Darkhe Tsiyon (Paths to Zion)

There are several ways to get to Jerusalem, as follows. One route is via Vienna, which is a point of departure for group travel to Constantinople, with traders going from Vienna to Ofen [Budapest], which is called Budin in Turkish. In Vienna, you can pay these traders to take you and your belongings as far as Ofen. It does not cost much, but you do need to obtain a pass from the emperor, which does not cost much either, since they are good people in the Jewish community of Vienna who are willing to go to a great deal of trouble in this matter and do whatever they can to help. You get from Vienna to Ofen by barge on the Danube. In Ofen, you are not allowed to disembark until word has been sent to the leaders of the Jewish community. These officials will then come and arrange for you to be permitted to enter the Jewish quarter. In Ofen you look for a traveling party—a “caravan.” Three people get together to hire a wagon, and they will have plenty of room for their possessions as well. The wagons are open-topped but with straw mats on the sides from protection from rain [puddles]. For a wagon like this as far as Belgrade, you pay six reichsthalers for three people. It is a journey of nine days. You pay another six thalers to continue from Belgrade to Sofia; six thalers again for three people to get from Sophia to Adrianople; and another six thalers to go from Adrianople to Constantinople. It is best to arrange for the wagon to go all the way to Constantinople while you are still in Ofen, because you cannot always be sure of finding a wagon along the way. If you prefer not to go via Constantinople, you can go from Adrianople to “Little Rhodes,” which is called Rodosto [Tekirdağ] in Turkish, and you pay four reichsthalers for three people to go from Adrianople to Rodosto.

Between Vienna and Sophia, Hungarian dinars are in use, five of which go for three kreutzers. There is also an “eighty Spanish kreutzers” coin, the same as eighty Polish groschen, which you can obtain for one reichsthaler all the way to Jerusalem. The lion thaler is not in circulation en route, as it is in Jerusalem. From Constantinople onward, throughout Turkey and even in Jerusalem, the reichsthaler does not have the same value that it does in these parts. Old Turkish dinars—in Poland they call them “old dreiers”—can be obtained at the rate of thirteen-and-one-half to the reichsthaler all the way to Jerusalem. In other words, one dreier is worth six aspers and one reichsthaler eighty aspers. Five new Bydgoszcz orts are exchangeable for one reichsthaler as far as Belgrade. Ducats of all varieties found along the way are worth ten kreutzers less than they are here, except Venetian ducats, known as zecchini, which are worth the same as here, provided that they are of full weight. In Jerusalem, one zecchino is worth two-and-one-third lion thalers. The realthaler is in circulation everywhere, even in Jerusalem, and is worth one reichsthaler. There is a silver coin in Jerusalem called the para, which is minted in Egypt, and if you go via the island of Rhodes, as I am about to describe, you can change one lion thaler for thirty-three paras there, whereas the value of one lion thaler in Jerusalem is thirty paras.

You would do well to buy Turkish-style travel garments in Ofen, where they are cheap. You should also try to get to Constantinople during the month of Av, since large vessels set sail from there as a flotilla each year at the beginning of Elul, and you can travel on one of these inexpensively and with greater safety from pirates. This, then, is one route, plus the relevant information on costs, clothing, and currency as far as Constantinople.

The other way is to go via Lvov, but you need to get there straight after Passover, because you set off from there with a great caravan of traders in the month of Iyar. You can find everything you need for the trip, whether foreign currency or clothing, in Lvov. You should reserve a place with the traders through to Constantinople; there are some good people who specialize in arranging this.

From Constantinople, there are two ways to get to Jerusalem. One way is by sea. With a few others, you hire a vessel in Constantinople or in Rodosto to go to Rhodes, for which you pay one-and-a-half thalers, known as a “Rhodosli,” per person. You should not take passage on a ship bound for Egypt, because Egypt is further than Jerusalem, and it will cost you a lot more to double back from Egypt to Jerusalem. Moreover, the route from Egypt to Jerusalem is very hard-going, whether by sea or land. In Rhodes, a large number of people, God preserve them, get together to hire a ship called a galley. Such a ship has twenty-five huge oars. If there is no wind to move the ship, then they can row. Such a ship is safe from—God forbid—pirates and unfavorable winds, because these ships do not venture far out to sea but stay close to the coast. There is just a day and a night on the Mediterranean when you can see only sky and water. If a ship of this type should list to one side, you have no need to be afraid because, when a good wind is blowing, these ships almost always list to one side. And may the Holy One blessed be He preserve you always from all sorrow and misfortune. Amen!

Credits

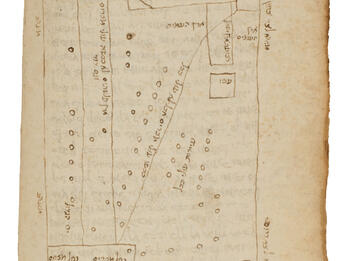

Moses Hirsh Porges, “Darkhe Tsiyon (Paths to Zion)” (manuscript, Jerusalem, 1615; first published Amsterdam or Prague, 1650). Republished in: Early Yiddish Texts, 1100–1750, ed. Jerold C. Frakes (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), pp. 655–656.

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 5.