Besamim rosh (Scent of a Bitter Spice)

Responsum 181

Now in regard to your inquiry as to my view on the question of the halakhic status of the odor of leavened substances on Passover, as there are some authorities who maintain that odor is included within the category of “something concrete” as well:

Response: The Sages stated that odor is not something concrete, insofar as a person is not liable for the consequences of any odor wafting out from his premises onto the public highway—so that it is comparable to mere respiration, which the Talmud maintains possesses no substantive reality. Indeed, if the issue were to be judged on the basis of large versus small quantities, then it would be feasible to incorporate it within the category of something of substance by virtue of the following reasoning: “If a single piece of bread is deemed to emit a minimal level of odor, which possesses a minimal amount of measurable mass, then a thousand loaves of bread would create odor and mass equivalent to the size of an olive [the volume held by the rabbis as rendering someone liable to a penalty were one to consume it on Passover]. Such a conclusion would be absurd, as it is clear that odor is not deemed to be something concrete; and even in regard to divers types of spices, the prime function of which is to produce pleasant odors, here likewise the odor produced is not deemed to be something of a substantive nature, as it is stated in chapter Ba-meh ishah (b. Shabbat 62): Said Rav Ada bar Ahavah: “That [ruling of R. Eliezer] effectively teaches us that one who on the Sabbath takes out less than the halakhically determined minimum quantity of food in a container into the public thoroughfare would be liable for taking out the container, even though he is not liable for taking out the food, since taking out a spice bundle that has no spice in it is comparable to taking out less than the minimum quantity of food in a container, as the aroma of the spice still remains.” Rav Ashi, however, declared: “Generally speaking, I would say to you that such a person should be exempt from liability, but in this instance the position is different, as there is no substance in it at all.” Thus we see that it is not regarded as something tangible—and although it would be feasible to argue that the minimal quantity inside the container is not treated as an independent entity, and is halakhically deemed to be nullified when it is measured against the size of the container, Rav Ashi did not say this, but merely that it does not constitute anything substantive; and even Rav Ada bar Ahavah does not require that it be treated as the equivalent of a real, substantive entity, since it has been stated in a mishnah that where there is no spice in a spice bundle, liability is incurred, but where there are spices contained therein, one would be exempt from liability. Hence we see that even a minimal quantity would suffice to satisfy the requirements of Rav Ada bar Ahavah, and how could he logically be heard to say that where the foodstuff does not contain a spice bundle, it is as though it did contain it? However, the Tosafists of blessed memory have stated that even a tiny quantity requires a minimum size/volume for liability to be incurred, and they have adduced proof from the statement made in this same chapter: “A woven item of any size whatsoever is susceptible to ritual impurity, and a decorative ornament of any size whatsoever, etc.” and additional proofs as well. Hence there are distinctions to be drawn between different kinds of minimal quantities, and indeed, when one analyzes the issue down to its finer points of detail, proof may be adduced from there. However, one could perhaps still invalidate such proof by contending that the phrase “There is something contained within it” is applicable only in instances where that thing can be handled physically as an independent entity, in its own right, such as the way in which women wear it, that being the definition of a decorative ornament. Nonetheless, there is a proof contained within the words of Rav Ashi, and proof may also be furnished from what Rav Ada says. However, this is not the appropriate place to elaborate further.

Responsum 259

In regard to a matter involving danger to life, we most certainly rely on the doctors, even where desecration of the Sabbath is concerned, and even in regard to cases where it is implicit from the text of the Talmud that this particular ailment does not involve danger, since we have perceived with our own eyes alterations within nature occurring in different eras insofar as all such matters are concerned. A number of phenomena exist the meaning of which we do not know how to fathom at all. And my teachers did not wish to leave it to people to rely, in the matter of diseases and remedies, on such as are mentioned in the Talmud, for they declared that the physical nature of the successive generations has changed. However, insofar as matters involving foods ritually unfit for consumption are concerned, they have retained the original halakhic status quo, so that a slaughtered animal with an adhesion of the lobes of the lungs to one another or to the chest is deemed unfit for consumption, yet one with an abscess is deemed fit, notwithstanding the fact that a doctor would maintain a contrary view. But we rely upon the doctor, and everyone, when sick, should place himself in the doctor’s hands, and ought not to suspect him of being incompetent. Indeed, I have seen no one who disputes this. I have personally witnessed a certain individual when he was a child, whose leg was broken at the top, close to the body, and the whole of the broken portion was severed from him by amputation, and the doctors made wooden supports for him, and he survived for a long time afterwards. Yet there is nothing remarkable about this, as the entire world has literally become altered—it is like a fresh world in all respects!

Credits

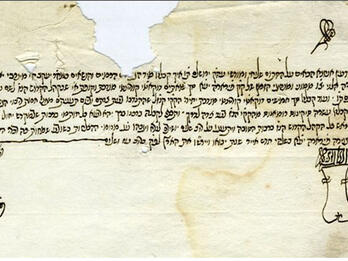

Saul ben Ẓevi Hirsch Levin Berlin, Sefer Sheʾelot u-teshuvot Beśamim Rosh, ed. Isaac Molina (Berlin: Bi-defus Ḥevrat Hinukh Neʻarim, 1793), 62v (responsum #181), 77v (responsum #259), https://hebrewbooks.org/1128.

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 6.