Don Carlos at the Turn of the Century

A Comedy of Thieves

Who is coming? What do I hear! God Almighty!

[Markwitz standing in the door.]

Markwitz, tall, thin appearance. Threadbare elegance of the nineties. He is, without a doubt, a Hebrew, but dislikes admitting to it. Besides, he has already undergone baptism several times, though without noticeable advantage to himself. His nose shows the bold curve of the Chosen People. It is white and mighty and constantly in a sweat. Beneath that nose a mustache bristles against the es-ist-erreicht form1 that has been forced upon it. His tongue is quite offensive,2 his mode of speaking guttural and the legs, too, are not above reproach. When they walk they talk Yiddish. There is something extraordinarily greasy to his nature and he coats all his words with schmaltz [goose or chicken fat], so to speak, and does it with deep pleasure. He has an unusually favorable opinion of himself and considers himself the archetype of a beautiful German. [ . . . ]

Well, my mother [pointing to the bed].

[Markwitz walks toward him, questioningly.]

She fell. [Pained, heavy pause. Then brooding gloomily.] And, furthermore, I fell so low that I must remind you to satisfy the long forgotten debts.

Markwitz [Deeply embarrassed]:

Oh, be quiet, Karle, about these childish stories. [Distracting.] As the delegate of all humanity of Posen I am coming here. It is the provinces of Posen that solemnly besiege me to apply myself on behalf of their salvation. And my hour has already come!

[A clock chimes half past nine. He pulls out a watch.] [ . . . ]

[Karle wants to hold him back].

I want it, want it! So hurry!

[Karl moves to the side, removes the bed screen.]

[Mother sits up in bed, her head is bandaged.]

Markwitz [Very elegantly, sleek and striking]:

I am from Posen, Markwitz is my name.

[Thick, greasy pathos.]

As the delegate of all humanity,

I come from Posen. It is the provinces of Posen

that solemnly besiege me to apply myself

on behalf of their salvation.

Yes, an oppressed heroic nation is sending me,

the last hope of these noble lands—

the exterminator of fanaticism

for as far as our nation’s ships have sailed—

and that is dearer than the entire world!!

[Takes a breath.]

The laws of Nature and the laws of Rome

and, besides, the putrid morals of the country

[In a scientific tone.]

that for centuries have been

the legacy of Guelphs and Ghibellines:

The uncle woos the nephew’s bride—

He comes, he sees, he loves

Permit me to forego the ending.

Well then—and [smiling modestly] I am a man of many words

Here he is already—

[Pushes Karle, whom he pats on the back, toward the bed.]

[Exit Markwitz with an encouraging nod of the head.] [ . . . ]

Karle [Taking a big gulp of air]:

It is my most pressing desire.

Father [Remains self-controlled]:

Do not repeat this word if you don’t want to anger me.

Patients like you, my son, demand good care

And live under the watchful eye of their physician.

[A bell is heard.]

Karle [With self-possessed carelessness]:

My business went belly-up.

[Exit.]

Markwitz [Enters, stiffly]:

I am from Posen, Markwitz is my name.

As the delegate of all humanity of Posen I am coming here.

I am a Protestant. [Introducing himself] Markwitz.

Father [Suspicious]:

Markwitz?

Markwitz [Affirmative]:

I am a Protestant.

Father [Incredulous]:

You, a Protestant?

Markwitz [Smiling]:

Your faith, Sir, is also mine.

Father [Suppressing his doubts]:

Am I the first to know you from that side?

From that side, yes.

Father [Allusive]:

At the least the tone is new.

Notes

[Es ist erreicht was the name of the beard-polish that Kaiser Wilhelm used to get his mustache to bend upward. Later Es ist erreicht became synonymous with the shape of his beard. It literally translated to “It’s been achieved” or idiomatically in the twenty-first century, “Done.”—Trans.]

[Anstössig has three reinforcing meanings here: the dentalizing mode of speech (i.e., softening the hard consonants) typical of East European Jews; offensive and offending in a slightly sexual, unappetizing way; and also objectionable. Hence the word conveys both Markwitz’s mode of actively and consciously offending, as well as the outsider’s reaction to his way of being which was considered (by “proper” Germans in 1901) objectionable.—Trans.]

Credits

Max Reinhardt, from “Don Carlos an der Jahrhundertwende” [Don Carlos at the Turn of the Century], Schall und Rauch, vol. 1 (Berlin, 1901), pp. 81, 84–85, 97.

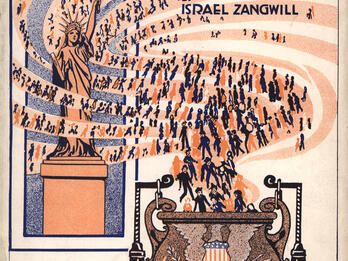

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 7.