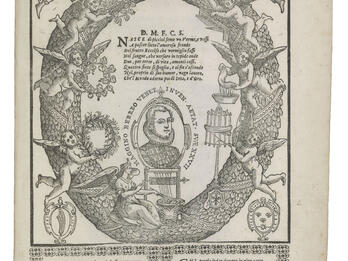

Ma‘aseh Tuvyah (The Story of Tuviah)

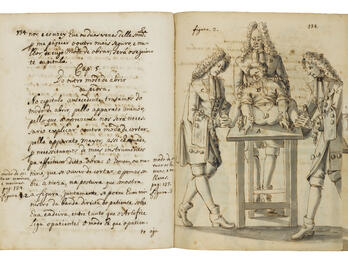

Ma‘aseh Tuvyah (The Work of Tuviah), by Tuviah ha-Kohen, an encyclopedic reference book on science, was first published in Venice in 1707. Three more editions were printed there in the eighteenth century and in other places over the next centuries. The volume is considered to be the most widely read and appreciated book on scientific and medical issues published in Hebrew. This illustration, from the section about medicine, is known as “the House of the Body” and is a visual allegory comparing the organs of the human body with the components of a house. Tuviah had both a yeshiva background and a medical degree. He utilized his university training in this book to create a most valuable work for his time, adding illustrations to help readers understand the text.

Chapter Two

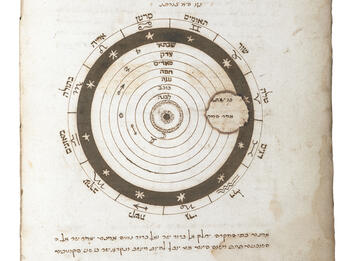

Various Arguments of the Astronomers Concerning the Matter of the Order of the Great Universe

In correctly understanding the truest theory, there were many opinions; but I will bring two principal arguments, and these are they: the first argument is that the earth is fixed at the center of the universe, and the heavens encompass it on each and every side. They eternally orbit around the earth, from east to west, and they move all of the stars along with them. This is the argument of Aristotle, Ptolemy, and Epicurus.

The second argument is that the heavens and stars do not move at all, but that the earth revolves and also turns around its center, from west to east, one revolution in twenty-four hours. This argument is old, and is from the school of the philosopher Pythagoras, and after him several others. Behold, this argument was renewed hundreds of years later by Copernicus; and in our generation, for many nations, this argument is set in their hearts.

The aforementioned Epicurus argued that all of the stars are based and set like nails in a wheel. When the wheel revolves, it moves all the stars along with it, from east to west.

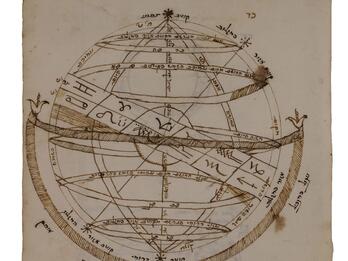

Ptolemy lived about two hundred years after the bones of Epicurus had disintegrated. He found a mistake in the length of the constellations, and argued that they are moved by a different sphere, which is called the Prime Mover. This is the daily sphere, which completes its revolution within 36,000 years, in accordance with the opinion of the astronomers.

The aforementioned Ptolemy sets the sphere of the earth as the center of the greater universe, and the moon revolves around it. He said that the moon has two motions, a yearly motion and a daily motion. Ptolemy further said that when the sphere moves with the first motion, it leads the moon to move from east to west, in a retrograde motion, while the moon itself moves from west to east on the circle of the ecliptic that passes through the plane of the poles of the circle of the zodiac. However, the moon does not precisely move in its own sphere; rather, in its sphere there is something like another nested small sphere or circle, and in the vernacular: epiciclo. It is like a stone set in a ring, which revolves, and the stone is sometimes above and sometimes below. After the sphere of the moon, he set the sphere of Mercury; and after that, Venus, and after that, the sun. After that comes Mars, and after that, Jupiter. The last one is Saturn. Above the seven aforementioned spheres, he set the sphere of the zodiac, in which are the stars, which have a motion different from the daily motion. This is around the ecliptic poles, from west to east. It completes one ecliptic rotation every hundred years. According to his calculations, they complete their movements in 36,000 years, as we have clarified above. Above the circle of the zodiac, which is the sphere of the fixed stars, according to his opinion, are the “sapphire” heavens [see Ezekiel 1:26; Exodus 24:10]. Above the sapphire heavens is the sphere of the first motion, i.e., the guide and mover of all of the spheres, with their stars. There are those who call this the “daily sphere.” [ . . . ]

Now, I will draw for you the order of the universe. The first sphere that moves is smooth and has no stars within it. It revolves around the earth in twenty-four hours. [ . . . ]

The aforementioned Copernicus set the sun at the center of the universe. That is to say that he changed the movement; the sphere of the wandering stars [i.e., planets] moves around the sun. With them is counted the earth, as one of the wandering stars. He says that the earth completes its revolution in one year, from west to east, in such a manner that its yearly movement does not delay its daily movement—i.e., its movement around the center within a twenty-four-hour period. The motion of the wandering stars is so straightforward that it is as if it were done with a pair of compasses and by way of a circle that inclines from the axis of the earth by twenty-two-and-a-half degrees.

Behold, according to the argument of Copernicus, the sun is in the center of the universe, and surrounding it is the sphere of Mercury, and after that is the sphere of Venus. Since they are close to it, their revolution is smaller, and is from west to east, and is completed before the end of the year. After this, he places the earth, and he says that it has three movements, i.e., a daily movement, a yearly movement, and a precessional movement. By way of this last movement, the difference in latitude—which was sensed from the days of Epicurus until now—becomes clear. It also becomes clear why it is that in our time, the poles of the earth are not at the same point at which they existed during the days of Epicurus. Hence, every day, the earth, according to his words, moves from the west to the east in a daily movement, and draws with it the moon that is dependent on it, in its orbit. [ . . . ] Afterwards is Mars, and then Jupiter. He continues in this order, etc. [ . . . ]

Tycho Brahe was a great astronomer and government minister in the Danish land, which is Denmark. He wrote a third argument concerning the system of the universe, which is midway between the two aforementioned systems. He agreed with the argument of Copernicus, but he wanted to make the earth the center of the sphere of the fixed stars. In order to clarify the movement of the heavens and the stars according to his desired argument, he accepts the argument of Ptolemy and arranges the earth at the center of the universe, standing still and at rest, without any movement. However, surrounding it, the existing stars revolve one revolution around it, from east to west, by way of the Prime Mover. In order to clarify the movement of the wandering stars [the planets] according to his desired argument, he inclines toward the opinion of Copernicus and says that the stars, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn all move from west to east, around the sun, and that the moon revolves around the earth, according to the opinion of Copernicus.

Credits

Tuviah ha-Kohen, “Various Arguments of the Astronomers Concerning the Matter of the Order of the Great Universe (Hebrew)” in: Tọviyah Kats, [Maʻaseh toviyah (The Story of Tuviah)] Hẹlek ̣rishon mi-Sefer ha-ʻOlamot, o, Maʻaseh Tọviyah (Venice: Bragadini, 1707/8, modern reprint, possibly New York, 1973/74), ch. 2., pp. 40–45.

Published in: The Posen Library of Jewish Culture and Civilization, vol. 5.

![12. [Image: MK12 Ma‘aseh Tuviah Frontispiece 1707] . Ma'aseh Tuviyah Engraving showing three main elements: on the left, a bearded man with his chest opened to reveal anatomical drawings of internal organs, including the heart and branching vessels; in the center, a vertical scroll filled with handwritten Hebrew text; and on the right, a cutaway view of a multi-story building with arched windows, a domed roof, and small figures inside.](/system/files/styles/prose_image_x2/private/2025-08/Posen5_blackandwhite283_color.jpg?itok=9XKhc5s1)