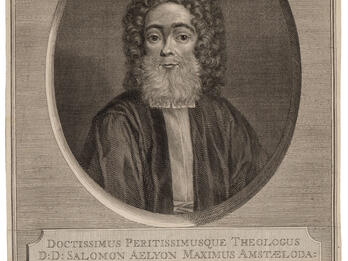

Ya’ir ḥayim Bacharach.

Translated by

.

Credits

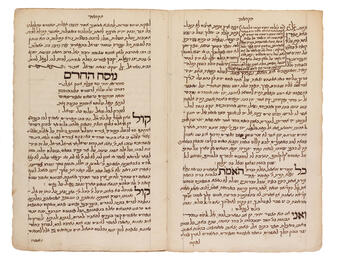

Yair Ḥayim Bacharach, “A Curriculum of Study” (responsum, Worms, 1699). First published as: Jair Ḥayyim ben Moses Samson Bacharach and Moses Samson ben Abraham Samuel Bacharach, Ḥavat Ya'ir (Villages of Yair) (Frankfurt: Bi-defus Yohanes v'ust, 1699). Republished as: Jair Ḥayyim ben Moses Samson Bacharach, Sefer she’elot u-teshuvot Ḥavot Ya’ir (Lemberg: Bi-defus A.Z.V. Salat, 1896; repr., Jerusalem, 1987), no. 124 (?).

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 5.